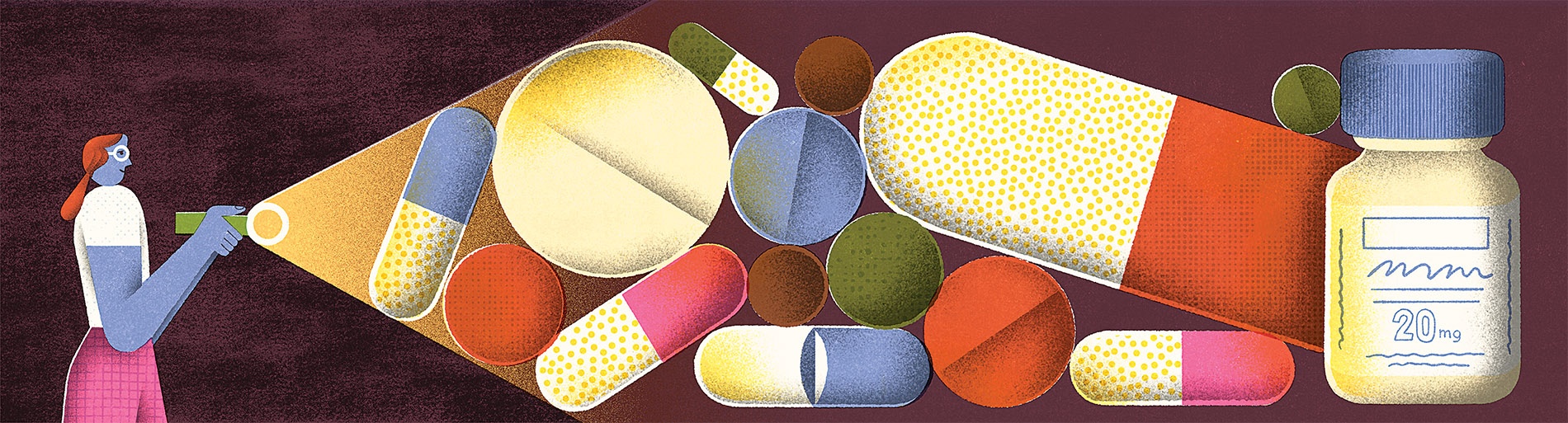

Rhode Island’s Opioid Crisis, Exposed

A data-driven dive into how, even in the smallest state, billions of addictive pills were manufactured, prescribed, and abused.

In the early months of the pandemic, Pulitzer Prize–winning journalism professor Tracy Breton spent several days at Rhode Island’s Judicial Records Center going through scores of court records involving Christopher Huntington, a doctor who killed himself after his license was suspended for overprescribing opioids. Because of the pandemic, Brown students were not allowed to do their own research at the JRC, but Breton, who covered the courts in Rhode Island for 40 years, was given a small room where she “barricaded” herself for several days.

By the time she was done, she had filled two large boxes with old court documents. Then she delivered them to Li Goldstein ’22, who had never tackled such an ambitious public records story before. Breton told her to put the records into chronological order, which Goldstein says took months, but made it easier to organize the story, prepared her for interviews, and increased the trust her subjects placed in her because they could see that she knew the story well.

Huntington died in 2013, but his story—like many of the 32 other stories that made up the Rhode Island Opioid Data Journalism Project—had never been covered in-depth. “So many local papers are cutting staffs or going under,” says Breton. “And there’s just this real lack of local investigative reporting.” The project helps to “fill the gap.” At the same time, Breton felt that the stories had to be data-driven to combat hostility towards journalists fueled by Donald Trump.

Her students worked with the students of Ugur Cetintemel, a computer science professor who teaches a class called CS for Social Change. Cetintemel assigned a group of students to work on the project, and the CS department also provided $2,000 to buy raw data from the state judiciary.

The collaboration produced stories like an article about trends in narcotics prosecution over 30 years (by Lena Renshaw ’20, Colleen Cronin ’21, Gaya Gupta ’23, and Marina Hunt ’21), an analysis of where people were overdosing and how overdoses could be broken down by demographics (by Olivia George ’22, Marina Hunt ’21, and Colleen Cronin ’21), an examination of where prescriptions were being written and filled in high volume (by Olivia George ’22 and Hal Triedman ’20), and a look at two subsidiaries of Purdue Pharma, which were located in Rhode Island and made billions of opioid doses.

Hal Triedman’s story about Purdue’s Rhode Island companies—which have been so secretive that many neighbors did not even know what they were producing—and the analysis of overdose locations has already been published by The Public’s Radio. All the stories are posted on the publicly available thepublicsradio.org and more are planned for the future.

The Providence Sunday Journal also published a story by Marina Hunt ’21—on the front page, above the fold—about the first person in Rhode Island to be sentenced under Kristen’s Law, which allows dealers who sell drugs that lead to fatal overdoses to receive sentences up to life in prison.

COVID-19 made in-person journalism difficult, but Hunt still had meaningful reporting experiences. She forged a relationship with the Providence police officer in charge of records who gave her a week of police reports for a story about policing drug crimes. And she talked to those affected by the opioid epidemic, including an older woman who had rented the basement apartment of her house to a drug dealer who did not pay rent, who held a gun to her head, and whom she was unable to evict. Hunt says she had thought her story would be “very true crime and action-packed,” but this woman “brought humanity to it.”

Part of the goal of the project is to humanize the epidemic. Goldstein wants people to understand the magnitude of the state’s problem and hopes the reporting will “shed light on this interconnected web of players and stakeholders that allowed the drugs to proliferate —and also honor the people who are doing the really important work of stopping the epidemic in its tracks, caring for the survivors, and advocating for sensible drug-use policy and for rehabilitation.”

In addition, Hunt and Breton say, they want the project to help remove the stigma of opioid use. Breton hopes it will lead to more funding for people who are dealing with addiction and “that people will be shocked at the number of pills and raw opioid material that was both manufactured in this state and distributed in this state.”

Breton retired at the end of this academic year after 25 years teaching journalism at Brown and mentoring students who have gone on to have successful reporting careers (see story, p. 12). She’s proud of her students and their work. Some, she said, “graduated in 2020, but they kept working on the stories, even after they started new jobs, because they were so committed to the project.”