Beloved

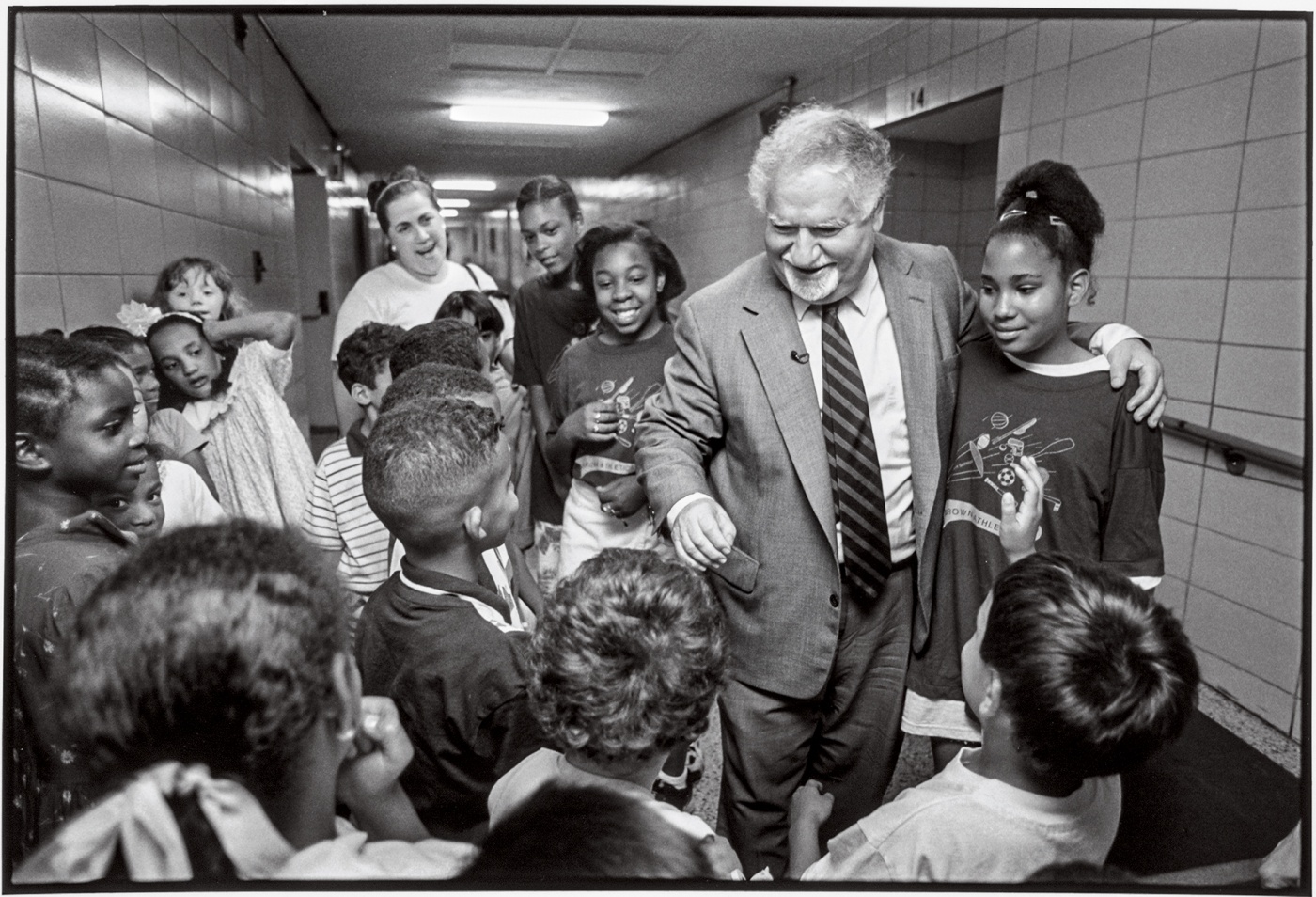

Former President Vartan Gregorian, who transformed the N.Y. Public Library, then Brown, is perhaps most remembered for his generous spirit—and bear hugs.

“You are a unique moment in the history of creation,” Vartan Gregorian told incoming freshman classes every year of his Brown presidency. “You have to decide what you want to do with your uniqueness. You can be a dot, a letter, a word, a sentence. You can be a paragraph, a page, a chapter, a book….”

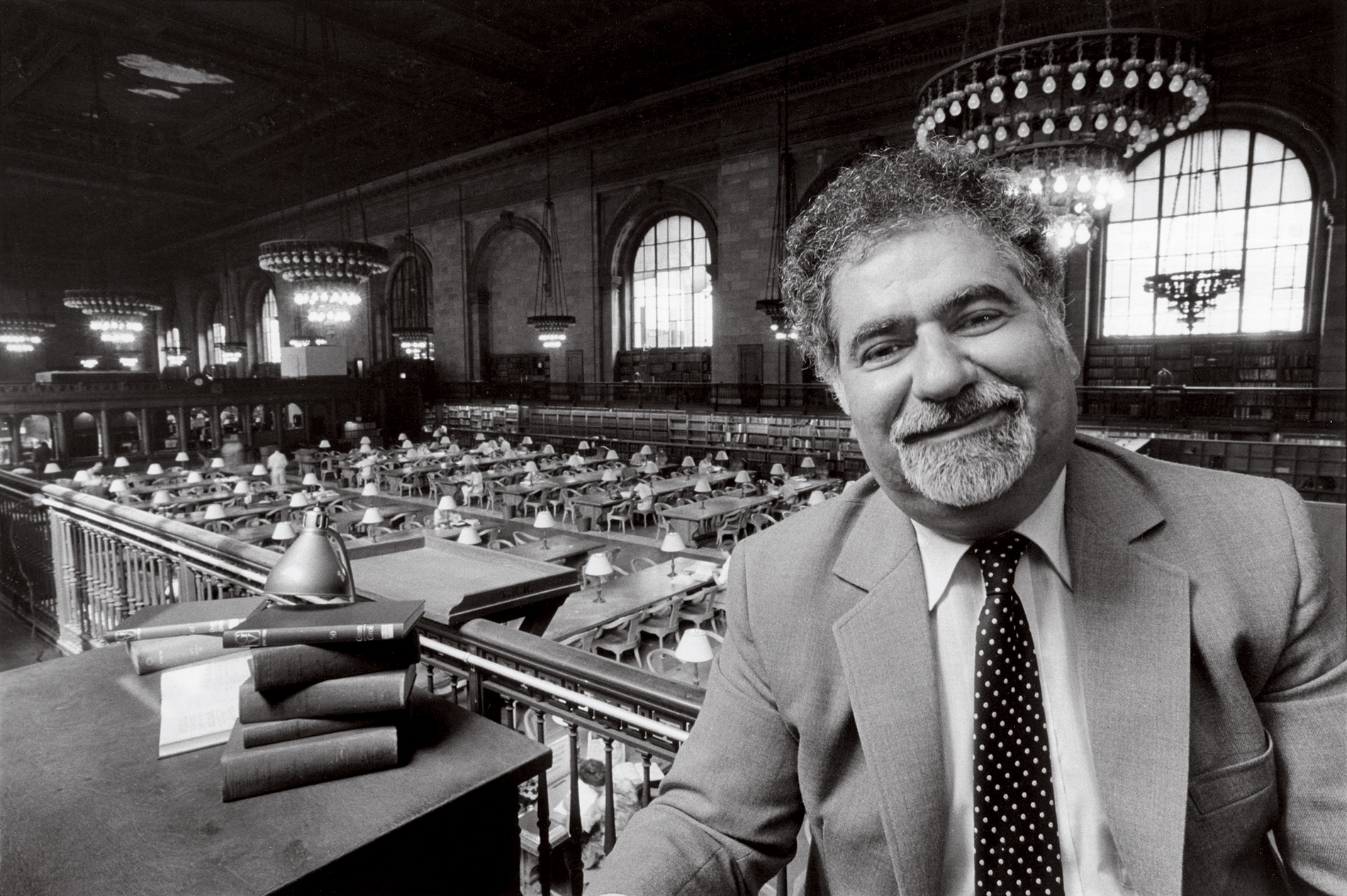

Gregorian passed away in mid-April at 87, but his own life was at least a book, epic and sprawling and full of vibrant prose. As much as his legacy can be measured in robust and distinctive chapters—among them his legendary transformation of the New York Public Library in the ’80s, overseeing the globalization of Brown in the ’90s as president, and his final two decades heading the Carnegie Corporation—the merit of the man can be found in the everyday encounters that gave his life lyricism.

He doled out spontaneous bear hugs in the Ratty, went for drinks with the University’s custodial staff, and whenever he handed out his business card to people he just met and told them to call him later, he meant it. Part of his charm included his habit of dropping articles of speech—of the seven languages he knew, he said he had the least command of English.

Gregorian could barely make it across the Main Green during the heyday of his presidency, which lasted from 1989 to 1997. “Honestly, it seemed like every five steps, somebody was stopping him,” says Anne Hinman Diffily ’73, former editor of the Brown Alumni Magazine. “He was a celebrity.” But no matter how much fame, power, and influence he held over the course of his career, Gregorian remained truly humble from start to finish, longtime friend and former University legal counsel Beverly Ledbetter says.

After his mother died young, Gregorian was raised by his grandmother Voski in Tabriz, Iran. A soulful, illiterate Armenian woman, Gregorian’s grandmother impressed upon him the value of education and integrity, filling his head with colorful aphorisms that would guide him in life, he wrote in his autobiography, The Road to Home. Two examples: “Don’t envy, you must not have a hole in your eye” and “What endures are good deeds and reputation, one’s name, one’s dignity.”

Against the odds of an oppressive bureaucracy and the family’s lack of means, Gregorian secured the necessary permissions to attend high school in Beirut—with his grandmother urging him on, even when his father at first told him to stay home. Gregorian enrolled as an undergraduate at Stanford University in 1956, arriving on campus “with a rudimentary grasp of English and complete ignorance of American society,” he recounted in a 2006 commencement address at his alma mater.

At Stanford he met Clare Russell, the tall and dignified woman he would marry. After graduation the two journeyed across the Atlantic, where Clare would settle in Beirut while Vartan spent months in Afghanistan researching his dissertation, “Traditionalism and Modernism in Islam.” (He also went on to write a renowned history of modern Afghanistan.)

“I think that was a little symbolic of what the adventure became, they just set sail,” says his son Vahé, one of Gregorian’s three children. “It always seemed open-ended to me, but he had a sense of mission about what he could do and could be in the world… that was always in his heartbeat.”

Gregorian served at half a dozen universities before coming to Brown, including six years as provost at the University of Pennsylvania before helming the ailing New York Public Library in 1981.

Gregorian had always loved the hushed promise of libraries, and he learned the history of every collection in the venerable but then-ramshackle New York institution. His commitment was so intense that when he first arrived he even tried his hand at the information desk, joking later to the New Yorker that the influx of calls and requests was “a terrifying experience.”

“He believed in the entire model, the entire theory, the entire idea of a liberal education.”

If anyone knew how to handle a full workload, though, it was Gregorian, who kept 14-hour workdays every day but Sunday (and this respite only at his wife’s insistence). He led a whirlwind of fundraisers and networking, delivering impassioned speeches in every corner of New York society. He was widely credited with rescuing the system from bankruptcy and restoring its status as an iconic New York institution integral to civic affairs.

But Gregorian longed to return to teaching and education, and Brown was on the lookout for a well-rounded president, says Martha Nussbaum, who headed the University’s search committee. “Gregorian stood out for his academic distinction, his proven administrative and fundraising ability, and his ebullient and affirmative personality.”

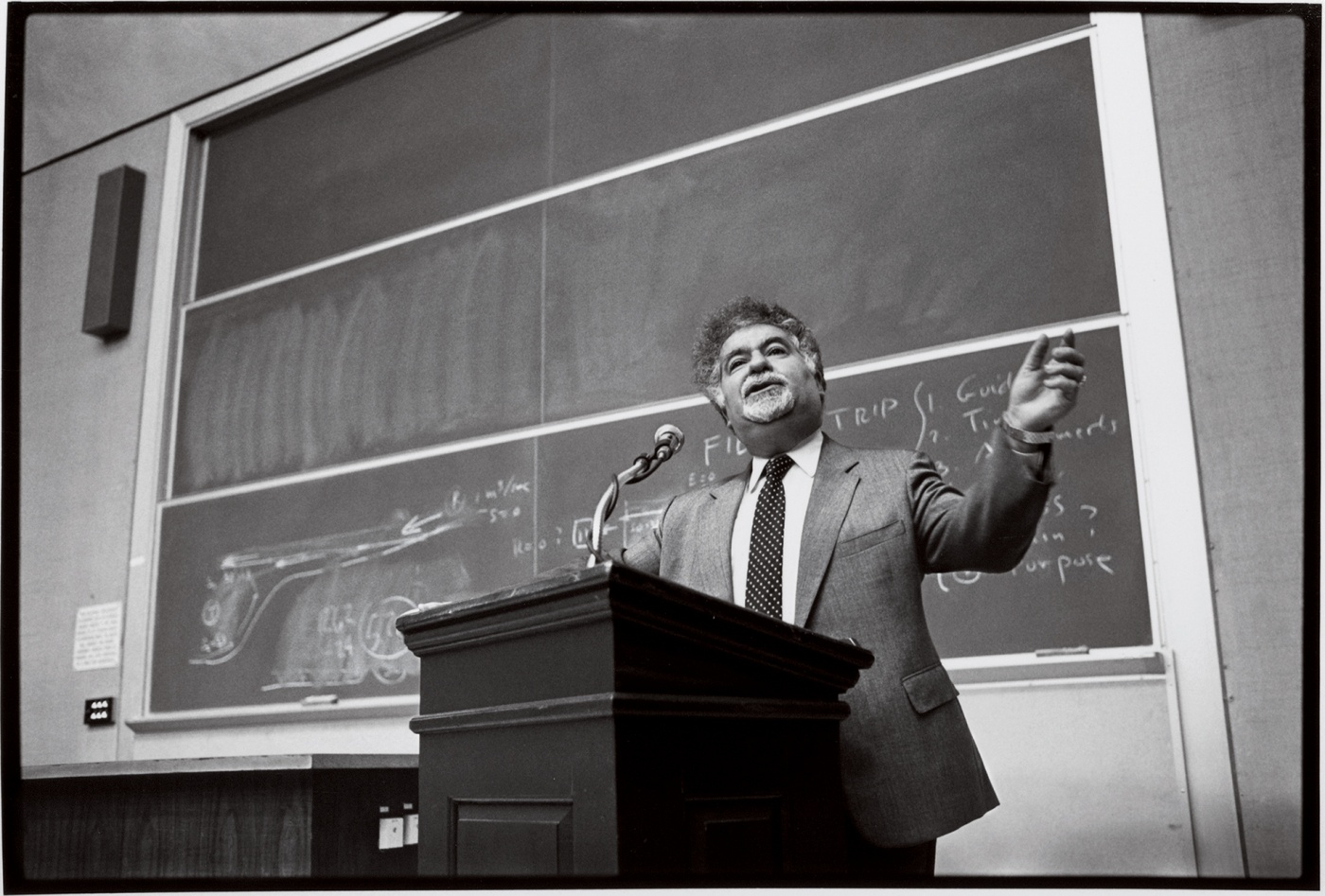

Arriving in 1989, Gregorian commissioned a study on the Open Curriculum that showed its approach was a resounding pedagogical success among students, then set about amplifying its strengths and opening up more opportunities for cross-disciplinary teaching and scholarship. “He believed in the entire model, the entire theory, the entire idea of a liberal education,” says biology professor Ken Miller ’70. Gregorian’s enthusiasm was contagious, and students loved him for it: “When Gregorian walked in, the class went nuts, screaming, yelling, whooping, standing, clapping,” Miller recalls of the President’s appearance at an intro to biology lecture class.

In fact, Gregorian made a point of teaching a class almost every year at Brown, including a freshman seminar on liberalism that former student Jacob Levy ’93 remembers as a transformative experience. Gregorian would always make time to sit and talk, Levy says, engaging with the rants of a moralistic 19-year-old.

“For someone of his stature and responsibilities to be taking that kind of time was really just extraordinary,” says Levy, now a political science professor at McGill. “And the longer I spend in a university environment, the more I understand how extraordinary it was.”

Gregorian wanted the best professors in the world at Brown, and set about endowing dozens of faculty chairs, including for the first time assistant professorships, in a bid to secure young talent; other reform efforts included “pausing the tenure clock” for new mothers.

With the cost of tuition steadily increasing, he sought to ensure that Brown remained accessible, and oversaw a marked increase in both the proportion of minority and international students and the financial aid available to them.

To deliver on this vision, Gregorian led the University in a five-year “Campaign for the Rising Generation,” ultimately yielding $543 million—the largest campaign to date, which more than doubled the University’s endowment. Growth followed, including libraries, labs, campus centers, and now iconic buildings such as the Watson Institute and the Annenberg Center. Gregorian also brought numerous renowned authors and intellectuals to campus, from Maya Angelou to Umberto Eco and Susan Sontag.

He applied his personal touch to interactions with students, too. Suzanne Rivera ’91, a former student activist with Students on Financial Aid, pushed the administration to do more to achieve fully need-blind admissions. Though she and Gregorian “butted heads’’ on many occasions, Rivera says he always greeted her warmly around campus, and after her graduation sent her a note reading “Dear Sue, I am very proud of you and I wish you the best of luck... You are a born leader.” Now president of Macalester College, Rivera has the letter framed in her office.

Gregorian honored the work of his staff at all levels, naming a building after Phil Andrews, a long-serving custodian. His affectionate spirit was a beacon. Former Interim President Sheila Blumstein, when working as a dean, would find herself checking if lights were on at 55 Power Street on her way home after working late. “When they were I kind of felt, ‘Oh, they’re home. I’m safe. It’s okay.’ I just had this feeling of comfort,” she says.

Gregorian returned to New York in 1997 to run the Carnegie Corporation, fueling nonprofit funding with the powerhouse foundation established by an immigrant who, like Gregorian, remade himself within the promise of America. His executive assistant Natasha Davids, another fellow immigrant (from Jamaica) worked alongside him for his entire tenure there, and remembers a boss who lovingly pushed her and those around him to accomplish things they didn’t believe they could.

And he kept giving out his card. One recipient was an Armenian cab driver Gregorian met during a commute in D.C., who asked if Gregorian could speak at his Armenian group next time he came back to town. A few months later, Gregorian did just that. Moments like these led Davids and the rest of the Carnegie office staff to realize, in the days after his passing, just how important “VG,” as they nicknamed him, had been—at Carnegie and far beyond, across the many passages of his life. “He was so much more than just us, he belonged to so many more people,” Davids says. “He had these wonderful stories and experiences and we had to let him go.”

Gregorian’s board memberships, fellowships, and humanitarian efforts would require another article. His many awards included the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the National Humanities Medal, France’s Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, Armenia’s Order of Honor, the Ellis Island Medal of Honor, and the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters’ Award for Distinguished Service to the Arts.

Gregorian’s wife, Clare Russell Gregorian, died April 28, 2018. He is survived by his three sons: Vahé Gregorian and his wife, Cindy Billhartz Gregorian; Raffi Gregorian; and Dareh Gregorian and his wife, Maggie Haberman Gregorian. He is also survived by five grandchildren—Juan, Maximus, Sophie, Miri, and Dashiell—and his sister, Ojik Arakelian.