Build Your Own MD

Since Brown launched its medical school in 1972, its curriculum has been under construction, with students playing a key role in envisioning the new school and driving ongoing innovation. Now, at 50, the Warren Alpert Medical School has become a national leader in biomedical education, transforming healthcare in Rhode Island.

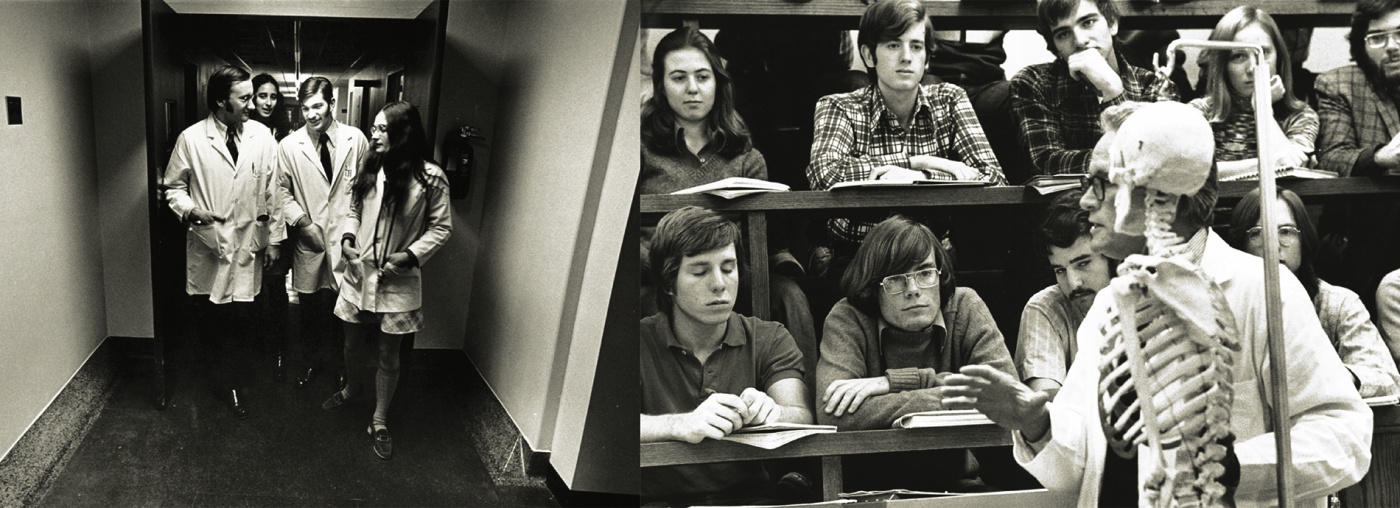

In the spring of 1968, Pardon R. Kenney ’72, ’75 MMSc, ’75 MD found himself sitting in a lounge in Keeney Quad before he’d even been accepted to Brown’s Special Program in Basic Medical Sciences. Established in 1963, the program consisted of four years of undergraduate liberal arts education followed by two years of graduate-level basic science; those who wanted to pursue medicine went on to do their clinical training elsewhere, often at Harvard. That day on campus, Kenney and about 40 other would-be “med-scis” listened as Pierre Galletti, the dean of biology and medicine, assured them that by the time they completed the program, Brown would have a full-fledged medical school.

“He made it sound pretty good,” says Kenney. “They were promoting the idea of producing Renaissance physicians, men and women who could do science but also had some element of the liberal arts about them.” He was accepted and matriculated that fall.

Indeed, the med program’s architects, including Stanley Aronson, chief of pathology at the Miriam Hospital, were envisioning a school whose mission would be to produce a new type of doctor: compassionate and well-trained, with a strong sense of social responsibility and “an understanding of, and sensitivity to, the broadest aspects of human experience in its personal and social dimensions”—the very ethos that animates Brown’s medical school today.

But in 1971, as Kenney entered his senior year, he still had no idea what his fate would be after graduating the following spring. Establishing a medical school at Brown was still a matter of intense debate and hardly a foregone conclusion.

The idea of reviving medical education at Brown (fun fact: the University had once offered medical instruction, from 1811 until 1827) had begun to take shape in the early 1960s. At the time, Rhode Island was one of few states without a medical school, so critically ill patients—not to mention insurance dollars—flowed over its borders into neighboring states. Proponents, including former Brown president Barnaby Keeney, touted the potential benefits to both the citizens and the economy of the Ocean State: a school would draw top-notch physicians and scientists to Rhode Island, and they in turn would bring better care, clinical trials, and federal research funding.

Opponents, on the other hand, shuddered at the idea of adding what many considered a “trade school” to a cherished liberal arts university-college. Many faculty voiced doubt or outright dissent, citing fears that Brown’s already scant resources would be drained by the costs and demands of such an undertaking. Even students opposed the idea, some vocally. In a November 17, 1971, letter to the editor in the Brown Daily Herald, one member of the class of 1974 warned that a medical school would bring about “the downfall of undergraduate education.” Referring to President Hornig and others who supported the idea, he wrote, “these men will have ruined Brown as we know it.”

In March 1972, after a long faculty meeting (which Kenney snuck into and was thrown out of, but not before hearing several arguments on both sides) the vote was 3 to 1 in favor of a school, and the Corporation approved it the following week. And so it was, six months later, that not one, but two classes of medical students began classes at Brown: Kenney’s ’75 MMS cohort, who were technically beginning their second year of medical studies; and the MD class of 1976, who were starting their first. Kenney remembers the relief he felt as he returned to campus: “Now we’re bona fide, second-year medical students at a bona fide medical school. We could concentrate on actually learning.”

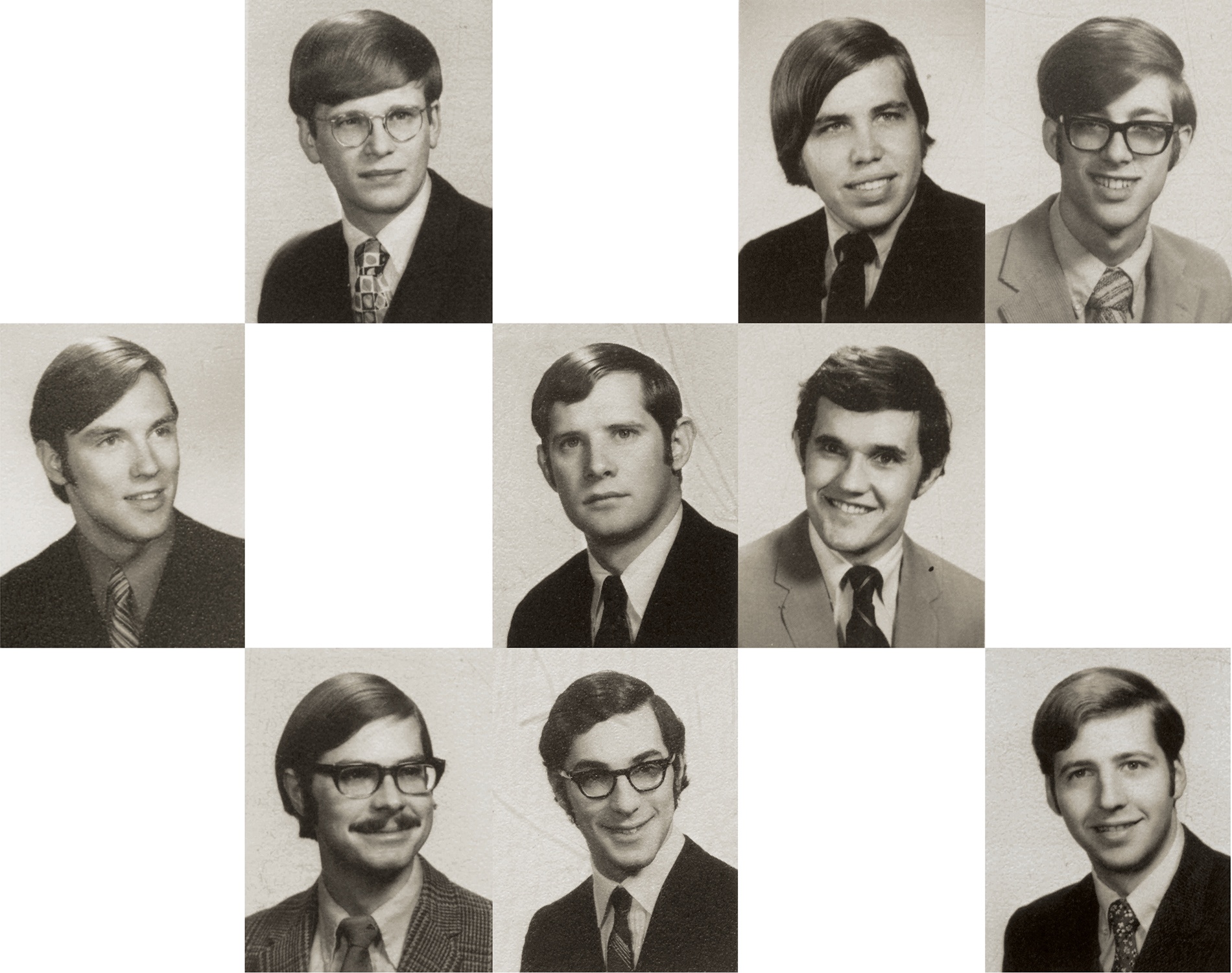

But another group of pioneers had preceded them in throwing their hats in the ring: a dozen daring students from the MMS class of ’71 (the majority of whom went on to medical school elsewhere) had already signed on to stay at Brown and take a chance on the yet-to-be-created clinical training programs in Rhode Island hospitals. They became known as the Charter 12.

Committing to a school-in-the-making was “exhilarating but also frightening,” according to Thomas Logan ’71, ’75 MD, one of the Charter 12. “We didn’t know what to expect, and neither did the powers that be.” Logan did enjoy being among the first students to take advantage of the brand-new Biomedical Center, which had opened in 1969 and featured an anatomy theater and lab located “in the belly of the beast.” Glenn Mitchell ’67, ’69 ScM, ’75 MD recalls that when the med scis went to lunch at Faunce House, “no one would sit near us” because they smelled of formaldehyde. But Logan says they loved being in the lab so much that “those of us with stronger stomachs brought our lunches in there.”

The Charter 12 were, as the BAM described them at the time, guinea pigs: they gave the physicians leading the nascent clinical training programs input and feedback after completing each new clerkship. “We told them what we saw as weaknesses, strengths, how to improve,” Logan says. “We were paving the way for those who came after.” Daniel Small ’71, ’73 MMSc, ’75 MD is proud of the students’ influence. When the faculty approached them about creating an honor society, for example, “we turned them down. We said, ‘No, we consider ourselves equals. No one is better than anyone else.’” Underscoring this esprit de corps, Logan says there was a designated note-taker in each class: “That way, everyone got notes every day. It was a cooperative effort. We saw this as a team approach.”

In a 1974 BAM story, “The Charter Twelve,” students described “few trials and some big plusses in this business of guinea-pigging.” For a start, there was having “a city-wide clinical teaching staff practically at one’s disposal.” Doctors “had never had medical students around,” Brent L. Davis ’71, ’75 MD explained. “They hadn’t had the opportunity yet to become contemptuous, or bored, or to know what we weren’t allowed to do. We had a pretty free hand to learn. It was an ideal situation.” The one drawback was just how concerned about the new students clinical teaching staff were. “They went overboard. Hog wild,” Edward W. Collins ’75 MD (who died in 1993) told the BAM. “Sometimes we were interrogated to death. ‘Is everything alright?’ It really got to the point that sometimes our biggest objection was, ‘Will you please stop asking us questions?’”

Students also served on every committee as the school came into being. Charter 12 member Paul von Oeyen ’71, ’75 MMSc, ’75 MD was one of four students who sat on the Medical Science Curriculum Committee. “There was a lot of debate about the top-heavy science requirements in the undergraduate years…which left little room for the humanities that might be important for a more holistic approach to medicine,” he says. “Thankfully those curricular changes were made and helped pave the way for the Program in Liberal Medical Education,” Brown’s signature eight-year continuum, formalized in 1985. (Von Oeyen had also, as a leader in the Medical Student Senate, earlier appeared on a local television show to make the case for a medical school in the state.)

Another Charter 12-er, Michael Shafer ’71, ’75 MD, says that Aronson, [beloved professor of medical science] Fred Barnes, and many of the faculty “treated us more like colleagues than naive kids. They gave us more respect and involvement than you would expect for the average student. They were so excited to have us involved and to be sharing all these great ideas that they were coming up with.”

“We were guinea pigs,” von Oeyen says, “but we were special guinea pigs.”

These aspiring physicians had chanced it, and their “gamble,” as Aronson said, paid off: in May 1975, donning newly designed regalia with a kelly-green accent, 13 women and 45 men—including the Charter 12—earned a Doctor of Medicine from Brown University’s freshly accredited medical program, one that many of them had helped build. Characteristically, the version of the Hippocratic Oath they took that day was one they had written themselves.

If Aronson later said that the members of the MD Class of ’75 “should be counted among the founders of the medical school,” it’s because they worked alongside faculty and deans to make it happen. “We encouraged our students to be open, to be skeptical, to challenge us, and they did.”

Ongoing influence

Nearly fifty years after the first class earned their MDs, the Warren Alpert Medical School’s alumni body is approaching 4,000, with some 140 students graduating each May. New life sciences and biomedical engineering centers are transforming the Jewelry District, where Brown has invested $225 million over the past decade. Residents of the Ocean State have benefited from Brown’s scientific and social contributions to addressing HIV/AIDS, opioid addiction, and COVID-19. More than half the doctors in the state are affiliated with the medical school, and half of those who complete their medical training at Brown remain in the state to practice. The ever-evolving curriculum has won awards for innovation. And students still have a say in where the medical school is headed.

Sarah Hsu ’17, ’22 ScM, ’22 MD was one of the students behind the med school’s recent focus on planetary health—the intersection of climate change and its health effects on individuals and communities. Hsu had long been interested in the topic but she didn’t find much about it in her classes.

“No one at the medical school was teaching it, and students had to look for information by themselves,” she says. So, in 2019, Hsu and other students met with Paul George ’01, ’05 MD, a medical education dean and then instructor in the med school’s innovative Primary Care–Population Medicine program, to request approval of a preclinical elective they had designed themselves. She recalls that George told them, “I’m not an expert in this, but I will sign your paperwork so you can start and we can all learn together.”

“The start of my journey in climate advocacy,” says Hsu, “was digging through 24 hours of emergency department waste to see what was going where.” This was research for her required thesis. Her dumpster dive into 1,600 pounds of trash revealed not only that many items were thrown away unused, but that every patient encounter in the Rhode Island Hospital emergency department resulted in more than four pounds of waste, most of it plastic. Her thesis was published in the Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: “Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health.”

The start of the Planetary Health elective led to a growing contingency of students and faculty interested in the subject and to the school’s joining others to pilot the Planetary Health Report Card, a nationwide student-led initiative that supports enhanced planetary health–related education, research, and outreach in medical schools. In 2021 when Brown received a B-, students brought the mediocre grade to the attention of senior administrators, who were open to finding ways to do better.

Jane Chen ’20, ’24 MD, and several other students drafted a proposal for teaching planetary health and submitted it to the Medical Curriculum Committee, which accepted it. Today members of the Planetary Health Integration Task Force, comprising student leaders and faculty mentors, are designing modules that will embed planetary health content into every block, from brain sciences to human reproduction, of their already dense four-year curriculum.

Chen describes seeing the changes she helped set in motion as “surreal.”

“Very few things get the blessing of a medical school curriculum committee to be integrated longitudinally, because there’s no time. Things that are given a green light are things deemed universally of importance,” says Senior Associate Dean for Biology and Curricular Affairs Katherine Smith, an ecologist who has long taught an undergraduate course on the topic. She and emergency medicine doc Kyle Denison Martin coteach the preclinical elective and have helped medical students develop a clerkship elective. The two serve as faculty mentors on the task force. Smith is emphatic that these changes came about because of students: “The students are that way at this medical school. They just do it.”

Now a resident in internal medicine at UCSF, Hsu says not all institutions are as receptive to change as Brown has been. “It makes a huge difference to have a supportive faculty, even if this is new to them, who are willing to give this a chance,” she says. “When there is student momentum, faculty back you up.”

Aaron Shapiro ’19 MD, today an internist working with underserved populations in Washington, D.C., also helped drive recent curricular change. Shapiro was outspoken about how the school could improve the way it teaches sexual health and LGBTQ+ patient care. When then–Senior Associate Dean for Medical Education Allan Tunkel invited him to be on a sexual health curriculum committee, Shapiro knew his opinions were valued. “The Office of Medical Education was the most responsive academic department I’ve ever engaged with,” he says, adding that he’s aware of other institutions where student activism is met with hostility.

Tunkel, who retired in the spring of 2022 and describes himself as “unflappable,” oversaw major educational changes during his tenure—many of them driven by societal upheavals, like those that gave rise to the Black Lives Matter movement and calls for diversity and inclusion. In response to a joint statement by a coalition of student groups calling for a more inclusive learning environment, required anti-racist training, and more accurate treatment of race in the curriculum, the medical school undertook a profound self-exam. In addition to making those changes, the school committed to recruiting and retaining faculty and students from groups underrepresented in medicine (see our April/May 2020 feature “Race Rx”).

“Students could say anything to me, and they did,” Tunkel says. “They taught me that sometimes you have to disrupt the system to make changes that are important.”

“In academic medicine, usually I’m the only person pushing for change,” says Patricia Poitevien-LeBlanc ’94, ’98 MD, senior associate dean for diversity, equity, and inclusion in the significantly expanded Office of Diversity and Multicultural Affairs. “Here, I’m surrounded by people who welcome change, which can be really uncomfortable. But they’re willing to do it for the students and, most importantly, for the patients.”

Jennifer Tsai ’14, ’19 MD, an emergency medicine resident at Yale, was one of the students who were instrumental in identifying racist content in, and helping reform, the curriculum. “Someone once advised me to be a part of institutions where there’s always construction going on, where there are always ‘cranes in the air,’” she says. “That describes Brown. It’s a very dynamic institution. It’s alive, and it’s changing.”

Additional reporting by Phoebe B. Hall

Sarah C. Baldwin ’87 is a freelance writer and the former editor of Brown Medicine magazine.