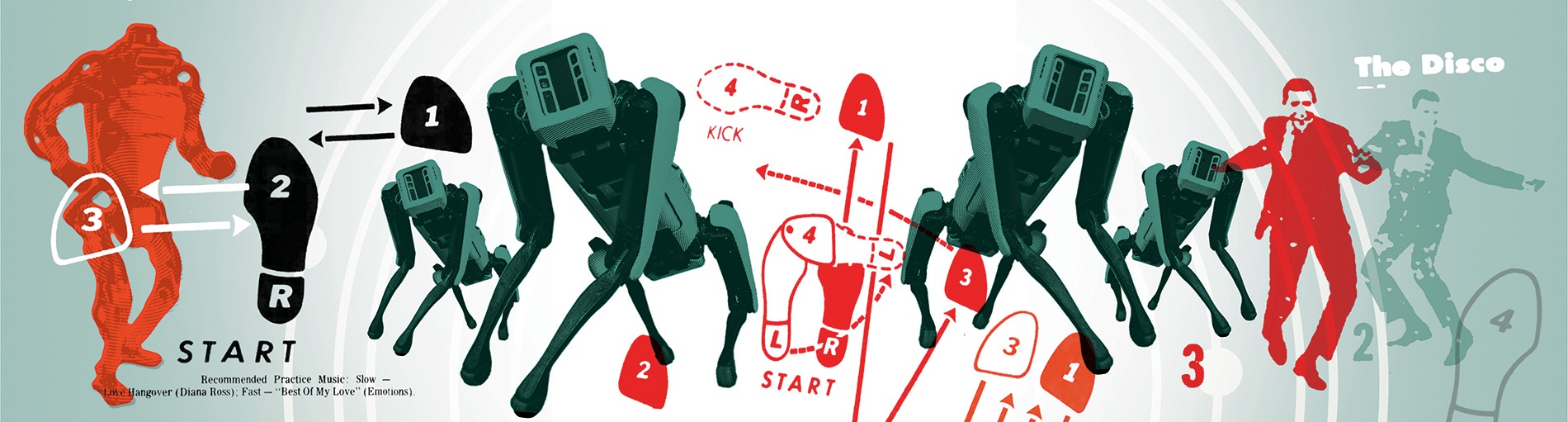

Making Robots Dance

At the intersection of choreography and engineering, a course looks at how robots move—and whether we’re programming them toward good or evil.

The Matrix. I, Robot. WALL-E. Ex Machina. For decades, countless films and television shows have asked: What would happen if humans created robots that were so smart they sought to replace their creators?

The question seems more eerily relevant every year, as scientists develop robots that are intelligent enough to drop fatal, precisely targeted bombs, carry on complex conversations, and solve difficult math problems. Enter Sydney Skybetter, a senior lecturer in theatre arts and performance studies at Brown University. An experienced choreographer with an interest in artificial intelligence, Skybetter has long explored what human movement and performance can teach people about responsible robotics. “I think artistic inquiry can help us understand and critique these emerging technologies—not only that, but it can also confer on these technologies a much-needed humanist core.”

In Spring 2022, Skybetter launched a course called Choreorobotics. Co-taught with computer science PhD candidate Eric Rosen and managed by Madeline Morningstar ’21, the course drew a diverse mix of students with experience in computer science, dance, theater, and engineering.

On the surface, the course’s objective was straightforward: Learn how to choreograph a 30-second dance using one of two pairs of Spot robots designed by the robotics company Boston Dynamics. Before students interacted with the hulking yellow and black devices, which resemble large dogs, Rosen spent a month teaching the class basic robotics concepts and terms and reviewing Spot’s safety manual. He also provided an overview of Choreographer, the software program that brings the robots to life.

Yet beneath the shiny spectacle of making the robots dance, there was a lot more to unpack. Through a mix of time spent in the dance studio, in the robotics lab, and in engaging discussions, students explored the kinds of questions they may confront in their careers: What are robots for, anyway? How can they improve peoples’ lives? And how can roboticists ensure their creations aren’t used to exploit or hurt people?

Ultimately, Skybetter says he hopes the course helps the next generation of engineers create emerging robotics and AI technologies that minimize harm and make a positive impact on society. “The subject of ethics and justice in technology development is incredibly urgent—it’s on fire,” Skybetter says. “I feel it’s my job to help students understand the implications of the technology we create now and in the future, because they are the future. I can’t resolve the issues we’re exploring, but my hope is that maybe they can.”

“When I tell people I’m double concentrating in computer science and theater,” says class member Navaiya Williams ’25, “they say, ‘What are you going to do with that?’ And to be honest, I didn’t know what to tell them—theater and CS always seemed so different and unrelated. But this class showed me avenues I didn’t know existed before.”

First, do no harm

Robotics is the perfect lodestar for conversations on dance, technology, and violence, Skybetter says, because it exists at the intersection of all three subjects. “Take drones, for example,” he says. “They look very cool when they fly together; they’re like synchronized swimmers. But the better these robots are at moving with precision and improvising when unpredictable things happen—in other words, the better they are at ‘dancing’—the easier it is to deploy them to inflict violence. And that leads to one of the governing questions of this course: How do we explore and understand these technologies while, to the extent that we can, not doing harm?”

That question has loomed for years for computer science concentrator Seiji Shaw ’22. He has been working with robots since childhood and, at Brown, has logged countless hours of research in the Intelligent Robot Lab. “I’ve spent a lot of time asking, ‘How do I make a robot move this way or that way?’” Shaw says. “Thinking about the ‘why’ of robotics—thinking about it from a humanities perspective—is something I hadn’t done before, and it’s something I always felt like I had to do.”

In the midst of a movement exercise, Skybetter asked Shaw, who had no prior dance experience, to direct a fellow student to raise and wave his hand without using the words “raise your hand” or “wave.” Shaw realized he could direct the movement step by step, like a choreographer or a programmer: Bend at the elbow, lift the forearm, lift the shoulder, open the palm, and finally bend the wrist back and forth. His directions worked, but his partner’s hand-waving movement looked, well, robotic—stiff, unsure, less warm than a human’s wave.

“The studio classes showed me how choreographers and roboticists often ask the same questions, but they’re getting at different things,” Shaw says. “They’re both creating sequences of movements, but the choreographer’s objective is to convey emotion or critique a social issue, and the engineer’s objective is to solve a problem. It’s made me wonder, what do we lose when we solve a problem without factoring emotion in? What if we combined human instinct with logic-based problem-solving to create technology that makes the world a better place?”