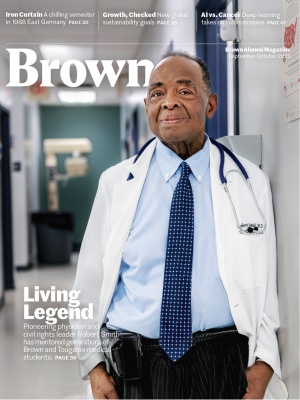

Through the Iron Curtain

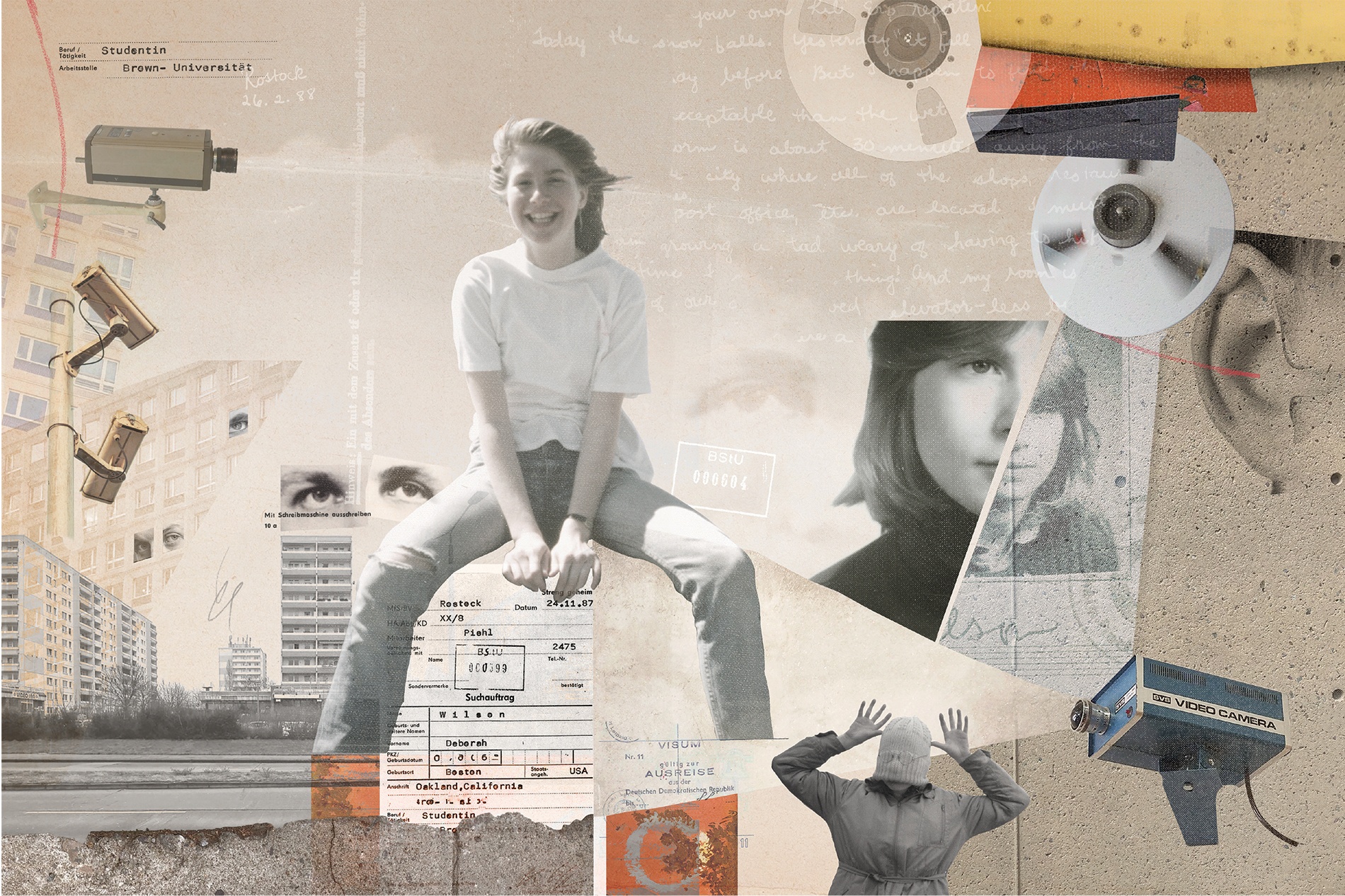

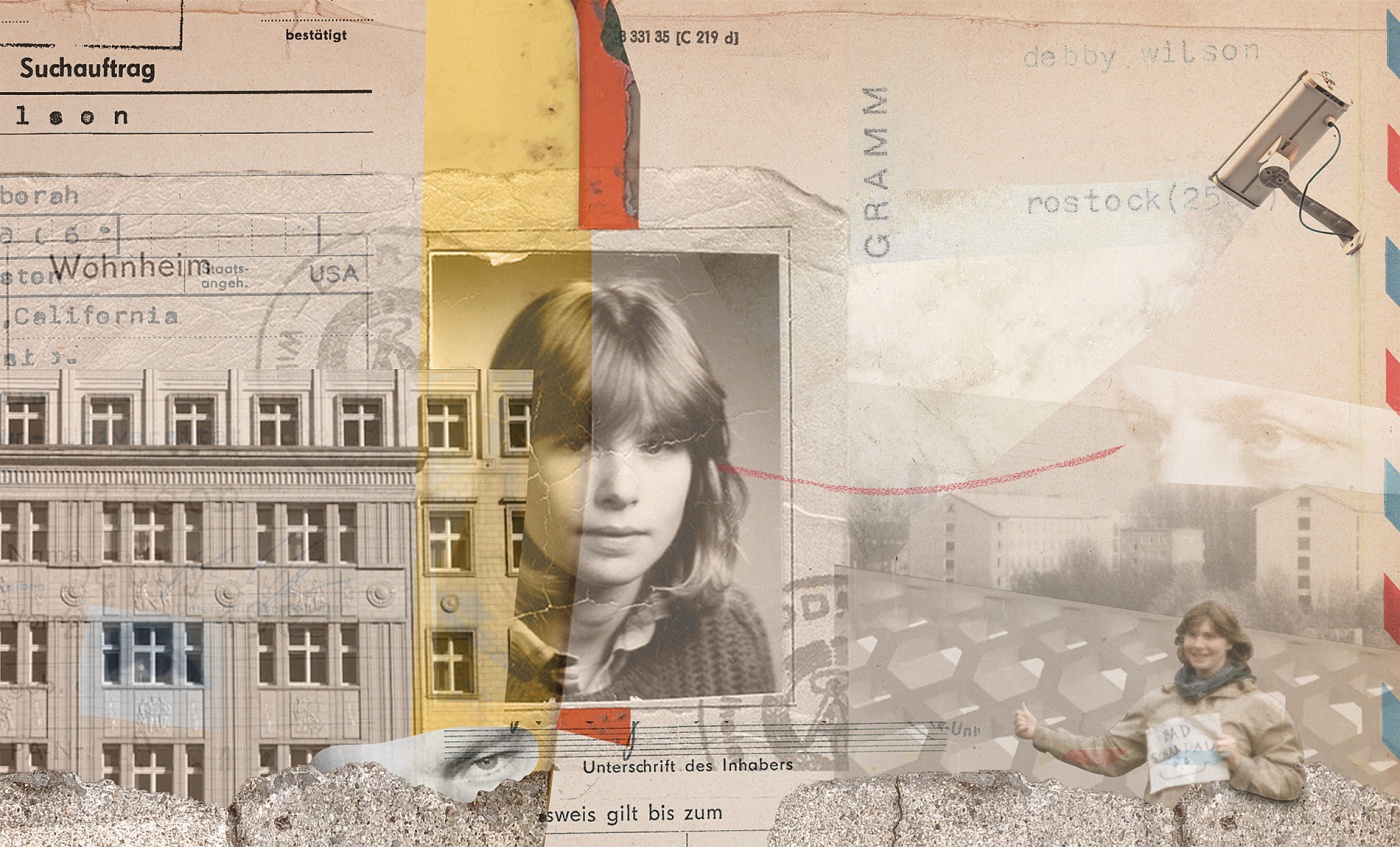

As Russia’s war on Ukraine gives a new generation a taste of what authoritarianism is all about, Debby (Wilson) Pattiz ’89 remembers her semester on the other side of the Berlin Wall.

Buckled into an aluminum tube, I hurtled away from everything I had ever known in the world—across a dark sky, over a dark ocean, and towards a dark curtain.

From West Berlin’s Tegel Airport, I made my way to the Friedrichstraße border crossing into East Berlin. It was February 1988 and the unsmiling East German passport control agent was unsure what to make of the American college student and her bulging backpack with a teddy bear head poking out. My papers were in order, however, so I was liberated from the narrow holding booth by a sequence of sounds: the rat-a-tat of an industrial date-stamper, the buzz of an electric lock release, the boom-boom of my hammering heart. After the portal through the Iron Curtain clicked closed behind me, I descended along the worn linoleum of the flickering pedestrian tunnel that passed under the Wall—the frontline of the Cold War. Emerging into the gray glare of the twentieth century’s second German dictatorship, I wondered: Would I discover a common humanity with Communists?

On the elevated train platform in East Berlin, I rendezvoused with three other Brown students bound for Rostock. In Rostock, we were met by the frantic smile of a mustachioed man and the trademark East-Germany-in-winter smell of burning brown coal, which nipped at my taste buds and stung my eyes.

The air looked different too. Coal smoke had painted the sky sepia, making me feel as if I’d stepped into an old photograph—and in some ways, I had.

My sojourn in East Germany was inspired not by fervent ideology but by a need to know if the storyline permeating my childhood was true. Growing up in America during the Cold War, I had difficulty imagining that people living in the Soviet Bloc could be happy. What I had no difficulty imagining was that “the Commies” might obliterate the world with nuclear warheads at any moment. Studying in West Germany during high school had also made me curious: how different could the people living in the other half of a divided nation possibly be? When the chance to see for myself was presented by Brown University’s unprecedented exchange (see sidebar below), I took it.

Socialism in action My first weeks in the lovely port city of Rostock were happy and I felt relieved. Time itself seemed to pass more slowly. The people seemed. . . well, normal. I was charmed by the children’s pointy knit hats, the banners everywhere promoting world peace instead of McDonald’s hamburgers, and the startling Lebensfreude (Joy of Life) fountain featuring a frolicking family of naked people accompanied, inexplicably, by various sea creatures and a warthog cavorting on its back.

“Would I discover a common humanity with Communists?”

Having grown up in a rough neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago, an alien feeling of security also amazed me. People weren’t worrying about crime, hunger, poverty, or drugs. “Those evils come from capitalism,” they told me. I walk home on a dark street at midnight.

Another difference was an unfamiliar something in my peers that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. They seemed to walk along the street and into their futures with an assuredness that was unknown to me. I crunched through the snow behind Andrea, an East German girl who sported a puffy green winter parka and was speaking with animation about her fiancé and their wedding plans, waving her engagement-ring-emblazoned hand in the crisp air. Although we were about the same age, Andrea had few questions about what her life had in store. I, on the other hand, had no clear picture of a career. No fixed sense of what country I would live in, let alone which city. Marriage and children? Definitely, but first I wanted to soak up the world, soak up different experiences, not be tied down to one pathway. My options were endless, but also overwhelming.

Eavesdropping on Andrea’s contented description of her future, I felt seduced by her puffy jacket and all it stood for. What would it feel like to know—and not merely wonder—how my life would unfold? The boundless independent life stretching out before me abruptly lost its shimmer. Perhaps endless options were not good for the psyche. What if someone could plan my life—and make it good enough, exchanging the thrill of possibility for the guarantee of security? I tasted the allure of what a socialist system offered that my own could not.

Dark lessons I also took a deep dive into the pedestrian ways that regular, good people accede to the demands of dictatorships. On an overnight trip to Weimar with a group of East Germany’s future history teachers that Mickey Butts ’90, Gillian Silverman ’89, and I were invited to join, I encountered subtle lessons in the architecture of oppression that have taken me three decades to process.

The first lesson related to conformity and surveillance. After spending the night in single-sex, bunk bed-filled barracks in Weimar, we rose early and filed off to the dormitory bathroom—together. Gillian and I looked around for the showers. Instead, our female companions had formed an orderly line behind a row of washbasins in the communal lavatory. When her turn came, each girl approached a vacant sink where she performed a well-rehearsed sequence in plain view of those behind her in line. Whipping off nightshirt and underpants, each soaped up and went for a vigorous washcloth bath, scrubbing not only under here and here, but down there and there.

I accepted that my letters and telegrams were intercepted, that registration with the police in any city I visited was mandatory, that a clandestine “minder” had been assigned to report on my activities. But surveillance of personal hygiene violated a boundary of privacy I was unprepared to surrender.

Another lesson was on misinformation and silence. Later that morning, our troupe of Brown students and the future history teachers of East Germany entered a wintry forest, tromping single-file through twinkling snow. The tranquil woods reminded me of my grandparents’ rustic summer cottage on Beech Hill Pond in Maine. Then it hit me. This trail did not lead through a beech tree forest; it led through the beech tree forest. This was Buchenwald (literally, “beech forest”). As if a World War II newsreel were being projected onto the dappled path, ghosts of prisoners appeared, stumbling along beside us. Marching out of the woods, we beheld the concentration camp guardhouse and Buchenwald’s infamous gate with the words “Jedem das Seine” in iron lettering across the top. “To each his own” in idiomatic German . . . or, in Nazi rhetoric, “Everyone gets what he deserves.”

“Coal smoke had painted the sky sepia, making me feel as if I’d stepped into an old photograph.”

Although the West Germans I’d met during my high school exchange in 1984 did not speak about the atrocities of Hitler’s Holocaust, an ineradicable shame had branded them nonetheless. I presumed that shared ethnic culpability would provide a rare instance of unity between the two Germanies. I presumed wrong. Gillian and I entered a building housing the Buchenwald memorial. An exhibit portraying the fate of German communists at the hands of the Nazis caught my eye. I had never heard about that before. How could history here diverge so significantly from what I had been taught at home? Pondering this paradox, I sidled over to Gillian. The two of us searched for the German word Jude (Jew) among the tens of thousands of words inscribed at the Buchenwald memorial. We did not find it. Not once.

Not only had the Jews of Germany and beyond been stripped of livelihoods, rights, homes, possessions, protections, and lives, but in official East German history they had also been stripped of the justice of remembrance. In my journal entry from March 5, 1988, I wrote, “Buchenwald revealed the extent to which thought and history can be controlled.”

Without access to other sides of the story, what would trigger regular, good people to ask themselves the kinds of questions I found myself considering: Would I oppose policies that benefitted my family but strip others of opportunity, civil rights, property, liberty, or life? Would I endanger my family to help others being persecuted for their beliefs or race? Would I speak out against people I loved or admired—feared or revered—if their actions were unethical?

Goodbye means forever After the first cold months, sunnier days and warmer weather brought fresh vegetables to Rostock and my journal celebrates their appearance: scallions, a cucumber, radishes, lettuce. Winter produce had been literally limited to potatoes, cabbage, carrots, apples, green un-juicy oranges from Cuba, and onions.

I embarked on adventures with Anneli, my roommate and dearest friend. We hitchhiked to the Elbsandstein Mountains on the southern border with Czechoslovakia and found ourselves illegally smuggled onto an East Germany military base by a delivery truck that unwittingly gave a lift to a forbidden Staatsfeind (enemy of the state). We paddled boats in the lake surrounding the Schwerin Palace, hiked on the Baltic Sea island of Hiddensee, played Rippel-Tippel (a drinking game that involved marking your face with a scorched cork), and talked until all hours of the night.

And we sat on the beach and watched the ferry as it departed regularly for Denmark and wondered: What kind of world is this, where one of us can get on that ferry any day she chooses, but the other never can?

The day came for my train into Poland. I loved my friends and did not want to leave them. “They cannot visit me. Ever,” I wrote to my family.

I realized that my relationship to my own country had changed as well. I understood that I could never return to the person I was before.

Before I departed, I wrote to a friend from Brown who was considering coming to East Germany: “I will help you pack, and I will write you and send peanut butter—but you must come! You will love it and you will hate it. Oh, will you hate it! But, oh, will you love it.”

Although I left Rostock in mid-June 1988, Rostock never left me.

Adapted from My Cold War Cold Case: Memoir of a Mystery by an American in East Germany by Debby Pattiz ’89. In 1988 a young East German acquaintance told Pattiz about her ties to the underground resistance, then abruptly disappeared. Three decades later, Pattiz returned to Europe to unravel the mystery of this vanished girl from a disappeared country. Contact Pattiz or learn more about her project and memoir, for which she is seeking representation, at debbypattiz.com.