Brave Enough to Be It

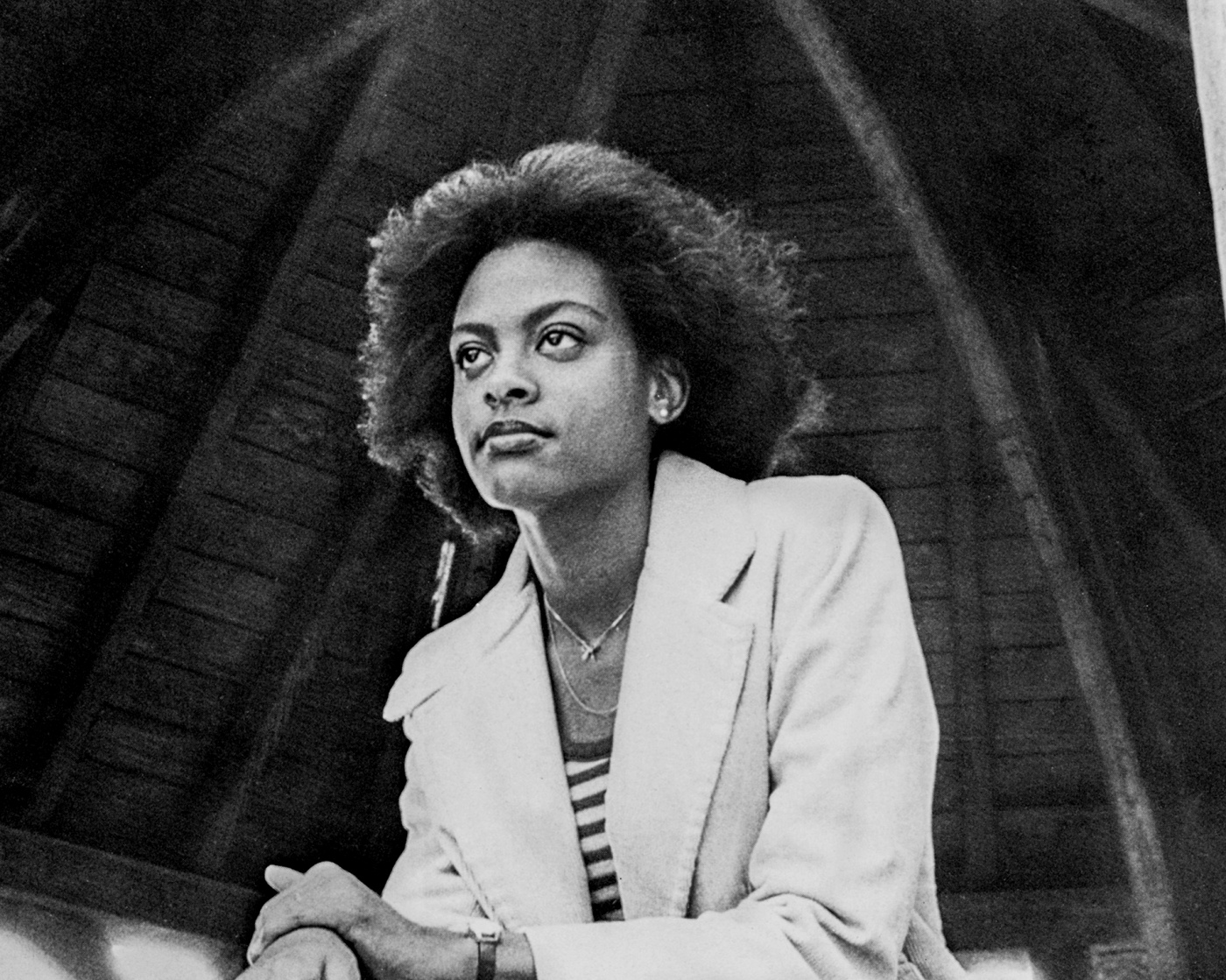

“Women can’t be priests.” “A Black person can’t lead a white church.” “There’s no way you’re getting into Brown.” Bishop Paula Clark ’84 pushed her way past all the closed doors—and aims to open them even further.

One week after the murder of George Floyd, Rev. Canon Paula Clark ’84 was standing on the portico of St. John’s Episcopal Church, leading informal prayer groups and passing out water and snacks to Black Lives Matter protesters gathered in Lafayette Square across from the White House. All day long, the protests had been peaceful. But by late afternoon the atmosphere turned menacing as National Guard troops began to pour into the streets. “It was not feeling very safe,” Clark recalls. She was joined by her daughter, Micha, a journalist covering the protest. “We saw the tanks coming as we were leaving.”

What Clark didn’t know at the time was that the Guard troops were preparing to clear the route for President Trump to make his now infamous walk across Pennsylvania Avenue to pose in front of historic St. John’s, which for two centuries has been known as “the Church of the presidents.” Mayhem ensued as troops pushed clergy off the portico and protestors dove for cover, thinking the tear gas explosions were grenades. Smoke filled the square. “It was awful and it was intentional,” Clark says. Nearly a year later, the fury burns as she recalls attempts to return to the church the following day.

“We were back, but we were blocked from St. John’s,” Clark remembers. “The federal government blocked the bishop of Washington, priests of Washington, and clergy of St. John’s Church entry to their church.

“They blocked our entry to our church,” she says, still incredulous.

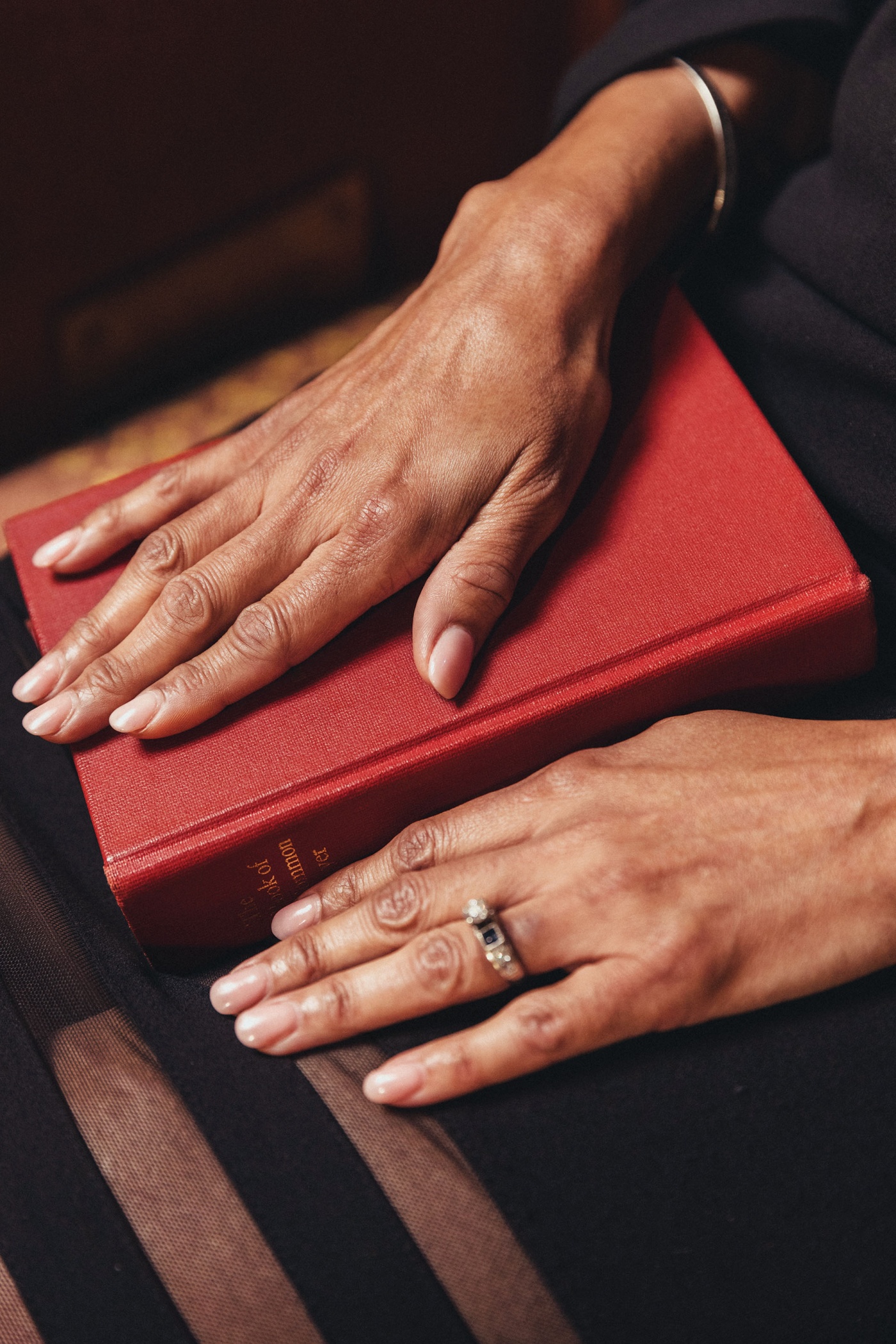

Then there was the image of Trump waving the upside-down Bible in front of the church’s sign board. “It made a mockery of our holy scriptures for a photo op,” she says. “I was insulted by it. To clear the people of God prayerfully present and protesting for a photo op was unconscionable.”

The experience took Clark back to 1968, when she was six years old and Washington D.C. was on fire.

The city had erupted in violence after Martin Luther King’s assassination and the National Guard had been dispatched to Clark’s mostly Black middle-class neighborhood in the southeast quadrant of the city, overlooking downtown Washington. Only there was no violence in Hillcrest. Clark recalls her father loading the family in the car to go rescue her godparents in another part of town and take them back to their quiet neighborhood.

“I remember my mother saying ‘it’s important that you remember this,’” she says. “That was my déjà vu there on Lafayette Square last year,” Clark says. “These were peaceful persons on whom the full force of the federal government was unleashed.”

Clark is carrying that fierce sense of righteousness with her as she moves halfway across the country to become the 13th Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Chicago, the first African American and first woman elected to lead the diocese in its 186-year history. Her consecration has been pushed back several times since April, when Clark suffered a cerebral bleed while exercising two weeks before the big day. At press time—late July—Clark was recovering well from brain surgery but a new date for the consecration has yet to be set.* She says she feels she has come full circle, growing up at the end of the 20th century’s civil rights era and ascending to one of the highest positions in the Episcopal church during the Black Lives Matter movement.

Conjuring an inclusive God

Racism propelled Clark to the Episcopal church. Clark’s parents moved to D.C. in the mid-1950s after her father, Willie Clark, a Korean War veteran, was recruited by the Census Bureau for his math skills to work on the first generation of computers. They settled in the Hillcrest neighborhood, which at that time was a virtually all-white community, full of federal workers living in tidy Tudor Revival homes with expansive lawns.

There was no welcome wagon for the Clark family. Seared in her memory is the time a neighbor hurled the n-word at her as her mother wheeled her down the street in her stroller. “It was traumatizing,” she says. Then there were the times clerks were hostile to her family in downtown department stores. “They treated us horribly,” Clark recalls.

Sundays were no different. In fact, an incident at the Clarks’ Baptist church would become a defining moment in Clark’s life. Her family attended the predominantly white Baptist church until it became clear that there was no place for Black congregants as church lay leaders. “My father picked me up from the pew and we left,” she says. They never returned.

White flight to the suburbs happened soon after. The new wave of Hillcrest residents were members of Washington’s Black intelligentsia, college educated professionals. They formed their own faith group: The Fellowship of the Free. Welcomed by the local Episcopal church, St. Timothy’s, they were given access to a basement meeting room to celebrate communion every Friday. It was there that the outlines of Clark’s ministry today began to form.

“I developed the idea of church not as an edifice but as a place where there is any gathering of the people of God,” says Clark. “Not only the pastor in the pulpit. It was my idea of what the church ought to be. The kingdom of heaven was multicultural and multiracial.”

The fellowship dissolved after a while. “We couldn’t live on love alone,” she says.

For a short time, the family returned to the Baptist church, this time an African American congregation downtown, where endless services were the norm and little girls were expected to wear itch-inducing crinoline fabric dresses.

“Paula knows how to mobilize congregations and the community. She loves working with people, mentoring. She has a pastoral heart. I knew she’d be a bishop one day.”

At age 10 Clark returned to St. Timothy’s alone, walking the block and a half to the church without her parents. She was drawn in by the folk masses, “where you could wear jeans and Wallabees” and sing songs of love, peace, and protest. Paula breaks into song as she looks back:

I got a hammer

And I’ve got a bell

And I’ve got a song to sing

All over this land

It’s the hammer of justice

It’s the bell of freedom

It’s the song about love between

My brothers and my sisters

All over this land

“That’s how I became an Episcopalian,” Clark says.

Clark was baptized and confirmed at age 10 by the Bishop of Washington, John Walker, the first Black bishop of the diocese, who would become a giant on the world stage advocating for civil rights and social justice. “I was intoxicated by his voice,” she says. “He could conjure God.”

After Clark graduated from her public elementary school, Walker directed her parents to send her to the National Cathedral School (NCS), an all-girls prep school on the grounds of the Washington National Cathedral. “The Cathedral meant nothing to me,” she says. Located across the city in the white enclave of Cleveland Park, NCS educated daughters of Washington’s power elite—from presidents and members of Congress to diplomats and partners in top law firms. Clark recalls the woman administering the application test being astonished she finished so fast. She was admitted.

Bus-riding past power

For six years Clark rode the public bus two and a half or more hours a day from the far southeast corner of the city to its upper northwest quadrant. The route wove through downtown, past the Capitol, the Supreme Court, and the White House.

Decades later, reading Michelle Obama’s passages about her childhood riding the city bus in Chicago in her memoir Becoming touched Clark. “Riding past the places of power, and how that impacted who she was,” said Clark, “reading that in the book, I wept. That was absolutely my experience. I passed the seat of our nation’s power.”

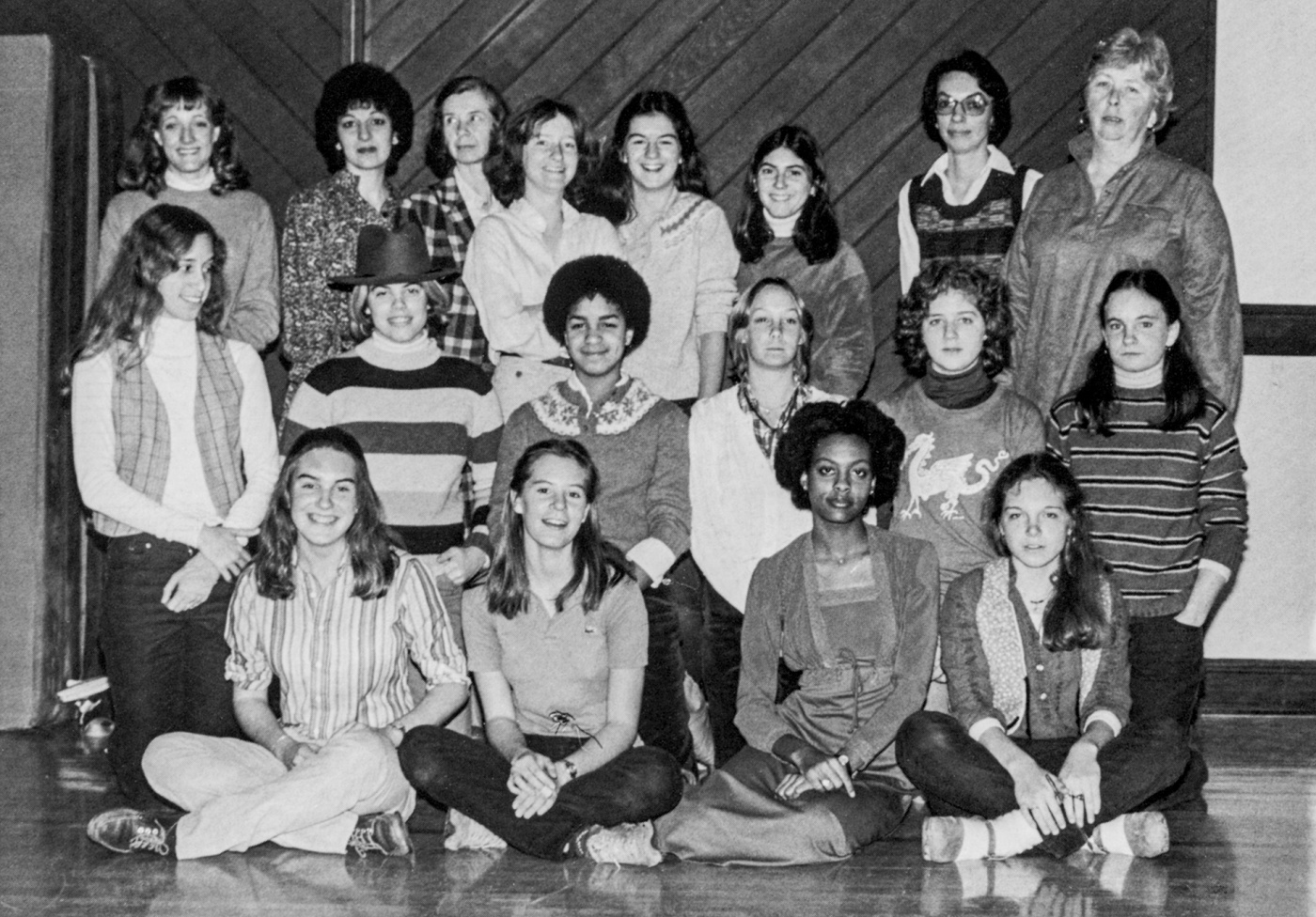

Some of her white classmates, like me, hopped on the same bus for the ten-minute ride up Mt. St. Alban to the Cathedral close. Paula’s lengthy commute was not lost on me as a teenager. I knew she’d traveled a long way, but Hillcrest was a name on the bus; I had no reference point for the duration of her commute, her community, or her struggles with discrimination as one of six African American girls in our class of 60.

“In the language of today it would be extensive microaggressions—and underestimation,” Paula says. “The expectation among the teachers and certainly students was that I would not perform.” She shared the story of our 8th grade English teacher pulling her aside after class one day and accused her of plagiarizing (“My mother went ballistic,” she recalls) and of enduring the pain of knowing school activities and social events at area country clubs were not open to Black students.

Those were not the only closed doors to contend with. At one of our Friday morning services in the cathedral in 1975 a female priest delivered the sermon—only there weren’t any women priests in the Episcopal church at the time, officially speaking. The priest was one of the now famous “Washington Five,” women deacons who had been ordained “irregularly” in defiance of church custom.

“Now we are having services in people’s backyards—gatherings of people of God in community. I was talking about that 20 years ago—that we don’t have to have stained glass to be church.”

“That particular sermon had an effect on me,” says Paula, who was 13 at the time. “I knew unequivocally that I was called to the priesthood despite the fact that women were not ordained in the church.” (That would change in 1976.) “I went home and told my mother,” Paula adds. “She said, ‘I don’t believe in women’s ordination.’”

“What if I did it anyway?” Paula asked. Her mother replied, “I would not attend your ordination.” Paula set her calling aside, or at least pushed it to the back of her mind for 25 years. “You bury it; you try to go on with your life, but that’s the problem with the call, it never goes away.”

Paula plunged herself into Bible study and spent her weekends at St. Timothy’s Church—the neighborhood Episcopal church that had opened the basement to her family years earlier. “I love church. I fell in love with scripture. I was a real church rat,” she says. “My weekend side hustle was to clean the church. It was holy work and I loved it.”

She sought to walk in the footsteps of her spiritual mentor, Bishop Walker. “He cared deeply about the city and was able to accomplish so much by sheer passion,” she says. “He used his authority and power for the good of the people. It’s the reason I model my ministry after his.”

At the National Cathedral School, Clark says, “the college guidance counselor told me I’d never get into Brown. I got in early admission.” Once on campus, she studied sociology and soaked up knowledge from fellow students. “Who I am as a Christian was formed there. The people who had the most influence on me were my fellow brother and sister students at Brown,” Clark says.

She attended “Black chapel,” sang in two gospel choirs, and participated in Romans 8, a prayer group. She joined protests against apartheid, undergoing an awakening about global civil rights and social justice. And she pledged Alpha Kappa Alpha sorority, embracing its commitment to service and education. “It’s still a part of who I am—empowering and uplifting women,” she says. Clark wrote her thesis on stereotypes of Black women in the workforce. “It informs who I am as a leader today,” she says. “How despite obstacles Black women excelled.”

After receiving a master’s degree in public policy at University of UC Berkeley, she returned to D.C. to work in the Office of the Mayor of Washington, D.C. Among her duties was handling communications in the parole department at the height of the crack epidemic. Her Monday morning ritual was combing through a two-inch stack of faxes from the police department on the drug-related homicides that had occurred over the weekend.

It was the era of mandatory minimum sentences and three strikes laws and racial disparity in drug sentences—all against the background of what she described as “punitive” oversight by Congress and the outsourcing of district offenders to federal prisons. “We talk about the school-to-prison pipeline. I saw that up close and personal,” she says. “Disproportionate sentencing of women. It’s had a lasting effect.”

Heeding God’s call

Before her death from brain cancer in 1999, Clark’s mother, Constance, did at last express her support for her daughter’s ordination. It was the affirmation Clark needed to again begin thinking seriously about the priesthood. “The impetus was, life is short,” she recalls thinking. “If you are to be a priest, life is not promised.” At 39, she enrolled in the Virginia Theological Seminary, which had been integrated by John Walker 50 years earlier.

After her ordination in 2005, Clark moved up through the ranks in the Diocese of Washington, serving as an associate rector and then rector at two area churches before becoming a canon and head of development for multicultural ministries focusing on African American and Spanish-speaking congregations and helping parishes in transition. She would later be promoted to “canon to the ordinary,” the bishop’s top aide and chief of staff.

“Her background was suited for the diocese,” says Mariann Budde, Bishop of Washington, ticking off Clark’s lifetime association with the diocese and leadership roles in the church and in city government. “She knows how to mobilize congregations and the community. She loves working with people, mentoring. She has a pastoral heart. I knew she’d be a bishop one day.”

In the last year, Clark has led efforts to address what she described as the “dual pandemics” of COVID and racism, expanding the D.C. diocese’s antiracism training and awareness programs and setting up a COVID relief fund that helped 800 congregants, even as she was embarking on a new journey. In late 2019 she slipped in under the wire to apply for the opening as Bishop of Chicago, beginning an arduous, year-long selection process. “It sounds corny but I felt called by God, that God was calling me to it as much as running away from it,” she said. When she saw the final slate of four candidates, she knew she had made the right decision. “The final slate was all people of color—that was stunning and encouraging. I knew I wanted to be part of this brave diocese,” Paula says.

The Chicago Diocese, the tenth largest in the nation, with 122 churches, occupies a much larger footprint than the Washington Diocese—it stretches 200 miles from the Wisconsin border to south central Illinois. Clark will become the spiritual leader for a wide array of churches, each facing their individual issues: declining numbers of congregants, struggling to keep the lights on, churches in Chicago communities with rampant gun violence and churches in rural corners dealing with the opioid crisis. Add to that the diocese as a whole—like church communities everywhere—facing foundational change brought about by the pandemic.

“I will challenge the status quo. Not all together and not all at once. I’m not an in-your-face kind of person,” says Clark. “That’s where Bishop Walker kicks in—the ability to stand up for what is right and good for all people.”

Envisioning the future of the church in a post-COVID world, Clark says, has allowed her to explore the vision of ministry she imagined in the basement at St. Timothy’s Church. “The notion of planting churches, the notion of a house church, was foreign for the Episcopal church even a year ago,” she says. “Now we are having services in people’s backyards—gatherings of people of God in community. I was talking about that 20 years ago—that we don’t have to have stained glass to be church.”

“I want to spread love of God far and wide among God’s people,” she adds. “I want everybody at the table and I want us to transform this world.”

As she settles into her new home at the Bishop’s Residence on the north side of Chicago, Clark carries with her that righteous anger of June 1, 2020, when armed troops let loose their fury on a crowd of peaceful protestors outside her church—the nation’s church. “I think the events of June 1 showed that we as a nation have awakened to the seriousness of racism in this country,” she says. “We need to speak out against it and we have to be brave enough to do it.”

She pauses to ponder the mission statement of the Diocese of Chicago: Grow the church. Form the faithful. Change the world. “I may flip that to change the world first, while meeting the needs of the current world. I think of the last lines of [Youth Poet Laureate] Amanda Gorman’s inauguration poem:

For there is always light,

if only we’re brave enough to see it

If only we’re brave enough to be it

Clark pauses. “Being a bearer of light matters most to me right now.”

*Paula Clark's consecration was delayed once more in August to allow her more time to recover.

*Update 9/19/22: Bishop Paula Clark was consecrated on September 17, 2022. Read more here.

Amy Worden is a former reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer and current contributor to the Washington Post. She and Bishop Clark were classmates at National Cathedral School in Washington, D.C.