Roots, Reconnected.

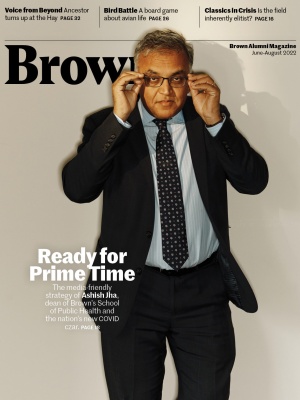

A book of Afro-Indigenous poetry found in the Hay Library reunites two women across generations.

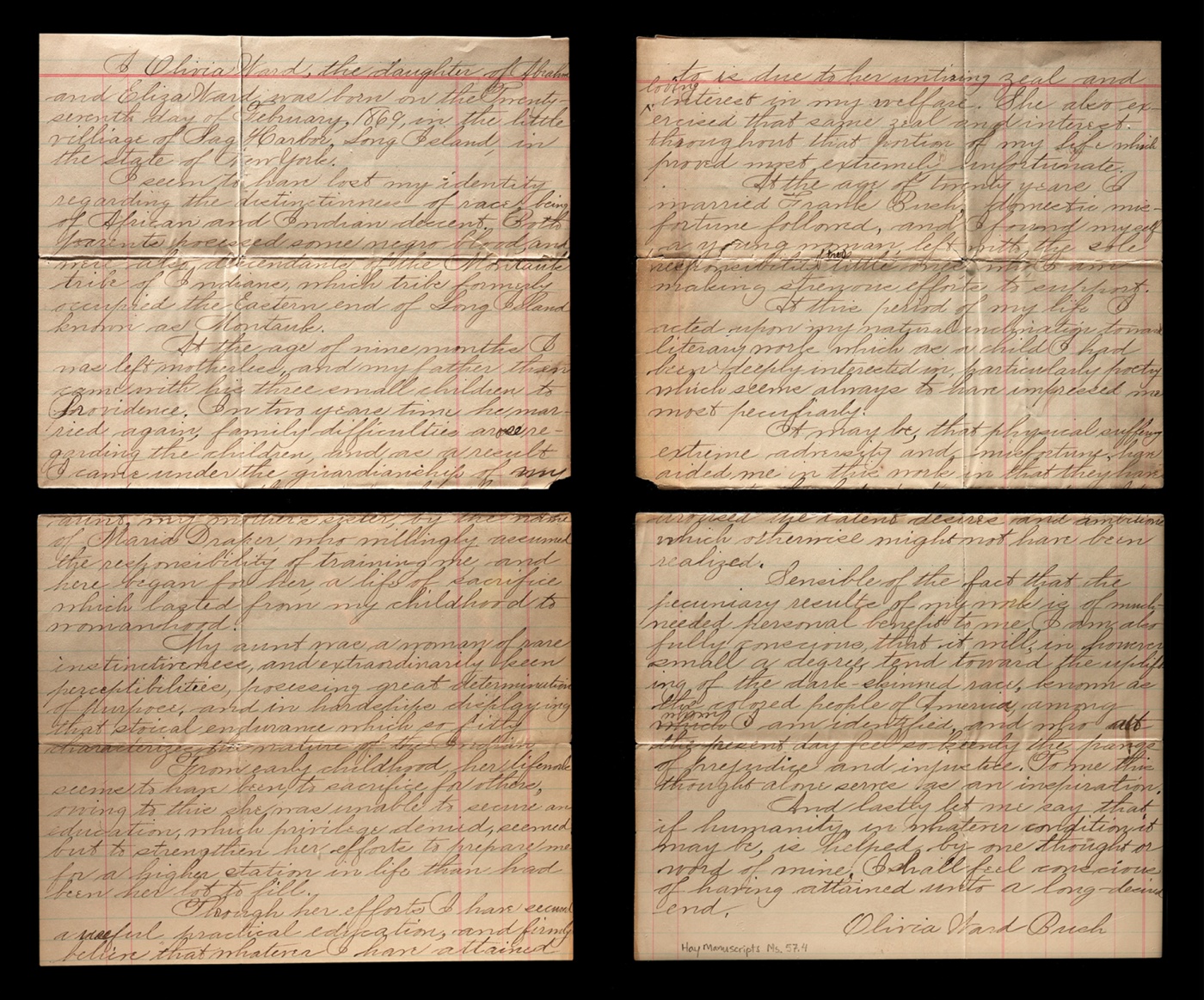

“My work… will, in however small a degree, tend toward the uplifting of the dark-skinned race, known as the colored people of America, among whom I am identified, and who at the present day feel so keenly the pangs of prejudice and injustice. To me this thought alone serves as an inspiration.”

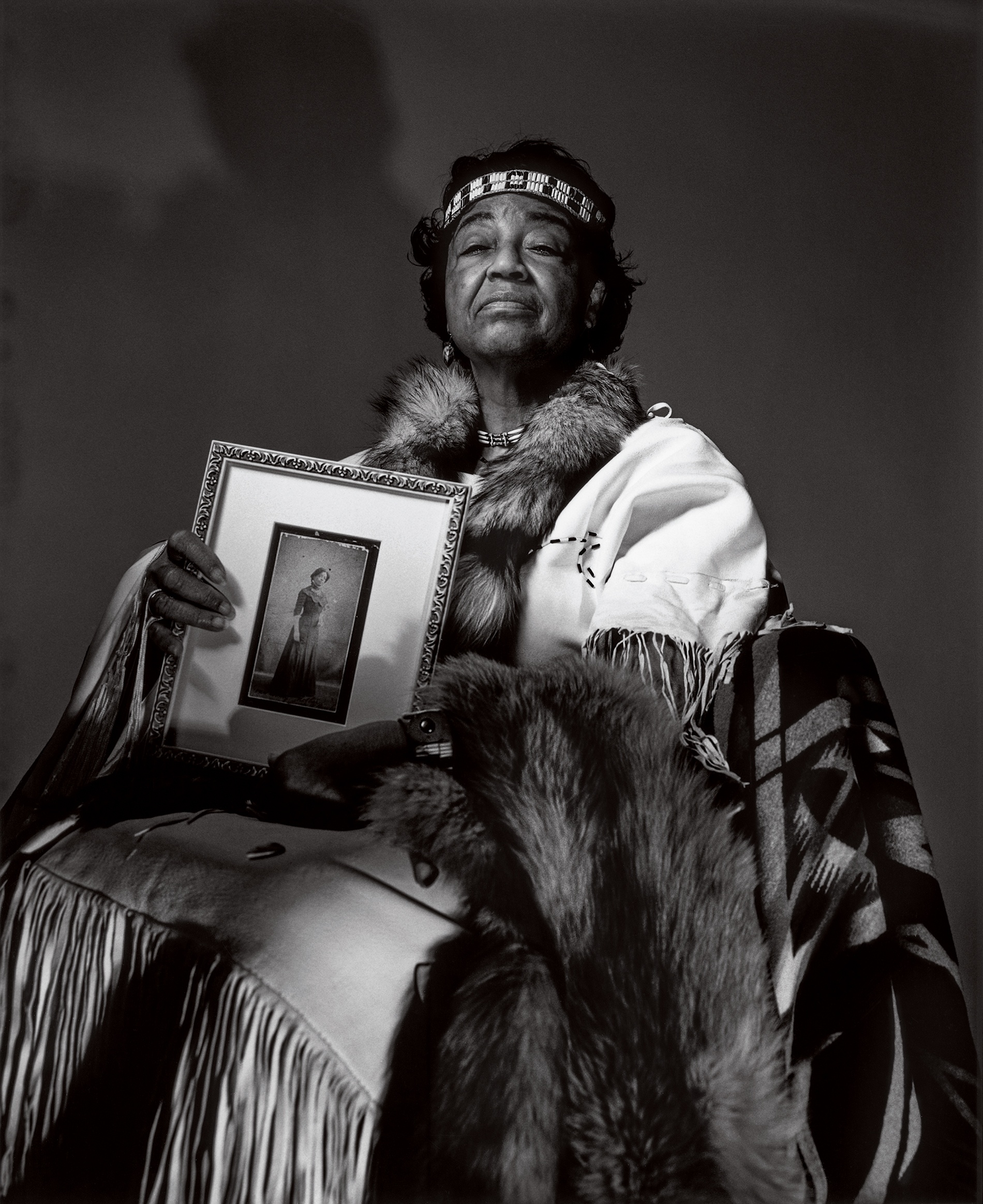

Nearly 50 years after seeing her great-grandmother’s autobiographical letter for the first time in the John Hay Library, Bernice Forrest ’74 AM’s face still lights up as she reads it aloud. “And lastly let me say that if humanity, in whatever condition it may be, is helped by one thought or word of mine, I shall feel conscious of having attained unto a long-desired end,” concludes Forrest, beaming. “Olivia Ward Bush.”

Now printed at the start of Olivia Ward Bush-Banks’s complete poetry anthology, which was compiled and edited by Forrest, the letter was once a single set of yellowed pages tucked inside a hand-bound collection of “Original Poems” (as the document is titled) from 1899. For decades, the volume lay gathering dust in the alcoves of the John Hay Library, until Forrest retrieved the document at the advice of a cousin. When Forrest cracked open the dusty cover in 1974, she says the checkout record showed she was the first person to lay hands on it in nearly 75 years.

“I was spellbound. I couldn’t even breathe,” Forrest says of the handwritten note inside the book. “It was a back-to-the-future moment: from 1899, it felt like she was writing to me.”

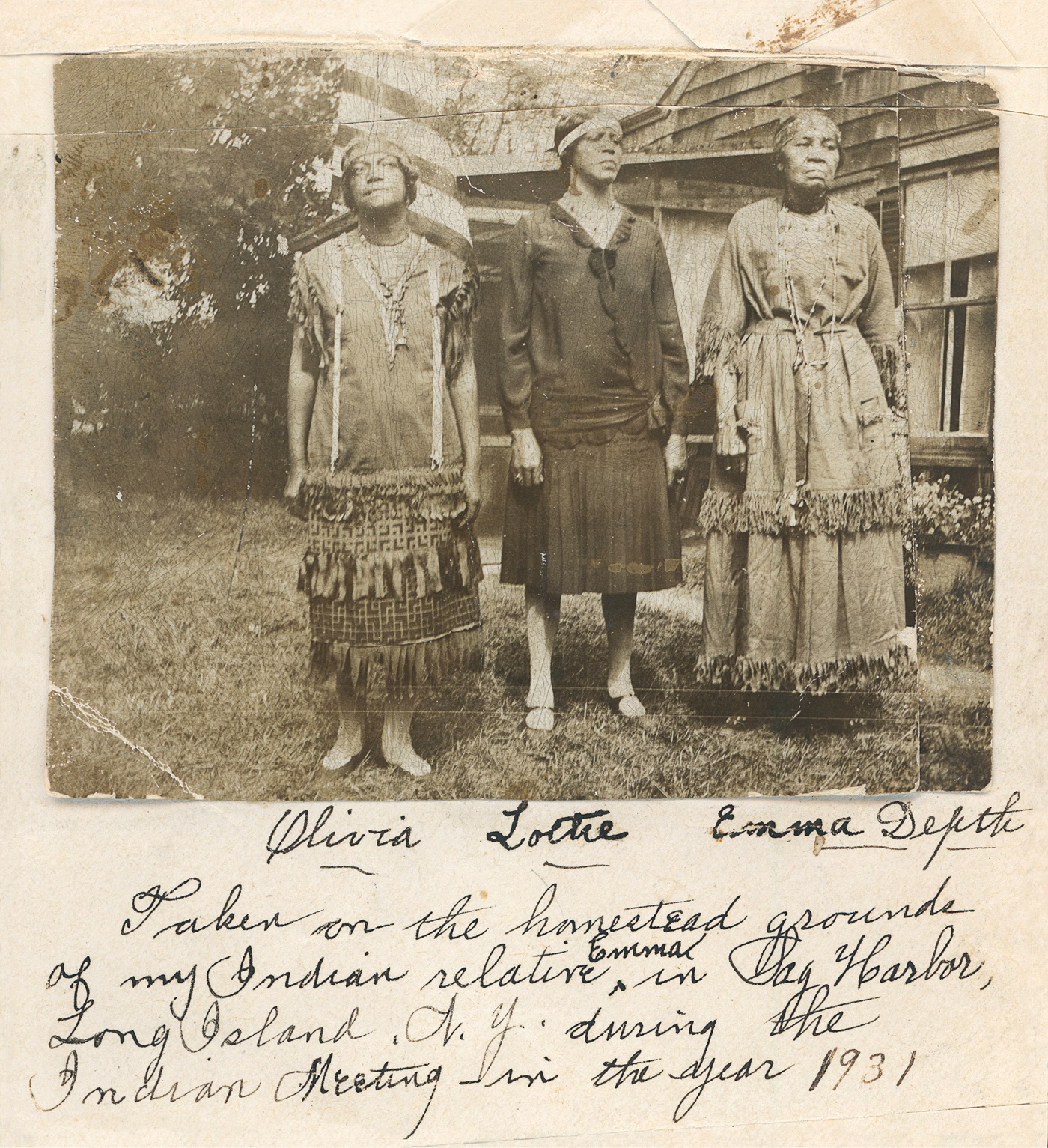

Born in the winter of 1869 to parents both of mixed Black and Montaukett tribal descent, the writer and historian then known simply as Olivia Ward spent the majority of her early life serially uprooted: from Long Island, her father moved the family to Providence in the early 1870s before giving his youngest daughter away to be raised by her maternal aunt. It was while attending high school in Rhode Island that young Olivia developed her passion for the pen, as well as a keen eye for the undercurrents of the civil rights movement that were already swirling in the late 19th century. Consorting with the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson, the Harlem Renaissance–era writer split her adult career between advocating for the rights of African Americans and working furiously to preserve her Indigenous heritage back on Long Island, in the role of historian for the Montaukett tribe.

A doublet of marriages lengthened the poet’s name and lineage considerably; by the early 1900s Bush-Banks boasted three children and numerous grandchildren, though her relationships with her progeny were not trouble-free. Most notably, Bush-Banks’s estrangement from Rosamund, her eldest daughter and Forrest’s grandmother, is widely thought to be the stimulus behind one of her most famous poems, “Regret.” The final lines, “Tears of deep regret could not unsay / The thoughtless word I spoke that day,” are considered a reference to the fact that Rosamund died as a young woman, before the two could reconcile.

The discovery of Bush-Bank’s letter and poems transformed Forrest. She got her PhD at Tulane, eventually finding herself inescapably drawn back to her great-grandmother’s work and the revelations it held for her own mixed identity.

“At that time, I had no intention of pursuing genealogical research and Indigenous ethnohistory in southeastern New England,” says Forrest, an associate professor of history emerita at University of Colorado, Colorado Springs. “But life possesses a cyclical rhythm, and mine ultimately revolved around my maternal Indigenous heritage and the complexities of navigating multiple ‘cultural identities.’” Amid other research endeavors, Forrest devoted herself to compiling all of Bush-Banks’s poems together into a single anthology, whose first edition was published in 1991. Despite feeling intimately tied to her great-grandmother’s work, Forrest elected not to disclose her connection to Bush-Banks when the collection was initially published because she “knew the work must stand or fall by itself.”

And stand it did, both among the records of prominent institutions like the New York State Capitol—where Bush-Banks was honored in a 2012 exhibit entitled “New York’s Women Leading the Way”—and within Forrest’s relationship to her own family and its Afro-Indigenous and Scottish origins. Cradling her copy of The Collected Works, left thumb absently perusing its pages, Forrest recalls her first encounter with racial discrimination, as a fourth-grader playing tetherball on the school playground. The shock and dismay return to her face as she describes the little white girl that came up to her with “the most vicious look in her face” and declared Forrest a “light-eyed bitch.”

“I was spellbound. I couldn’t even breathe,” Forrest says of the handwritten note. “It was a back-to-the-future moment: from 1899, it felt like she was writing to me.”

For years after that moment, Forrest remained self-conscious about her dusky eyes, how sharply they stood in contrast with her darker skin and how different they were from the rich browns of the other Black women around her.

“I hadn’t really been looking in the mirror [before then],” Forrest says. “But then I looked more closely at my mother, who was dark-eyed, and said to myself, ‘Well, who am I?’” Quietly, the question haunted Forrest for years, until finally, the discovery of Bush-Banks’s words provided the American Studies student with a comfort and closure she hardly knew she was seeking.

“It completed my soul, and then some,” Forrest explains. “Because I was free to know, and then to go out and keep searching.”

The intergenerational traces of Bush-Banks’s influence continue into the present. Armed with the knowledge of her Indigenous roots, Forrest brought her son, Paul Guillaume, to powwows as a child, even gifting him the Native American name of Bear Who Walks Through the Night. Following in his mother’s footsteps, Forrest also became a teacher, and seated next to Guillaume on her living room couch, he appears equally rapt by the contents of the book in her lap.

“When I think of these women, Olivia and my mother, one word describes the both of them: pride, both in who they are and where they come from,” Guillaume says. “A lot of pride, and a lot of love for the ancestors.”

Ivy Scott ’21.5, a CASE award-winning former BAM intern, is a criminal justice reporter at the Boston Globe.