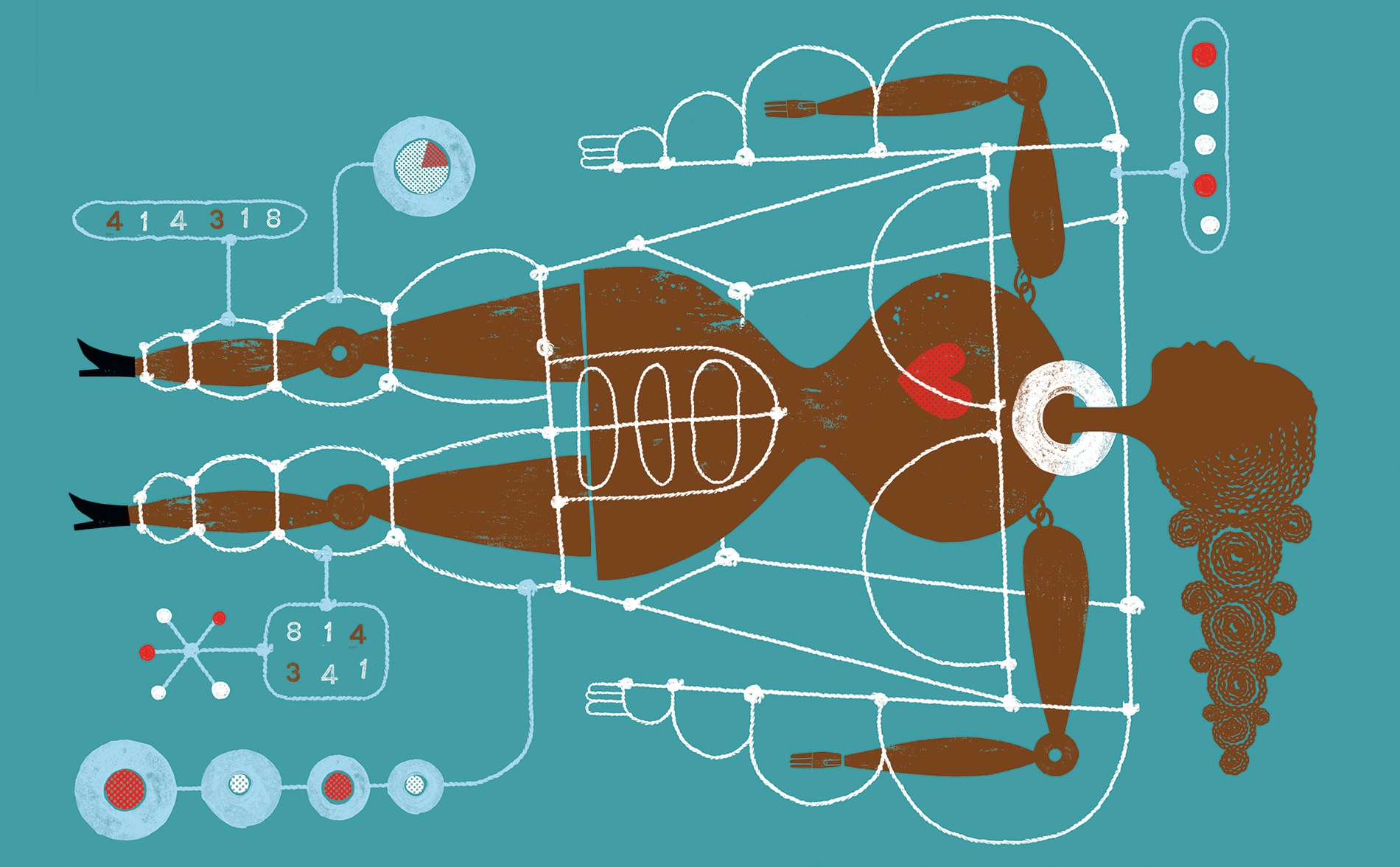

Beyond the Average White Guy

Experts are moving past biological sex to “precision medicine” that takes each individual patient—whatever their gender—into account.

It is a battle every single time. People don’t see why we need to talk about asthma in women, or sleep disordered breathing in women, or lung cancer in women,” says Ghada Bourjeily, a Brown professor of medicine and expert in pulmonary disease and pregnancy.

“We have been studying males who are mostly white, who are 20 to 40 years old,” explains Alyson McGregor, director of the Sex and Gender in Emergency Medicine program at the Warren Alpert Medical School. Traditionally, she says, scientists have been educated to believe that “the male model was accurate for everyone else.” The consequences can be deadly. For instance, women are still 50 percent more likely than men to be misdiagnosed during a heart attack, a 2016 University of Leeds study found, as providers tend to look for the “classic” symptoms—what a heart attack looks like in a man—rather than the shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, and back or jaw pain that women are more likely to report.

Sex-specific research isn’t just about improving women’s health, McGregor says. It’s delving deeper into questions such as why COVID-19 kills men at a higher rate than women. Research points to the role of testosterone, an androgen that helps COVID-19 viruses get into cells, she says. “When you conduct research that separates out and compares data from men and women, it’s actually about a better and higher quality of research for everyone,” McGregor adds. “Both men and women will have benefits.”

Cardiac arrest and COVID-19 are just the beginning. In order to tailor our treatments to each individual’s physiology—an approach called precision medicine—providers should consider genetic and physiological factors, specific pathophysiology, as well as gender and cultural roles, a patient’s environment, and race. Another “huge research gap” is transgender individuals’ health: exogenous hormones, which might be taken during a transition, can affect health and long-term risk of stroke or heart disease, says Tracy Madsen, a Warren Alpert Medical School associate professor who holds multiple titles, including director of clinical research in the department of emergency medicine, codirector of the R.I. Hospital and Miriam Hospital stroke centers, and associate professor of epidemiology in the School of Public Health.

At its core, the work of those who study sex and gender in medicine is about bringing us closer to personalized medicine for all. After all, when it comes to health, the one-size-fits-all approach simply doesn’t work.

Costly assumptions

Every year, over 759,000 people experience a stroke in the U.S.—and not only are women 33 percent more likely to be misdiagnosed than men, but racial minorities are also 20 to 30 percent more likely to be misdiagnosed. While both women and men often present with “classic” symptoms—paralysis or sensory loss on just one side of the body, changes in vision, and dizziness—women are more likely to present with additional symptoms. “Sometimes that can make the diagnosis in the acute setting more challenging, and stroke is a very time-sensitive diagnosis,” says Madsen.

Provider bias also plays a role in pulmonary care, says Bourjeily. Even when women and men present the same symptoms, they can receive different diagnoses. “If a woman comes in and says, ‘I am wheezing and I am short of breath’ and a man comes in and says he’s wheezing and short of breath, the woman might be more likely to be diagnosed with asthma, the man more likely to be diagnosed with COPD,” says Dr. Bourjeily. “In COPD”—which includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis—“there is a delay in the diagnosis in women.”

Ideally, she says, we would have criteria and protocols that insist providers not make assumptions: “If you have these symptoms, regardless of what your sex is, you need these investigations.”

Hormones at play

Madsen’s work focuses on stroke and the how and why behind sex-related differences. For example, how do conditions like diabetes and high blood pressure affect men and women differently when it comes to stroke risk? Her recent work centers around the role of sex hormones in the development of stroke, particularly SHBG, a protein that transports sex hormones like testosterone and estradiol. SHBG has a known role in diabetes and other cardio-metabolic factors, says Madsen: “We’re using that particular biomarker as a focus to learn more about the mechanism of stroke for women across the lifespan.”

Sex hormones are a factor in the pulmonary system also, says Bourjeily. Female sex hormones may affect airway behavior, exacerbate lung disease at specific times in the menstrual cycle, or contribute to asthma worsening in pregnant women, she says. There’s a lot more that we don’t know: “That is a field that still needs to be explored quite a bit.”

Life stages

While symptoms and response to medications can vary widely between patients with XX chromosomes versus those with XY or other chromosomal configurations, what one patient looks like at 20 can be different from that same patient at 60. In her research on stroke, Madsen pays attention to how a woman’s physiology changes over her lifetime. “In the years following menopause, the risk of stroke increases dramatically,” she says, “and we still don’t have a great understanding of why.”

Bourjeily’s research focuses on understanding the factors that predict which patients develop sleep-disordered breathing in pregnancy. She also looks at the relationship between life stage and healthcare compliance. In women of reproductive age prescribed sleep apnea therapy, “her societal role, her understanding, and her acceptance of certain things is completely different than what she would accept when she’s post-menopausal for instance, or in her sixties.” Being sensitive to these factors, she says, is part of precision medicine.

McGregor aims to educate future doctors so that they incorporate these issues into their research and practice. She has worked with leaders in medical, pharmacy, dental, and nursing schools nationwide and has placed women’s health research under the national public spotlight with her book Sex Matters: How Male-Centric Medicine Endangers Women’s Health and What We Can Do About It.

“Things are slow to change, but I think people are eager,” says McGregor. She adds that she, and “so many colleagues and so many wonderful women scientists that came before me, have really tried to get all the pieces so that we’re creating awareness throughout the whole system.”