It’s Never Too Late

Manfred Steiner ’22 PhD pursues a childhood passion.

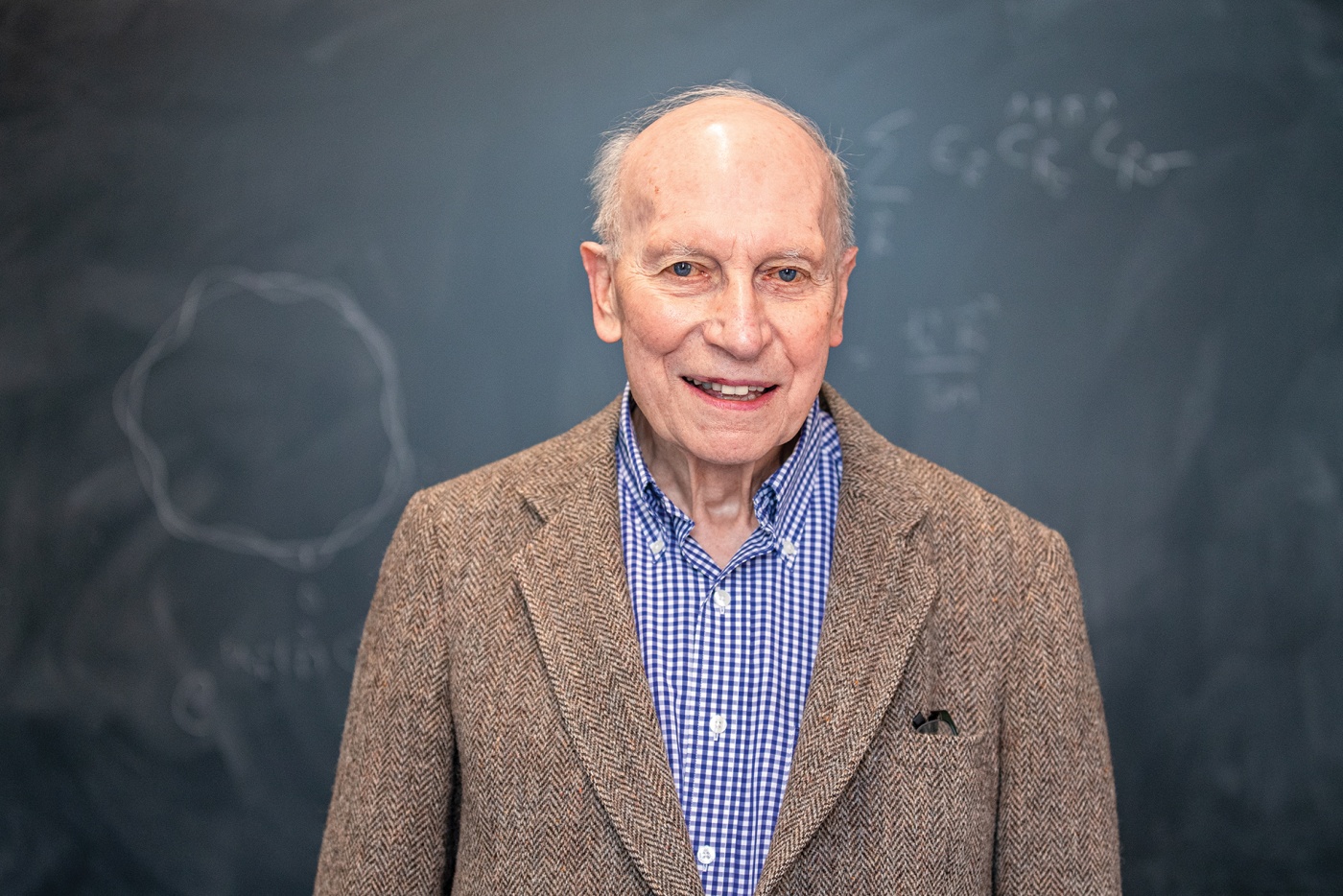

After emigrating from Austria when he was young, Manfred Steiner–a cheerful, soft-spoken man who is now 90 years old–spent 27 years as a professor at Brown’s medical school, where students used to say that “he speaks like the Terminator” because he never quite lost his accent.

He enjoyed his hematology research and he was good at it. But as a young man, he had wanted to be a physicist, and always, a persistent question remained: “I wonder what would have happened if I had studied physics?” Perhaps he would’ve been a success in that field, too.

When he retired, he decided to find out. Sitting at home without using his mind was “a nightmare,” Steiner says. So he enrolled at Brown as a special student and took one or two classes a semester.

His persistance paid off. In February, Manfred Steiner earned a PhD from Brown’s Department of Physics—more than 70 years after the field first captured his interest.

Steiner describes his childhood as “a terrible time.” Austria—and especially the city of Vienna, where he grew up—was heavily damaged during World War II. Steiner remembers the air raids. And he remembers his father, a university professor and plant pathologist who, unlike many of his colleagues, refused to join the Nazi party. Those who capitulated were allowed to stay home during the war, but Steiner’s father was forced to join the army, Steiner says, as “a punishment.” He did not survive.

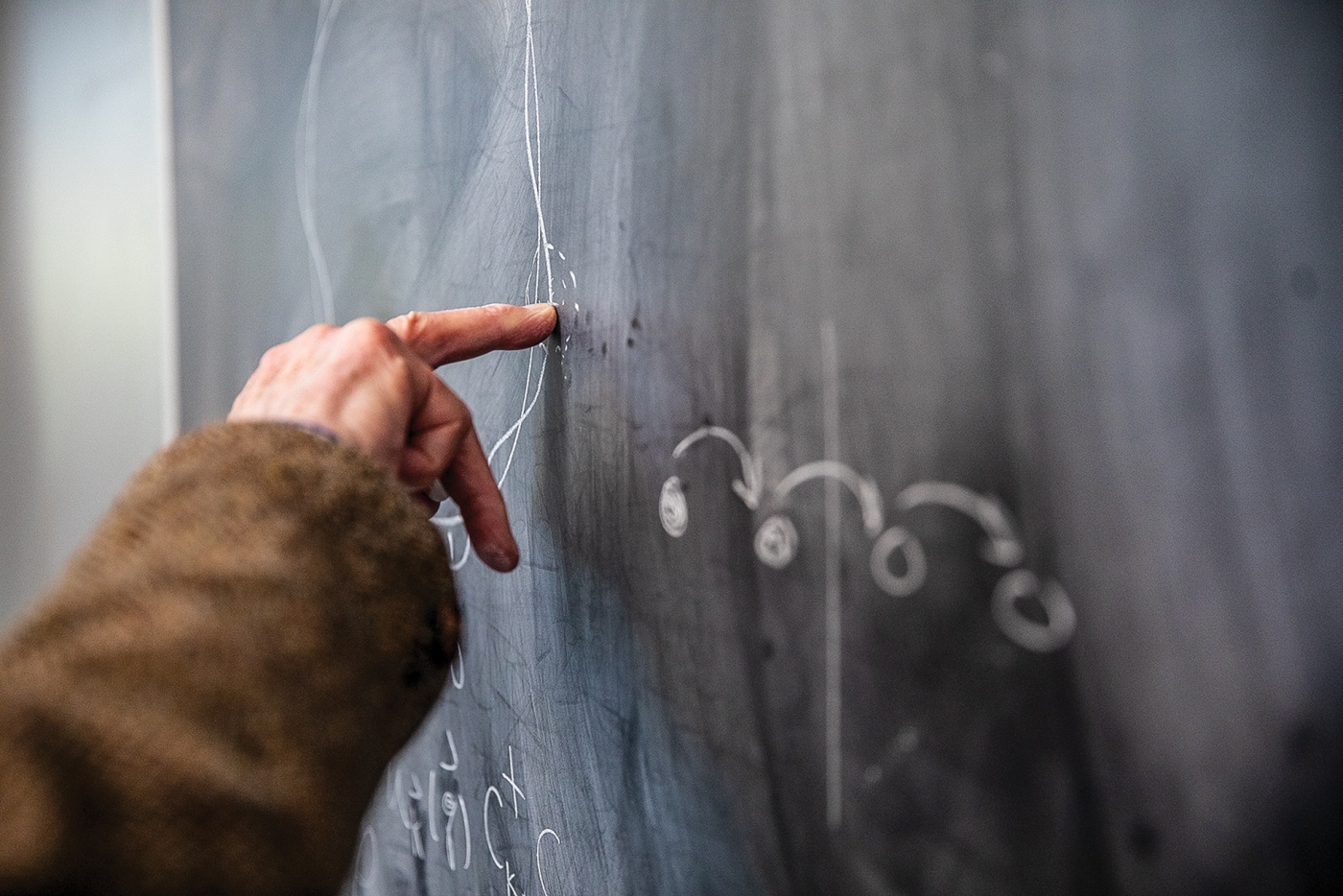

In high school, Steiner fell in love with physics. “It fascinated me because of the incredible precision,” he says. No matter how small or enormous something is–from a quark to the universe– “it’s still the same laws and you can prove it.”

But his mother and uncle argued that he should become a medical doctor, which his uncle said “would be more secure” than physics. “I followed the advice of my elders,” Steiner says.

Soon after graduating in 1955 with his medical degree from the University of Vienna, he moved to the United States. In contrast to Austria, America was “flourishing” and “progressive,” he says. There was more opportunity.

In his first week, he worked the night shift in the emergency room at Central Emergency Hospital, which was so close to the White House that someone told him he could see into Mamie Eisenhower’s kitchen. Interns like him would go out with the ambulance, and would make the momentous decision of whether or not to take each patient to the hospital.

He became chief resident and trained in hematology at George Washington University. Those hematologists recommended that he go to Boston or Salt Lake City, centers for the discipline. He was accepted at Tufts and started working with William Dameshek, a famous hematologist, chemotherapy pioneer, and fellow immigrant. But Steiner was worried he would have to go back to Austria. Dameshek helped Steiner get a permanent visa “as someone important to the United States.”

In D.C., a fellow doctor introduced his sister, Sheila, to Steiner. A fellow immigrant—her family was from Scotland—Sheila had trained to be an anesthesiologist. She and Steiner married in 1960 and have two children: a daughter who is a medical technician and a son who mediates healthcare mergers.

Jim Valles, a Brown physics professor, says that besides academic pursuits, Steiner’s greatest interests are Sheila and opera—the latter of which Steiner enjoys listening to while drinking single malt scotch.

“When I could realize this dream, it was enormous satisfaction. I did it, finally! So it’s not just for me another degree. It’s really the physics that I love.”

While in Boston, Steiner began studying at MIT and earned a PhD in biochemistry in 1967. Then a friend told him about Brown’s nascent Program in Medicine, where Steiner would go on to rise from assistant professor to full professor to director of hematology.

Word spread in the physics department about the unusual new student who had enrolled. He was 50 years older than most of his fellow students, but he was earnest, “conscientious,” “curious,” and asked good questions, says Valles.

Steiner had started his physics studies at MIT, but the commute was tiring for a man in his seventies. So he switched to Brown, where, after all, he knew the faculty were top notch.

The other students, Steiner says, “accepted me perfectly well.” The professors did, too.

“My brain maybe doesn’t work as fast as the young guys, but I still get eventually to the right answers,” he says, chuckling.

When he had questions, he would go to the graduate students’ office and someone would help him. In his acknowledgements section, he mentions a fellow student who helped him format his thesis.

At first, Steiner didn’t think he would pursue another PhD. But after finishing the graduate school requirements, he says, “I still felt mentally quite competent. And why not go for the cherry, for the big thing?”

His dissertation advisor, Brad Marston, says he “was initially reluctant to take him on.” Most theoretical physicists are young people. But it was clear that Steiner was devoted to his work and that his professional experience had prepared him for scientific research. Plus his story was “compelling.”

So Marston agreed, and helped Steiner pick a topic: bosonization. “I didn’t really have any expectation that he would ever finish,” Marston says. “And he clearly didn’t need a job afterward.”

Bosonization is in the theoretical realm of physics, which allowed Steiner to stay at home after a long career working in labs. “I never go to the library anymore because everything is online,” he says. His desk in his study at home is covered with stacks of articles from his research and several of the bookshelves are full of physics books.

In September, Steiner successfully defended his thesis, “Corrections to the Geometrical Interpretation of Bosonization.”

“This was always sort of in the subconscious,” he says, “but then, when I could realize this dream, it was enormous satisfaction. I did it, finally! So it’s not just for me another degree. It’s really the physics that I love.”

He’s an inspiration to his professors, too. Valles says, “His making the choice and sticking to it is incredibly affirming to those of us who love physics and have made that choice already.”

Next up for Steiner will be publishing an article that draws from a portion of his dissertation. After that, all he knows is that he wants to stay active. “I’m not looking for a paid job. I know I’m not in the running to be in competition with young people,” he says. “But if they want an older one who can do some research, I would like to be involved in physics in some way.”

Asked if he has considered teaching, Steiner says he’s past that. But he quickly adds that if anyone wants him to be a physics instructor, he’d be happy to help out. He likes students because they are curious—like him. “I like to be challenged by people,” he says. “That’s good. They don’t take everything for gospel truth. They question it.”