The Latest on Distraction

The rise in ADHD diagnoses has researchers asking what’s behind it—and whether it's really such a bad thing

ADHD diagnoses have increased since the first national survey in 1997, and we’re not sure if that’s due to rising prevalence or increased awareness. The once controversial diagnosis has gained legitimacy, and with it the assumption that diagnosis is good, mobilizing resources and better outcomes for the kids.

But Jayanti Owens, assistant professor of sociology and international and public affairs, wondered if it helps everybody. For diagnosis a child has to exhibit problems with attention, self control, and self regulation in at least two contexts—usually home and school. So imagine two students with mild levels of inattention and hyperactivity. If one is in a slightly chaotic classroom and another in a more disciplined environment with expectations of sitting still and listening quietly, who gets noticed?

Owens looked at kids diagnosed between kindergarten and third grade, measuring behavior in fifth grade and academic outcomes in eighth grade. She found the diagnosed mild cases did worse than those who are not diagnosed, whether or not they received medication.

The problem is exacerbated for kids of high socioeconomic status. They’re in an environment where they are more likely to be noticed. Their parents, believing it’s in their kid’s interest, are more likely to push for a diagnosis—and not only have resources, but know how to mobilize them.

“A lot of these kids are getting diagnosed,” says Owens. “And it may not be helping them.” She stresses that millions of kids really need and benefit from diagnosis and treatment, but we should also be thinking more about where the benefits lie.

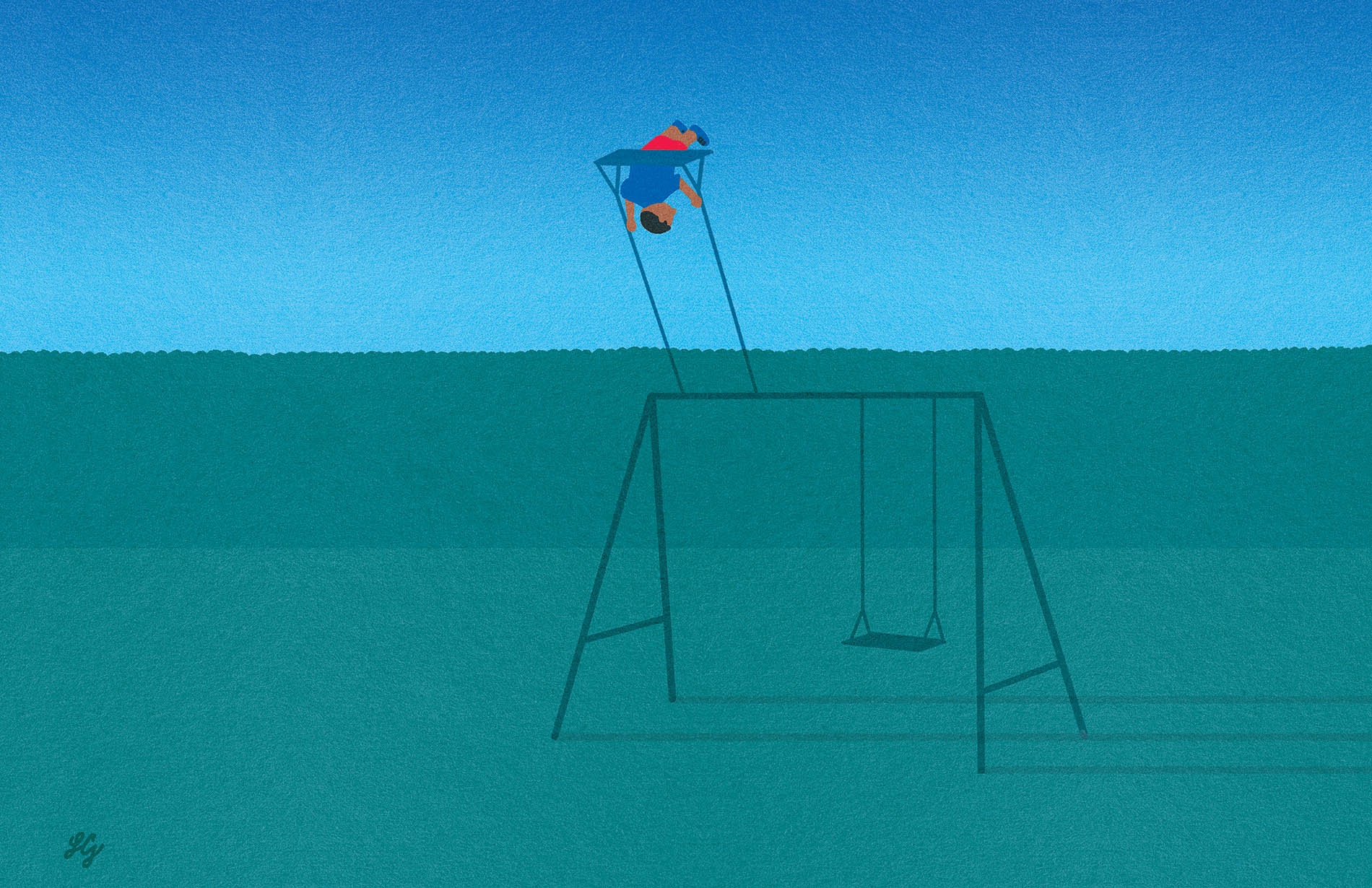

“There could be alternatives like making sure your kid is getting enough sleep, limiting screen time, and getting enough outdoor playtime,” she says. “What presents as inattention or hyperactivity could really just be the result of a lack of other needs being met.”

The chemical connection

There is no shortage of popular theories about what causes ADHD, and plenty of emerging research. We don’t know a lot with certainty because the condition is clearly complex. Joseph Braun, associate professor of epidemiology and director of Brown’s Center for Children’s Environmental Health, was drawn to the field because of his own childhood ADHD and parallels he saw in how environmental chemicals led to behavioral disorders.

Now he works with a group on a long-term study of kids born to 468 mothers in Greater Cincinnati between 2003 and 2006. Early results helped dial in the role of lead and nicotine exposure as risk factors for ADHD. Lead is known as a bad actor, but screening guidelines focus largely on kids three and younger at high risk of ingesting environmental lead in their homes. “What we’re not thinking about is, maybe kids continue to have lead exposure as they get older,” Braun says. “We might be missing an opportunity to prevent neurodevelopmental disorders like ADHD if we don’t continue screening.”

In 2019 Braun’s Cincinnati work helped connect ADHD behavior to triclosan, a common antimicrobial compound used in consumer products and frequently detected in the urine of pregnant women and children.

Now he and his collaborators have expanded their search to encompass a much bigger collection of suspects. More than 80,000 chemical compounds are used in industry and commerce right now, and few have been properly scrutinized for health effects. Even less is known about how they interact.

Braun and his research partners now have data on nearly 100 different common environmental contaminants at multiple stages of life from gestation into adolescence. Lead, nicotine, triclosan—these are very different substances, working in different ways, yet they all are implicated in ADHD. “What happens when you add them up?” he asks. “That’s what we’re trying to figure out.”

ADHD and sleep

A bad night’s sleep is a good starting point for understanding the ADHD experience. Difficulty paying attention? Fidgeting? Energy swings? Impaired memory? Fatigue and impulsivity? “Those are all things that you could use to describe sleep loss—and ADHD,” says Jared Saletin, assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and associate director of the E.P. Bradley Sleep Research Lab.

Comparing imaging research on acute sleep deprivation and ADHD, Saletin’s team found an overlap in the frontal lobe, the parietal lobe, and the anterior cingulate cortex. In these areas people with ADHD looked like people who missed out on a good night’s sleep. They also noticed that for people without ADHD, an arousal network in the thalamic region of the brain was more active after sleep deprivation, potentially acting as a buffer. “Folks with ADHD didn’t have any compensatory signal that could potentially mitigate those losses,” says Saletin. For them, sleep deprivation—bad for anyone—could be exponentially worse.

Most school schedules are blind to the sleep needs of developing children. “What happens if that brain, already struggling to pay attention, gets further sleep deprived?” asks Saletin. He’s trying to find out, beginning a five-year sleep study on children with ADHD and similar conditions.

Most importantly, we now know a lot about fixing sleep. “It’s remarkably modifiable,” says Saletin. “I can get you to sleep better at night without medication. With just small changes to behavioral routines, we can get people to sleep a little bit longer, a little bit more structured, a little bit less varied, and more aligned with their circadian rhythm.

“Sleep touches on every facet of a child’s physical and mental health,” he adds. “It can buffer a child’s resilience.”

ADHD Rx: The Open Curriculum?

David Flink ’02 arrived on campus with no plans to discuss his learning disabilities. “I thought talking about dyslexia and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) was the opposite of what I should be doing,” he says. Then he gave his roommate a paper to proofread and got marked down for numerous errors. Surprise: His roommate was also dyslexic.

Flink decided to start talking about it. At the Swearer Center for Public Service, Director Pete Hocking suggested he begin at a local elementary school and Eye To Eye, a peer mentoring and advocacy organization around ADHD and other learning disabilities, was born. Flink wrote a business plan as an independent study and the idea quickly spread. In 2021 he was nominated a CNN American Hero.

ADHD research has helped legitimize the experiences of millions, but Flink cautions that neurodivergence should not be looked at solely through a medical lens, losing sight of the potential strengths that come with the “disorder.” The drugs he was given as a kid were essential to help survive a rigid school environment, he says. But he points out that his unmedicated adult brain is great at juggling multiple ideas, an essential element of running a national nonprofit.

Meanwhile, Brown was a perfect fit. “The curriculum at Brown was so open that my ADHD brain could wander,” he says. “I do not believe I could have thrived and founded Eye to Eye if not for being invited to a space where I could choose on a daily basis what my learning was like.”