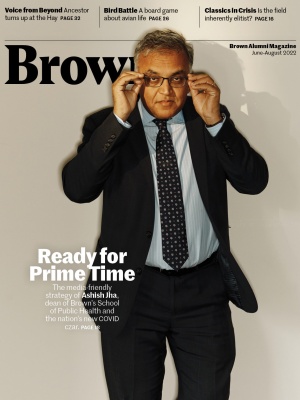

Excavating Joy

Martha Sharp Joukowsky’s renowned field methods included a liberal dose of fun

From the dunes of Jordan to the halls of the Joukowsky Institute for Archeology, students, friends, and family are excavating memories of Dr. Martha Sharp Joukowsky, an energetic professor, generous mentor, and passionate academic who died on January 7.

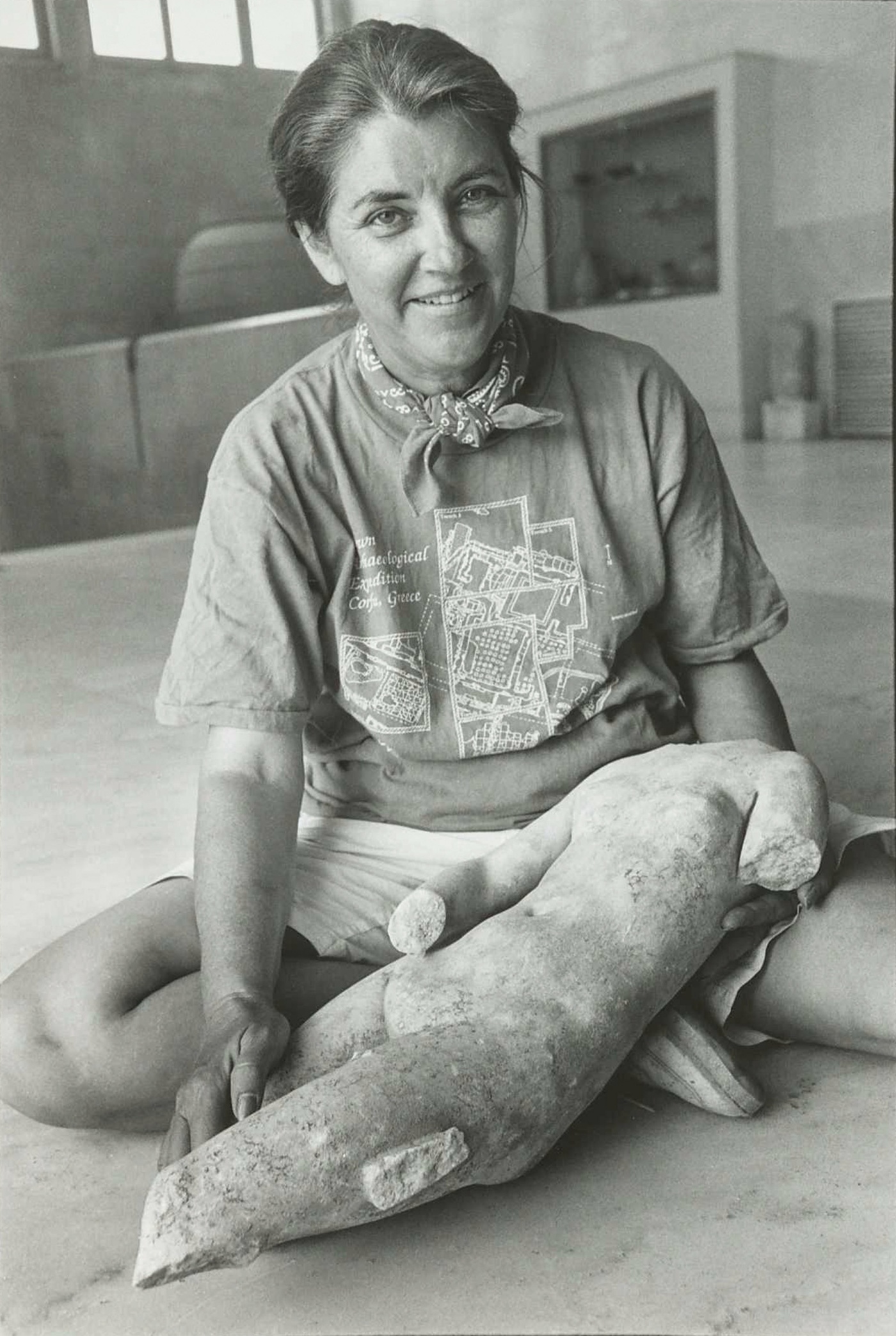

Over the course of her career, Joukowsky carried out archeological fieldwork in countries ranging from Greece to Hong Kong, producing a record of insights into the past. “She loved what she did every second,” says her son Michael Joukowsky. “It was professional playing.”

Yet the joy of her work was bound in intellectual and academic rigor. She completed her PhD dissertation on the prehistory of Western Anatolia (now modern-day Turkey), defending the thesis in French over three days at the Sorbonne, where she received the highest possible honors. Later in her life, she spent 15 years unearthing history at the sand city of Petra, an opportunity she shared with dozens of students over the years as a professor of old world archeology and art and of anthropology at Brown from 1982 to 2002.

“The students would call her mom,” Michael says. “Everybody who walked into her classroom, you were an extension of her family.”

Known for putting an extra touch to her archeology classes, she included sandboxes to practice digging and field trips to the MET. She converted her basement to a classroom filled with books, the slides from her lessons available on a carousel and the keys to her home regularly handed out to students. As students crammed during late-night finals sessions, Joukowsky would appear in her night robe to answer questions, former students recall.

“She knew every single student in all of her classes and she really took a very personal interest in all of them,” explains Tarek Khanachet ’03, a student who joined her for several Petra digs. “She was just an endless source of advice, of guidance, of comfort.”

Joukowsky’s fieldwork in Petra exploring the Great Temple added to “our growing understanding of the complexities of cultural interaction on the edges of empire,” says Dr. Laurel Bestock, associate professor of Archaeology and Egyptology/director of graduate studies at the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology.

On the College Green, a replica of an ancient limestone elephant Joukowsky discovered on site greets those entering the Joukowsky Institute, a sunlit space of learning that elevated the University’s archeological studies into an internationally renowned, interdisciplinary hub. But perhaps even more than the overt displays of generosity manifesting in the campus buildings she and her husband established, Joukowsky’s legacy lies in the consistent and life-changing opportunities and mentorship she provided to her students.

Bestock remembers approaching Joukowsky as a nervous first-year student to inquire about working on the summer Petra dig. While Joukowsky at first said she never took freshmen, she invited Bestock to her home for lunch and then, at the end, agreed to bring along Bestock and cover the costs.

“She created an environment and had the personal generosity to invite people into that environment and give them responsibility within it,” says Bestock.

Students usually received their own “trenches” to excavate and manage. Digs began at sunrise, carrying on through 110 degree heat surrounded by flies and punctuated by long tea breaks with the Bedouin community. For many, it was one of the most rewarding experiences of their lives.

“She trusted that you would do a good job, and that you were going to be meticulous, and you were going to be worthy of that responsibility,” remembers Emma Libonati, who joined the Petra digs as an undergraduate and now teaches archeology at the University of East London.

“She loved what she did every second. It was professional playing.”

Joukowsky made sure the findings from the digs were always published, even posting her Petra data online in an open access format to ensure a wider reach.

“One of the reasons Martha became so prominent in the world of academic archeology is that her book on field methods is considered second to none,” Khanachet says. “And we put that book into practice. There was no sloppiness on that dig.”

Her field methods textbook was so beloved and in demand that even after it went out of print, a shop in Puerto Rico spent years publishing illicit copies for the black market.

During her expeditions in Petra, Joukowsky formed close ties with the local Bedouin community, many of whom worked alongside her for years. The community even named a camel after her, her son Artemis recalls.

“She really was about cultural preservation and the empowerment of local communities to see their archeological digs as a cultural imperative for that community,” he said.

Students reminisce over her “Martha-isms,” Joukowsky’s distinctive turns of phrase such as her evening “knitting,” the code for 5 p.m. cocktail hour at the end of a hard day’s work in the field. A student might fondly be referred to as a “dead-loss” or greeted by a gravelly laugh and a “What’s going on?”

“She was just this powerful presence, always the center of the room but in a really lovely way,” Agnew says. “She made everyone around her better.”

A chain-smoker, Joukowsky on occasion donned a bandolier filled with dozens of lighters that students had gifted her, draped over her khaki field duds, expedition hat, and sunglasses. She appreciated a good joke, keeping up the legacy of the legendary myth of Professor Josiah Carberry throughout her life, says her close friend, Connie Worthington. At home, a flock of dogs, named after the Nabataean gods of Petra and deities from other ancient civilizations, frolicked about her.

Joukowsky also committed herself to building up Brown’s institutions and campus spirit. With her husband, Artemis A. W. Joukowsky, who died in 2021, she founded the Sheridan Center to cultivate teaching and further the aims of the Open Curriculum. Passionate about the Brown Women’s swim team, she attended meets and practices as a faculty advisor for more than two decades.

Throughout each stage of her career, she was often accompanied by husband, whom she met at Brown as an undergraduate when he watched her perform as a witch in a production of Lady Macbeth. The two were married for more than six decades. In his retirement, Artemis Sr. worked as a site photographer, documenting his wife’s fieldwork and findings.

“I think the really beautiful thing was seeing my mom and dad work as a team,” says their son, Artemis III. “They had this indefatigable passion for each other's passions and they supported each other deeply.”

Joukowsky is survived by her three children, eight grandchildren, and numerous friends, supporters, and colleagues, as well as the scholarships, buildings, and programs she and her husband established at Brown and across the world.