Diary of a 9/11 Nobody

An eyewitness account from NYC’s

lockdown zone

lockdown zone

This is an email I sent to my friends in September 2001, referring to it as “Diary of an Irrelevant Person in the Lower Village, Post-Disaster.” The photos of the towers are taken from the terrace of my 12th floor apartment on Houston Street.

Subject heading: What it’s been like here

5 pm, Sunday, September 16, 2001

Five days after the attack

Here I sit barefoot at the table on my terrace, on a beautiful sunny afternoon, surrounded by life and color. At least a dozen yellow jackets are at work gathering pollen from the fragrant new blooms on my sedum plant. The purple basil is flowering, too, despite my best efforts to pinch it back, and the passionflower vines that weren’t supposed to survive the winter have covered the trellis and produced their first two blue-and-white flowers. The white metal railing that stretches the length of the terrace is garlanded with a tangle of honeysuckle and morning glory vines, above nine window boxes filled with geraniums, petunias, and trailing verbena in shades of pink and blue and purple. Ripley is a mass of hot fur lying at my feet on the terra cotta tiles, panting in the bright sunshine.

My garden always brings me peace and joy; the sight and smell of the leaves and blossoms and dirt always helps ground me and makes the city seem more real, more human, more recognizably a home. I can leave the terrace doors wide open all day and imagine I’m in a cottage in the country. But my little patch of life has perhaps never been so reassuring as it is now, as I look over the vines to the cloud of dust and ash still rising through the incomprehensible void in the skyline, up from the rubble of the World Trade Center.

As I write this a seagull flies by, a welcome sight until I realize I’ve never seen a seagull here before, and I wonder if it has come to scavenge human flesh from the disaster site. I hear shouts and applause and look down to the corner, where pedestrians are cheering a flatbed truck carrying a dozen tired men and their shovels and rakes up from Ground Zero.

I’m freelancing right now so I was asleep at 8:46 a.m.Tuesday when the first plane hit. A call from my mom woke me up well after the second plane made impact. She told me what had happened and I got up, raised my blinds and looked out at the burning towers. My view from the 12th floor on Houston Street, about 20 blocks from the towers, was identical to what they were showing on the news. I stood for a long time watching the towers burning, stunned but detached, as it looked exactly like a scene from a movie. I was not yet emotionally connected to the idea of the number of lives already lost. Then as I stood watching, the north tower disintegrated before my eyes. I’m told it took 11 seconds.

One of my lifelong traits is that when there’s a crisis, I get really calm and super logical and I focus on what needs to be done. Sometimes I’m too calm: When my hand was shut in a car door the summer after 9th grade, I calmly and slowly told my friend Ginny, “Please open the car door.” Since I was speaking so calmly, she didn’t pay attention to me until I said it the third time, like a robot, “Please open the car door,” and she looked at my hand in the door and started screaming. But usually my reaction is just right: When my mom and I got held up at gunpoint when I was 19, she became hysterical. I immediately looked down at the floor so as not to make the gunman nervous and my mind went instantly to strategies and possible escape routes should he start shooting. I’m like a crisis Border Collie. I hyperfocus on the problem and do what’s needed to solve it as quickly as possible, without emotion. My tears always come well after the crisis is over.

This was different. The towers were 20 blocks away. Ripley and I were safe. There wasn’t a single useful thing I could do for anyone. But when that tower disappeared into dust, I instantly understood the massive loss of life, the massacre I’d just witnessed as I stood barefoot in my living room in my nightgown, looking through my picture window, and I burst into screaming, weeping, keening hysterics. It was a very long time before I could speak at all, and I was still crying hard, barely able to speak, when I called Arlyn. After we hung up, I stood and watched the south tower burn, then decided I didn’t need to see it collapse, too, so I took a shower. By the time I got out it was gone.

The rest of Tuesday was a blur. I watched the various reports on the disaster on TV, breaking for trips to the supermarket and ATM, to make sure I had supplies and cash to get me through a few days in case water and phone lines went down. My friend Rose Arce was one of the first TV journalists to get to the scene, as her apartment was not much farther away from the towers than mine. She’s a producer for CNN but since the regular on-air reporters weren’t there yet it was Rose on camera. At one point she disappeared from the coverage and I panicked. Finally, she reappeared.

Tuesday afternoon I walked up Seventh Avenue as the ambulances and rescue trucks sped down to the site. People were walking around stunned and quiet. A crowd gathered outside a smoke shop that had set up a TV on the sidewalk, broadcasting the news. Twelve blocks up from my apartment at St. Vincent’s Hospital, the street was cordoned off and the sidewalk was full of medical personnel and office chairs covered with white sheets, ready to serve as a triage area. Ambulances were unloading the wounded, but the office chairs remained empty and the scores of doctors and nurses standing around had nothing to do but drink sodas and smoke cigarettes as they waited for the scores of survivors that never came.

A handwritten sign in my building had said that St. Vincent’s was looking for blood donors and anyone with First Aid experience, so I’d dug out my Red Cross First Aid/CPR certification manual to review it before walking up there. Fifteen compressions for adults; five for children. I paid special attention to the parts about profuse bleeding and broken bones. But there was clearly no need for my paltry knowledge. I walked up to an official-looking woman and asked if there was any way to volunteer and was told they were overwhelmed already and to come back later. The people who were then volunteering were busy posting signs telling potential blood donors to go away and come back the next morning.

When that tower disappeared into dust, I instantly understood the massive loss of life.

When I got back to my block, they’d cordoned it off, too, and I had to show my driver’s license to be allowed back home. They’d searched an abandoned, graffiti-covered truck across from my building for possible explosives, then started to use my block as a parking area for tractor-trailers loaded with rescue supplies. One truck was full of plywood sheets. That seemed odd to me; it seemed a little early to be boarding anything up. I learned later that they were used as stretchers for carrying the dead. A mobile command center was parked at my corner of 6th Avenue, and dozens of dark-green Housing Authority dump trucks and other utility vehicles were lined up and ready, stretching down Houston Street nearly to Broadway.

Back in my apartment, my attention went back and forth from the phone to the TV to the window, through which I could see the thick plume of black and white smoke still rising up from the hole in the skyline and drifting across the blue sky to Brooklyn. With nothing more relevant to do, I started several loads of laundry, figuring I didn’t want to be forced to evacuate my apartment without any clean socks or underwear. The laundry room was deserted; the mundane task and the smell of laundry soap immensely comforting. Walking back to my apartment from the elevator, I could smell that one neighbor’s response to the tragedy was to smoke massive amounts of pot.

I really, really wanted to stay home that night. I’m relatively close to the disaster area, but far enough away to feel safe. Being in my own snug and unchanged environment felt comforting, and my view—though horrific—gave me a sense of control, as I could see at a glance what was going on downtown. But Arlyn and a couple of others insisted that I go to her place uptown, so I packed my clean clothes and Ripley and I set off to see how we could get to West 59th Street, hoping that we wouldn’t have to walk.

Thankfully, the subway was running at West Fourth, the gates tied open—we all rode for free. Ripley was very excited by his first subway ride. (Normally dogs are not allowed, but Tuesday night he was one of the two dogs in our car.) I joined Arlyn and Julie, whose apartment is only blocks from the Canal Street evacuation zone, and we sat glued to the TV till past midnight, with me on edge, feeling like a caged animal, desperate to be home, to see downtown with my own eyes, and to help with the rescue effort somehow. I would have paid for the opportunity to dig through rubble; for the emotional outlet of a real, purposeful response and the physical outlet of hard labor, rather than having to sit there helplessly in front of the TV, marinating in anxiety and adrenaline.

Arlyn’s block was cordoned off, too, because it’s the access road to Roosevelt Hospital’s emergency room. It felt a little like living in a police state. I walked Ripley late Tuesday night up and down the empty block, while the cops at both ends and in front of the emergency room monitored my movements, for lack of anything better to do.

Late Tuesday evening, I suddenly realized my friend Steve might have been working in one of the towers—he used to work for Morgan Stanley—and I called him in a panic. He was fine, but he’d had a narrow escape. Steve worked across the street from the World Trade Center and was arriving just as the first plane hit. He stayed outside and was standing in line for a pay phone a few blocks away to reassure his boyfriend he was OK when the first tower collapsed and sent up an apocalyptic cloud of ash which rushed toward him just like a scene in a disaster movie. Steve ran for his life down narrow Maiden Lane until the force of the explosion and debris knocked him down. Before he could struggle to his feet, the ash cloud had totally engulfed the street. Everything was completely black. He couldn’t see anything, or hear, his ears clogged with ash—he said he remembers the distinct sensation of being underwater, drowning—but then heard someone’s muffled shout: “Walk along the walls!”

Steve felt his way along buildings, wondering if he should try not to breathe, more sounds and hazy shapes slowly filtering in as the ash began to settle. He saw an illumination in the blackness that turned out to be a light fixture above a door to the Federal Reserve Building. He went inside, where rattled armed guards were weighing whether the survivors’ need for shelter outweighed the Fed’s need for tight security. The survivors won out and were admitted to the basement, where the guards gave them bottled water to wash the ash out of their eyes and nostrils. Steve and others stayed there for several hours, then finally were allowed to leave, making their way through the six inches of ash and debris that blanketed the street like a heavy snowfall. Steve walked up to his apartment on 14th Street where, after a very long shower, he emerged with only a few deep cuts on his hands and a lightly abraded face.

Another friend, Louise B., worked six blocks away from Ground Zero. She’d had to run through 30 feet of ash, then she and an elderly stranger in high-heeled shoes had hiked the several miles home to Park Slope, across the Manhattan bridge, wondering if it would be bombed as they crossed it. We’d heard reports from friends miles away in Brooklyn who’d found an office memo, singed but still readable, that had been blasted clear over the East River. I realized the shiny things I’d seen drifting in the black smoke before the first tower collapsed had been pieces of white office paper glittering in the bright morning sun.

Wednesday afternoon, Julie and I couldn’t stand it anymore and walked downtown to see what was going on. I wanted to water my plants and she needed to feed her neighbor’s cats, but mainly we both needed the relief of exercise and to get more of a sense of control by finding out just what was going on in our neighborhoods.

From 59th down to 14th Street, everything seemed a little quiet, but pretty normal. Businesses were open, for the most part, and people went about their lives. There were cops or national guardsmen on major intersections like 42nd and 34th streets, but the most chillingly unusual sight we saw along the way were several Starbucks that were closed up and dark. New Yorkers being New Yorkers, they were casually jaywalking against the red light at 34th, right past the cops and the guardsmen.

On my corner of Sixth Avenue, a lamppost had been turned into a shrine, covered with posters of the missing, American flags, poems, notes and drawings, and surrounded by bouquets of flowers and flickering votive candles.

At 14th Street, police barricades stretched across the avenues and at least a dozen cops, troopers, and guardsmen were at each intersection. Julie and I showed our driver’s licenses to prove we lived downtown, and we were admitted to the lockdown zone.

South of 14th, it felt like one of those long summer weekends when everyone’s out of town, only a little quieter, even. People were out strolling, the mood calm and quiet, but not really somber. I don’t think anyone could really take it in yet. It was another appallingly beautiful, clear day. Supermarkets and delis were open, everything else was closed. There were hardly any cars. Lots of people on their bikes. In the Upper Village there was no trace of disaster, though occasionally we’d hear snatches of conversation about the tragedy or see someone walking around with surgical or allergy masks, and a lot more people with photo IDs hanging around their neck than usual.

In front of St. Vincent’s, the sidewalk was still closed off, but relatively clear of medical personnel. The press had set up across the street and volunteers were loading ice and drinks into an ambulance. WIth no survivors to be treated, it had been turned into a refreshment truck for the workers at Ground Zero.

Throughout the lower Village, there were signs posted on trees and lampposts with photos and descriptions of loved ones that are missing. One man worked on the 100th floor, another on the 104th.

Newspapers were sold out everywhere.

On my corner of Sixth Avenue, a lamppost had been turned into a shrine, covered with posters of the missing, American flags, poems, notes and drawings, and surrounded by bouquets of flowers and flickering votive candles. A crowd had gathered at the intersection, some with American flags, and every time an ash-covered ambulance, fire, or rescue truck drove up from the disaster site there was cheering, applause and flag waving.

South of Houston was another lockdown zone, so Julie had to show her ID and vouch for me to get us past the barricades. Residents were still walking about and restaurants were open, but things got quieter and quieter as we walked down closer to Canal Street. Along the way, we passed a fire station crowded with buckets and buckets of fresh flowers, the firefighters standing around looking shell-shocked, and we wondered how many that station had lost.

After we stopped off at Julie’s apartment on the Bowery, we headed back west, and walked down Mulberry Street, through the heart of Little Italy, usually a bustling tourist trap. But at about 8:30 Wednesday night, the street was dark and dead. Three or four of the probably 50 restaurants were open, serving locals for once. Through the plate glass window of another restaurant I could see two older men, probably the owners, sitting in the dark, deserted dining room, their faces dimly lit by the flickering TV above the bar. One restaurant had erected a front wall of two-by-fours and chicken wire in anticipation of looters.

Canal Street really did look and smell like a war zone. It was almost entirely empty, except for the cops lining every intersection and the huge dump trucks full of debris lumbering east, away from Ground Zero. The street was covered in ash left from all the trucks that had been at the disaster site and there was the acrid odor of the fire. Some firefighters, cops, and emergency workers had come up from Ground Zero for a break, it looked like, and they were sitting on steps and on the sidewalk. They seemed shell-shocked and lonely, thrilled to see civilians. Above the buildings there was, chillingly, a huge billboard for Collateral Damage, in which Arnold Schwarzenegger plays a firefighter out for revenge after his wife and kids are killed in a terrorist attack.

Julie and I turned up Sixth Avenue towards my apartment. From Canal Street all the way to the barricades at Houston, it was lined with trucks and construction equipment. Many of the operators were standing on the deserted sidewalks by their vehicles, waiting for orders. Some were napping in the cabs.

The crowd at my corner, Sixth and Houston, was still gathered, with even more flags, cheering as trucks and workers exited the SoHo lockdown zone. Half a block up, though, stylishly dressed diners were lingering over wine and pasta at the cafe tables outside Da Silvano’s and Bar Pitti.

The wind had changed direction and was starting to blow acrid smoke up the West Side of Manhattan. We both decided we’d better spend the night uptown again and we caught the subway at West Fourth. Uptown the air quality wasn’t any better, though. Looking between the buildings, you could see the sky was thick and black. Arlyn’s doorman greeted us from behind an allergy mask. We kept the windows closed and the air conditioning off, and in a few hours the wind had shifted again.

Thursday night, Arlyn came home very early from work after a Time Inc. building bomb-scare evacuation, one of dozens across the city that day. She and Julie went out to a movie and I headed home to the Village. I had my overnight bag in one hand and Ripley’s leash in the other. We went into the subway at Columbus Circle and got apprehended by one of the six cops standing guard at that one entrance. “Ma’am, you can’t have the dog in here.” I explained I lived on Houston Street and needed to get home. “Well, you’ll have to take a cab,” he says. “What cab?” I ask—“They’re still blocking traffic at 14th Street. There’s no other way I can get down.” He was unmoved, and I decided not to argue. He was probably feeling as irrelevant as the rest of us, and having the opportunity to enforce a rule probably did him some good. So I took a cab down from 14th Street, showed my ID to get past the intersection, and walked home from there.

It was another bright, sunny afternoon and people were strolling up and down Seventh Avenue as they normally do, but normal doesn’t usually involve seeing small groups of guys chatting as they walk uptown, gas masks hanging casually from their belt loops. The wind had changed direction again and air quality became pretty bad as I got closer to home, with about one in ten pedestrians wearing an allergy mask or a bandanna. The weirdest part of it was the almost instant sense of normalcy. For the most part, no one looked scared or upset; they just put on a mask and continued about their business. I had to wonder if this was a preview of the future, once we bomb the Middle East and cause more terrorists to target New York.

The mobile command center was still set up at my intersection, and the lamppost shrine had expanded in circumference. I dropped off Ripley and went to try to volunteer, first at a church on Bleeker Street, two blocks up, then at a Red Cross shelter set up at a school two blocks west of me. Both places said there wasn’t an immediate need, so I left my name and number on the long signup lists both places and went home and looked out at the huge military helicopters circling downtown, breathing through my silk long underwear for lack of a bandanna. The World Trade Center was still missing from the skyline, and in my head I kept hearing, absurdly, in the soft, stunned voice of Rudolph the Red-nosed Reindeer from right after Yukon Cornelius falls over the cliff: “It’s gone! Oh, it’s gone!”

The church said there might be a need for people to work the overnight shift, bringing food to workers, so I planned on that. But with nothing better to do for the moment, I set off for my salsa lesson in Chelsea. My friend Jane normally joins me, but she’s the news editor for Businessweek and was exhausted and shell-shocked from watching the devastation out her office window and pulling together an entirely new front section in a day and a half. So I got our incredibly handsome young gay instructor to myself for an hour.

Both of us just needed to have some fun, so he led me for a while in all sorts of complicated moves, then we took turns leading and following as an older couple watched agape at our unexpected dissolution of gender roles. We quickly became drenched with sweat, since the windows were closed and the studio’s A/C was off to keep out the smoke and dust. Between the focus it took to continually switch roles and the sensual pleasure of the music and movement and touch, I felt a million times better afterwards. The best I’d felt since Monday.

I went over to Jane’s afterwards and listened to her war stories, then she and I walked down to meet Katie for a drink at Union Square, and to see the huge shrine that was set up there. By the time we got there the plaza was completely packed, with some people somber and reflective before the hundreds of candles and handwritten posters and art, others dancing barefoot to live drums and singing “Give Peace a Chance.”

On my way home at midnight, I stopped by the church and was told there was no more need for food or volunteers—the precincts had told them they were overwhelmed with supplies. A restaurant had just donated 60 portions of hot pasta pomodoro in takeout containers, though, and they were wondering what to do with it. I said I’d been on Canal Street the night before and there were groups of cops and workers and no food in sight, so maybe those folks, who are away from the main service areas, would want it. Four young guys had arrived to volunteer when I had, so we each grabbed a shopping bag full of pasta and a pack of Gatorade and headed for Canal Street. We had no forks, so we first stopped off at the pizzeria on the corner and asked if they’d donate some. The two Arab American workers there reacted almost as if we’d held them at gunpoint, nervously thrusting handfuls of plastic forks over the counter. It was depressing.

As we walked down Seventh Avenue we were joined by a young doctor in scrubs, stethoscope around his neck, headed for Ground Zero. He flagged down an ambulance and hopped in the back. It’s been like that all week, workers walking back and forth. Down at Canal, we walked the barricades and found piles of water, juice and snacks at each intersection. Most of the cops and workers said thanks but no thanks. A couple cops took homemade peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwiches that one of us had brought from the church’s endless supply. At one barricade we saw two pretty young women with a bicycle, serving hot coffee and pastries out of the wicker bike basket, which was lined with a red-and-white-checked cloth. Needless to say, they were more popular than we were. Finally, at a crowded break area on Church Street, we got some enthusiasm for the pasta and dropped it off, though I suspected the cops and military police and firefighters were accepting it partly to be kind to us.

By that time the sky was flashing from the imminent electrical storm, so I walked home, walked the dog, and went to bed, looking out at the dark skyline punctuated by huge bolts of lightning and the eerie white smoke rising from the disaster site, lit up by powerful work lights. I knew the bad weather would hamper the rescue effort, but it seemed more fitting to the circumstances than the obscenely bright, cloudless blue-sky days we’d been having. The temperature dropped and it started to pour and I thought about all the guys working in the cold and wet as I fell asleep in my warm bed.

By Friday the barricades were down at 14th and Houston, and the American flags had proliferated to the point where the Village started to look like a small town on the Fourth of July. At first it was frightening to see cars speeding by with flags taped to their antennae, associating that kind of patriotism as I do with gun-toting white supremacists. But then I realized how encouraging that sight must be for the morale of the rescue workers, and I started to feel glad that the flag had been reclaimed from the bigots.

The mood had become a little more somber as the reality of the devastation started to really sink in. It’s hard to walk around the neighborhood without crying. Everywhere you turn there are reminders of the tragedy. The trucks full of workers or debris are still passing by constantly, as they will be for weeks, I’m sure. There are shrines everywhere, and posters of the missing taped to trees, lampposts and bus shelters by desperate family members. Some of them I’ve seen so many times I feel like I must have known these people. I certainly know more intimate details about some of them than I know about my friends. Paula Morales from the 100th floor was just an inch shorter than me, and had a tiny heart tattooed on her right hand, between her thumb and forefinger. Mark Raswiler, looking kindly with a gray beard and glasses, beams at me from every other tree. He had blue eyes and weighed 185 pounds. Dick Morgan was 6’2” and wore a Swiss Army watch. I know he had a titanium hip, and his back was scarred from skin cancers that had been removed. It’s hard to see their faces every day, but getting to know them and grieving for them gives me a way to understand and process the tragedy. There’s no way I could process the fact that over 5,000 others died with them.

Going by the fire station around the corner, now that it’s no longer cordoned off, is the hardest. The shrine out front gets bigger every day. There are flowers, candles, posters, and banners from schoolchildren, and the names and photos of the 11 men they lost Tuesday morning. I didn’t know any of them personally, but I know I’ve said hello countless times as I’ve walked the dog past their station, and I know I watched them die.

The other quiet daily horror is the fear on the faces of the Arab Americans here. My corner store is owned by Arab immigrants, and they have been completely on edge. I saw another Arab American walking down Sixth Avenue with his head down, an American flag hanging from his shirt pocket like a white flag of surrender or a Nazi yellow star. I took a cab downtown late last night, driven by a guy named Mohammed Islam who was heart-wrenchingly friendly and courteous.

It’s also bizarre to see groups of New Yorkers, who normally wouldn’t bat an eyelid at the most shocking of sights, stop in their tracks on the sidewalk and crane their heads upward every time an airplane passes. Just two weeks ago I was on a subway car with a well-dressed, well-spoken lunatic who was raving loudly about CIA plots and the evil of women and the good of bombs and how Ted Kaczynski had the right idea, he just had the wrong technology—and no one paid him any mind at all.

On Saturday I had dim sum in Chinatown with Arlyn, Jane, and Rose—the first time I’ve ever not had to wait in a huge line for a table. Rose told us some of what she’d seen, as one of the first journalists to arrive downtown after the first plane hit. She’d gotten up to someone’s apartment on a top floor two blocks away, and was calling in reports to CNN via cell phone as she watched the devastation. A group of people stood bare-chested at the window on one floor, waving their shirts in a futile attempt to summon help. Another group stood and conferred, then, after a few moments, one man pushed his colleagues out one by one, then jumped himself. Apparently they’d all made the decision, but no one could do it. Then the tower collapsed. The stranger whose apartment she was in threw her the keys and ran out. When Rose contacted his wife later that evening, it turned out he was missing. All they can figure is that maybe, in the pandemonium, he ran the wrong way, into the second collapse.

After brunch, we walked further downtown, past occasional smashed cars and crumpled Con Ed trucks turned into shrines, to the edge of the Frozen Zone, where the sidewalk was clogged with journalists, cameras, and satellite dishes, and the street lined with fire trucks and SUVs filled with Gatorade and huge bags of dog food. Just inside the zone, a massive McDonald’s truck was serving workers, with portable golden arches erected on a tall pole above the trailer for the benefit of the cameras. Clearly visible just five blocks down was the smoking pile of Ground Zero, two- and three-story shards of the Twin Towers’ outer shell recognizable in the rubble. Rose, perhaps as a way to deal with what she’d seen, was the Julie McCoy of our disaster tour, pointing out the sites and telling us which heap had been which building, and giving us the background information and gory details. A group on the sidewalk clapped and cheered as several ash-covered firemen walked up from Ground Zero. Once again, it was a gorgeous day, and, even more disorienting, the sidewalks and streets were practically sparkling. There were traces of the collapse in the ash still clinging to windows and awnings, but Thursday night’s downpour had swept most of it away.

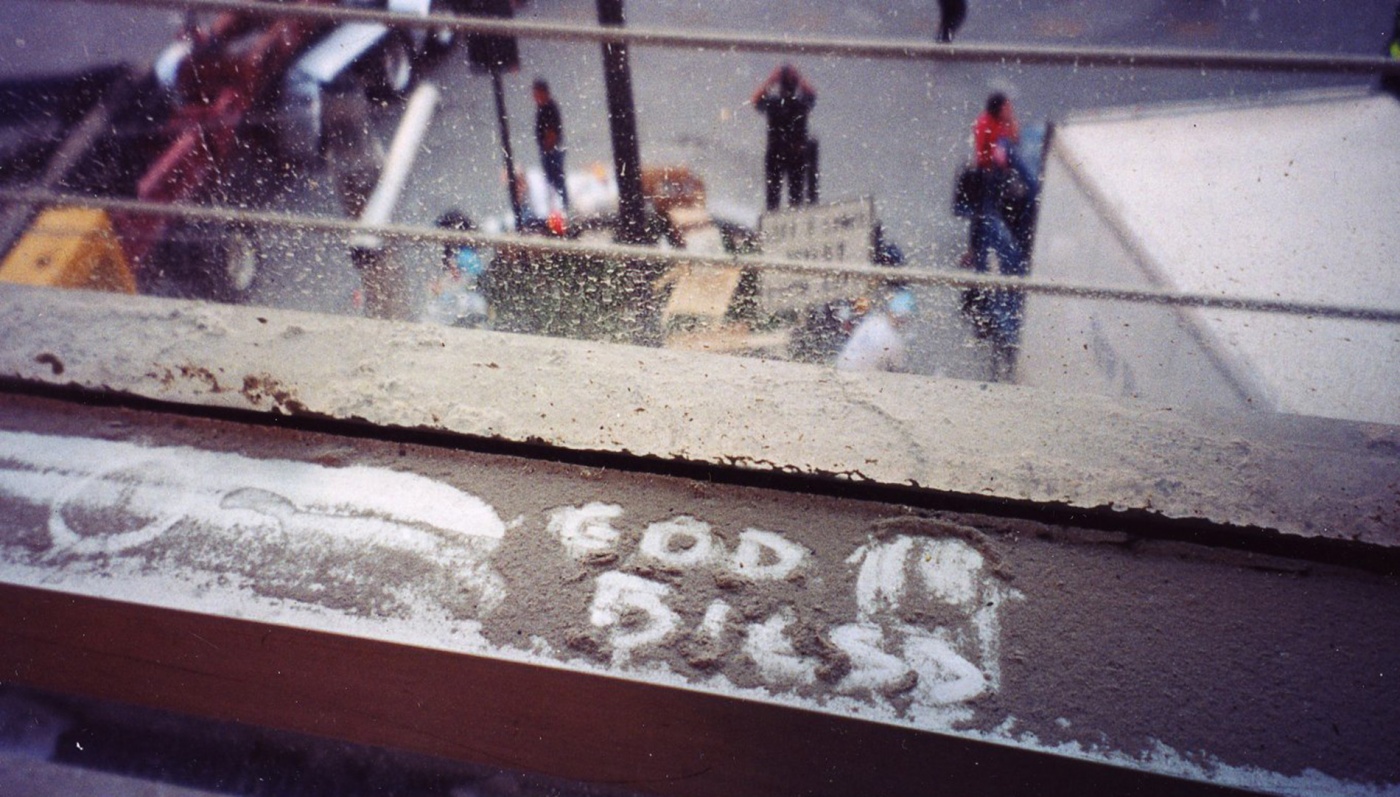

Walking further, we found ourselves on the West Side Highway, where I’m sure we were not supposed to be. Perhaps the cop saw Rose’s press pass and figured we were legit. From Houston Street to Chambers (at least a quarter-mile), the six-lane road had become a tent city, with construction supplies, cases and cases of bottled water and snacks, and volunteers dishing out hot meals to the workers. The atmosphere was calm and pleasant; more construction site than disaster zone. Closer to the Frozen Zone, there was an ASPCA trailer where they were washing and bandaging the paws of the rescue dogs. We saw a number of them, German Shepherds mostly, padding gingerly across the asphalt beside their trainers, their paws clearly sore from navigating rubble. At least a hundred men in hard hats and work clothes were amassed at the gate at Chambers Street, waiting to be allowed in to dig for survivors, or bodies. In the ash fallout in a pedestrian overpass just above Chambers, five blocks from the site and sheltered from Thursday’s cleansing rain, someone had scrawled, “God Bless.”

None of us could take it anymore and we started uptown. Mistaking us for workers of some kind, a volunteer who was heading south offered us all an “ice pop.” We all politely refused what would have been the Popsicles of Shame and skulked back where we belonged.

Now, for the most part, life goes on as usual here, though still a little quiet, a little somber. Saturday night, usually crowded and loud with drunken partiers, felt more like a Sunday. The candlelit, flower-strewn shrine in front of the firehouse has gotten so large it’s starting to block the sidewalk, and the votives around the intersection lamppost still flicker around the clock. And the night skyline still features the ghostly white cloud of backlit smoke and dust rising up from the space where the towers used to be.

New York has always seemed generally friendly to me, and I’ve always felt a sense of community, perhaps because I often have a dog with me, and maybe because my usually friendly, open attitude invites reciprocation. But since the attack, this part of the Village has become much more of a small town, with strangers making eye contact, saying hello on the sidewalks, and being especially polite, as if somehow that will soften the blow. It’s a nice change, on the one hand, but I find myself yearning for the innocence and naivete of the brusqueness we lost last week.

Louise Sloan ’88 is the editorial content director of the BAM.