At the Fork of the Stream

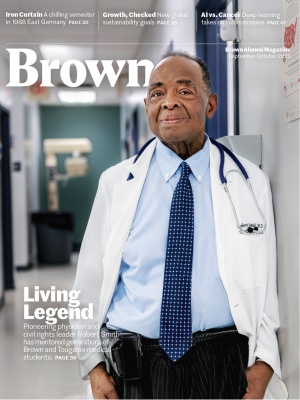

In 1964, at the height of the battle to end segregation, Brown entered into a partnership with Tougaloo, a historically Black college in Jackson, Mississippi. From that first year to today, Brown students have been mentored by beloved physician, civil rights leader, and “living legend” Dr. Robert Smith.

In 1985, Emma Simmons ’91 MD, ’06 MPH, then a 16-year-old high school junior, needed a physical examination to participate in a summer program at Tougaloo College. Simmons had never liked seeing doctors, who had always treated her with a clinical reserve, aloof in white robes, making her feel “like a pariah” when they touched her.

But in the clinic she met Dr. Robert Smith, who since 1963 has headed the Mississippi Family Health Center (now known as Central Mississippi Health Services), the state’s first multispecialty clinic providing care regardless of a patient’s ability to pay, transforming access to medical care for communities of color in Mississippi.

“He talked to me, he asked me questions about my life,” Simmons says. “That was powerful. He was my model of what it means to be a doctor.”

Simmons entered Tougaloo, a historically Black college in Jackson, Mississippi, on the pre-med track, then was selected to study medicine as a graduate student through the Brown-Tougaloo partnership, before also going into community health. Today, she serves as a senior associate dean of student affairs at the University of California Riverside School of Medicine.

“I am a doctor today because of Dr. Bob,” she says. “The biggest lesson that I learned from him is that you can be yourself and be part of a community. And be a good doctor.”

Simmons is one of thousands of patients whose life was influenced by Smith, who spent decades on the frontlines as an activist in the civil rights movement. “Dr. Bob” provided medical services to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s Selma to Montgomery march and became a civil rights leader within the Southern medical establishment, combating racial inequity in healthcare. Smith also mentored decades of future Brown and Tougaloo physicians, providing firsthand exposure to conditions on the ground in Mississippi.

“He genuinely respected each patient. To see that model when you’re a young physician in training is really important.”

Physician David Egilman ’74, ’78 MD, who is white, recalls that to work in Smith’s clinic in 1978, he needed to apply for a Mississippi medical license and interview with officials from the state board. When they found out Egilman planned to work with Smith they were shocked. “It was the first integrated private practice in Mississippi,” Egilman says the board told him.

He remembers the de facto segregation still in practice around the state. “I don’t think there was a sign but everybody knew that the back door was for African Americans and the front door was for whites,” Egilman says.

Simmons’s husband, Scott Allen ’91 MD—who is white, grew up in Connecticut, and “knew nothing of Mississippi” by his own admission—spent several weeks following Smith on his rotation in Jackson. Smith did whirlwind visits to three hospitals twice a day. To help Allen keep up, Smith rented him a car for the month and connected him with a local family to stay with.

At Smith’s clinic, there were no appointments. Patients were assigned and seen based on the order they walked in. While there were other excellent doctors in the clinic, Allen recalls some patients were willing to wait all day to meet with Smith.

“He genuinely cared for each patient,” Allen says. “He genuinely respected each patient. To see that model when you’re a young physician in training is really important.”

Oppression and inspiration

Smith’s grandfather, born in slavery, had to flee his home in Charleston, Mississippi, after getting into a fight with his white boss. In the family lore, his grandfather tried to hitchhike the Illinois Central Railroad track running north but accidentally got on a southern bound train. He ended up deeper in Mississippi, in a small town called Terry.

Smith’s grandfather later managed to buy land in Terry, building a farm producing grits and molasses that has now been in the family for five generations. Smith grew up there, the third youngest of 12.

Inspired by a book of famous Black Americans he received, Smith’s first passion was the piano, but he says he lacked talent. Yet he found himself captivated by another figure in the book, Charles Drew, who discovered how to preserve and store blood plasma.

A white Jewish physician who hunted around the area learned of Smith’s interest and gave him some old medical textbooks when Smith was still a young teenager. Smith says he read them all, skipping grades and propelling himself through school.

In the early 1950s, there were very few high-quality liberal arts colleges available for Black students, but Tougaloo was one of them, offering a healthcare track. The college also offered space for students like Smith to discuss politics, social issues, and activism. He remembers going, as a student, to view the body of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old who was kidnapped, tortured, and lynched for allegedly flirting with a white woman. He also participated in an unofficial “intercollegiate council” offering discussions between Tougaloo students and Millsaps, a white liberal arts college.

“When it became public, after my time, the group had to dissolve,” Smith recalled in an oral history for the Civil Rights Movement archive. “As Mississippi found out about anything that suggested openness or diversity or integration, then it had to go. […] It earned its reputation for being the most oppressive state in the Union.”

To take the MCAT to get into medical school, Smith had to be escorted to the exam room at Millsaps. Almost all Black physicians studied at either Howard or Meharry, historically Black medical schools, and Smith chose Howard.

He became an ob-gyn resident in the Cook County Hospital serving Chicago, an important step in his career. But in 1961, soon after he began his residency, Smith was called back to Mississippi by the state government, which needed to provide 12 physicians to the U.S. Army during a period of national conscription in the midst of the Berlin Crisis standoff. Mississippi was not accepting Black physicians in residencies within the state, but they found and located Smith to use for their quota.

“I felt angry and upset, being the first Black to have achieved this residency, then segregation and discrimination brought me back to Mississippi,” Smith says. He had planned never to return.

Forced to wait around in Mississippi for six months, where activists were trying to integrate downtown Jackson, Smith became exposed to the rhetoric and fire of early civil rights organizers like his friend Medgar Evers, the NAACP’s first field officer in the state, who would later be assassinated by a white supremacist. Smith attended Evers’s weekly meetings.

“It was an awakening,” Smith says. “I saw it as an opportunity for medical, social, and economic change. Things were so damn bad, I felt it was a privilege to put my career on hold and become a foot soldier, realizing I was no different from anyone else. And that some of the changes I was working for would be enhanced by my becoming a foot soldier. And I couldn’t have been more right about that.”

Smith became one of a handful of Black physicians who returned to his home state to practice medicine, working within a segregated hospital system that prevented him from having the same access to facilities as his white colleagues. He saw thousands of Mississippians, mostly poor Black families, going without medical care and forced to deal with ailments such as worms and anemia on their own. Blacks were turned away at some hospitals or shunted into unclean wards.

Smith formed the Southern branch of the Medical Committee for Civil Rights (MCCR) in 1963 to protest the American Medical Association (AMA), which allowed southern medical societies to remain segregated and often kept Black physicians from being employed at hospitals. (In 2017, the AMA awarded Smith the Medal of Valor for his work.)

The following year, Smith became the Mississippi organizer behind the Medical Committee on Human Rights, providing medical services to civil rights activists throughout Freedom Summer, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s march from Selma to Montgomery.

Smith said he was lucky to never experience direct physical violence himself: “One thing I would tell the police when they would harass me is just ‘Don’t hit me.’ My daddy always told me to look a man in the face and tell him ‘Don’t hit me.’”

Brown-Tougaloo’s mixed beginnings

In the early 1960s, just as Smith was becoming involved in the civil rights movement, his alma mater, Tougaloo—a Native American word roughly translated as “at the fork of the stream”—was running into opposition from Mississippi’s political establishment.

“Things were so damn bad, I felt it was a privilege to put my career on hold and become a foot soldier [for civil rights].”

Tougaloo’s president, A. Daniel Beittel, had drawn the wrath of Mississippi white supremacists for supporting his students’ engagement in the civil rights movement, even attending sit-ins to ensure their safety. The college was struggling to survive as the state attempted to revoke its charter.

It was at this “inauspicious moment,” according to a speech delivered for the 40th anniversary of the partnership by Brown alum and Tougaloo trustee Peter Bernstein ’73, that Brown entered into a formal partnership to help Tougaloo in 1964. There were several people on Tougaloo’s board in the early ’60s who had links to Brown and Providence. One was Irving Fain, a wealthy, philanthropic Providence businessman whose wife had grown up in Mississippi. Another was the Rev. Larry Durgin, minister of Providence’s Central Congregational Church—where Brown President Barnaby Keeney happened to be a parishioner. Durgin had become a member of the Tougaloo Board through his work with the American Missionary Association, which, after the Civil War, established more than 500 schools in the South, one of them Tougaloo.

Fain, Durgin, and Durgin’s former assistant minister Charlie Baldwin—who’d just been appointed Brown’s chaplain—formed the Rhode Island Friends of Tougaloo to raise money for the struggling college, Bernstein said, and asked Keeney for help. Keeney, in turn, had just attended a conference where President John F. Kennedy had urged leading educators to increase their efforts to expand educational opportunities for Black Americans. So Keeney, Bernstein said, saw Tougaloo as a way for Brown to “play a useful role in Black higher education.”

The role smacked of paternalism from the start, according to former Brown history professor Jim Campbell, in his introduction to Brown’s online archive of the Brown-Tougaloo partnership. First, Brown’s support coincided with Beittel’s resignation, allegedly through the machinations of Keeney, who was worried that a social-activist president would cause unnecessary distractions.

Then the partnership’s first project was to “teach Tougaloo students to speak ‘standard’ English,” versus “nonstandard dialect,” a program that ran from 1965 through 1969. A number of Tougaloo students questioned the value of mainstreaming and integration, the program’s goals. And by 1967, writes Campbell, “Black Power leader Stokely Carmichael memorably denounced the cooperative project in a speech at Woodward Chapel, claiming that Tougaloo had been reduced from a Black college to a ‘Brown baby.’”

Despite the rough start, there were genuinely transformative elements of the partnership for both Brown and Tougaloo students, especially for medical students. Thanks to a program started by founding Warren Alpert Medical School dean Stanley Aronson, top Tougaloo pre-med students could receive full scholarships to study at Brown’s medical school, while Brown medical students received the opportunity to volunteer at Smith’s clinic.

“They would live among patients of ours at the clinic to get a real taste of what poverty was like,” Smith says. “They had the opportunity to be exposed to different cultures and also at the same time to realize how very similar we are.”

To highlight the influence of such experiences, Smith points to Seth Berkley ’78 ’81 MD, a Brown-Tougaloo alumnus who went on to found the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and who remains at the forefront of funding and distributing affordable vaccines. Many others went on to careers focused on community-centered public health, some returning to Mississippi to address the physician shortage.

“The uniqueness of this program was the fact that many people got a chance to see, experience, and get closer to some of the root causes of poverty and poor health and work to create avenues for solutions,” Smith says.

Transforming healthcare in Mississippi

In 1965, Smith and fellow activists secured funding from the Office of Equal Opportunity to launch a pilot community healthcare clinic in Mound Bayou, Mississippi. To get the funds, they had to sneak a proposal past James Eastland, “the godfather of Mississippi politics,” who used his leverage on the U.S. Senate judiciary committee and his congressional clout to stymie civil rights legislation.

The coalition behind the proposal for community health center pilot funding, which included the activist physicians Jack Geiger and Count Gibson, noted there would be two sites for the centers, one in the north and one in the south.

“Anything that was designed to help Mississippi was blocked,” Smith says. “In that initial proposal, we said “a southern site”—we didn’t say Mississippi, even though we knew that [it would be there] from the very beginning.”

The pilot program in the South launched what is now known as the Delta Health Center in Mound Bayou, a small town on the Mississippi delta founded by former slaves, receiving federal funding to serve neighboring counties with high poverty rates. Along with providing healthcare regardless of patients’ ability to pay, the center offered environmental, social, and legal services. “It continued…despite opposition and every imaginable attempt to destroy it,” Smith said in an oral history. “There were threats of violence and the whole nine yards.”

“One thing I would tell the police when they would harass me is just ‘don’t hit me.’ My daddy always told me to look a man in the face and tell him ‘don’t hit me.’”

There are now 21 community health centers in Mississippi alone, reaching around 300,000 people, and approximately 1,400 similar health centers across the nation, according to Smith.

Smith says he remains moved by the appreciation of his patients for the care they receive. Many who cannot afford the cost of healthcare still try to bring Smith sacks of potatoes, bowls of fruit, or coupons for meat. They invite him to weddings, funerals, and all kinds of social events and ceremonies as ways to show their appreciation and thank him. He says he’s had to start finding ways to politely refuse, in order to still have time for his own family.

“Contrary to what people believe, poor Black people are just like poor people everywhere,” Smith says. “What they just want is respect and good care. They want to pay, but many times they just didn’t have any money to pay.”

While proud of the health infrastructure he helped establish in Mississippi, Smith remains ambivalent about Mississippi’s healthcare system, noting that more than a third of the state’s population still qualifies for the subsidized Mississippi Health Center where he works. Mississippi is one of 12 states that has not passed Medicaid under Obama’s Affordable Care Act. More than 30,000 state residents are estimated to have no access to health insurance or subsidized health coverage.

“I still live in a place where we compete for 47th, 48th, 49th for being the most obese state, for having the highest infant mortality rate,” Smith says. “I just have to take some of those things off my mind to be able to go to sleep at night.”

At 85, Smith still comes into the office at Central Mississippi Health Services most days, intent as ever on improving access to affordable healthcare in his community.

“We’re still a long way from home,” Smith says. “But we have made some tremendous strides in my lifetime.”

Jack Brook ’19 is a reporter at the Southeast Asia Globe in Phnom Penh. His writing has been published in the Christian Science Monitor, Jerusalem Post, Miami Herald, Marshall Project and other outlets.