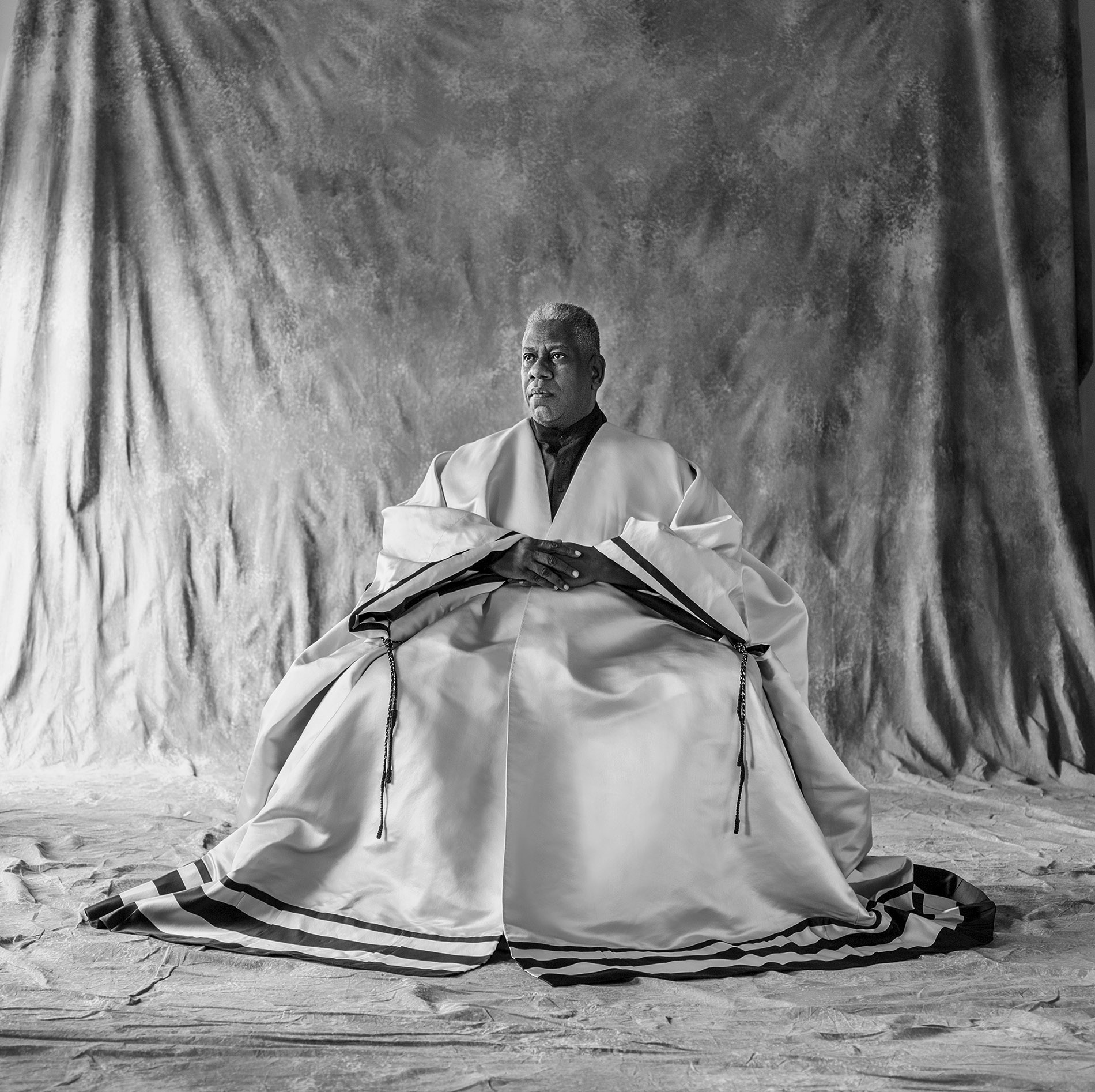

When André Leon Talley ’73 AM died at age 73 on January 18 at his home in White Plains, New York, the media focused on the larger-than-life, longtime Vogue creative director’s near-half-century at the glittering peak of the fashion industry: his long and close ties to top designers including Karl Lagerfeld, Tom Ford, and Diane von Furstenberg; his fashion mentorship to Michelle Obama and his promotion of Naomi Campbell and other models of color; and, perhaps most famously, his decades-long bond and more recent break with longtime Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour.

But before Talley decamped in the mid-’70s to New York City to labor in “the chiffon trenches” of fashion, a term he used for the title of his bestselling 2020 memoir, he was a graduate student in French literature at Brown for more than three years. He arrived on College Hill after having studied French at the historically Black North Carolina Central University, in the same state where he grew up, raised by his grandmother and in the Black church. His scholarship at Brown would form an important part of his encyclopedic knowledge of history, literature, art, and fashion —the very reason Wintour, in the 2018 documentary The Gospel According to André, says she hired him at Vogue.

“Brown was a liberating experience for me,” Talley told the BAM in a 2020 interview to discuss The Chiffon Trenches. “I met sophisticated people and I was rather sophisticated in my own education, so I adapted easily and was surrounded by Black best friends.” His master’s thesis was on the influence of Black women in the writings of Baudelaire and Flaubert and the paintings of Delacroix.

One of those friends was Dr. Janis Mayes ’73 AM, ’75 PhD, emeritus professor of African American studies at Syracuse University, who remembers meeting Talley in the Grad Center upon arrival for the same French studies program as he.

“He was so kind and friendly and really well dressed, and he lived in the most beautiful, elegant dorm room with fabrics on the walls,” she recalls. “He read everything and his interests extended from painting to fashion to politics. He was always at the Black Baptist church in Providence on Sunday, impeccably dressed.”

Talley and Mayes traveled to Paris together on school breaks and, even after Talley left academia for the New York fashion world, stayed confidantes for life—talking, says Mayes, as recently as a day before his death. “His values never changed,” she says. “He believed in goodness, in manners, and accepting people for who they are. He had a very strong ethic of right and wrong and he believed in family and friendship.”

Mayes says that Talley would sometimes express frustration with the racism and other cruelties of the fashion world, particularly in recent years, after he was let go from Vogue—and, in his account, frozen out by Wintour. “But he never saw himself as a victim,” she says. “He recognized the racism in the fashion world but tried to do something about it by promoting models” of color. “He did his activism from within the industry.”

He also threw himself into mentoring young talent. In the past few decades, not only did he develop a close relationship with the Savannah College of Art and Design, he also came back to Brown in spring 2019 to screen and discuss the documentary about him. Wearing one of his voluminous signature muumuus, he turned his keen fashion eye on the audience, asking various students to stand and show off their outfits.

“He interviewed us,” recalls Sasha Pinto ’21, who started Brown Fashion Week and led the group Fashion@Brown. Then Talley invited several of the students in the crowd to a lavish “voguing” ball in New York City benefiting the LGBTQ youth of color nonprofit FIERCE and featuring celebs like Campbell and Wendy Williams. Talley, in a royal red robe, watched the proceedings from a gold throne on the stage, demanding that attendees twirl before him to show off their looks.

“They called us André’s Talley-ettes that night,” recalls attendee Jack Nelson ’21. “We really didn’t know what to expect, but André was super-charismatic and over the top. I dress opulently now and I owe a lot of that to him.”

Mayes recalls a favorite memory of Talley from their Brown days. He told her and his other Black female friends that they had to attend church with him. “He told us to wear our Sunday best.” The group arrived slightly late. “We should have slid into a pew in the back, but instead he leads us down the aisle to the second pew. The minister looked up and said, ‘Let the church say amen!’”