I met Norman Boucher on his first day of what would be a 26-year stint at what was then called the Brown Alumni Monthly. It was November 1994, and he’d been hired as managing editor (he would become the BAM’s sixth editor and publisher four years later). At the time, the BAM offices shared the top floor of a palatial former home right next to Brown’s main green. “A bit like the servants’ quarters up here, isn’t it,” he said to me. It wasn’t a question. I nodded, not quite sure how to respond. He stared at me for a moment then stuffed his hands in his pockets and rolled his shoulders back, standing up a little straighter. “I have two questions,” he said. “Where’s the bathroom, and where can I get a cup of coffee?”

I was a young staffer at the magazine, responsible for administrative tasks and general gofering, and burning to be a writer. Norman was the real thing. He had been a freelancer for years, contributing to magazines like the Atlantic, the New Republic, the New York Times Magazine, Esquire, the Boston Globe Magazine, New Age, Audubon, and Wilderness, along with many others. He was the author of A Bird Lover’s Life List & Journal, published by Bulfinch Press at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. As a young scriptwriter for New Hampshire Public Television, he wrote the series The Franco File, which was awarded a regional Emmy for Best Children’s Program of 1979.

Norman and I worked together for seven years and grew familiar with each other’s strengths and weaknesses. We never got very good at the whole mentor-mentee thing, but he taught me more about writing than anyone else in my career. His approach to the labor of storytelling, of finding exactly the right words in exactly the right order, was devotional and infectious.

As an editor, Norman could argue for days on how to lead or structure a story, if a particular book should get reviewed, or whether I was being too soft on a subject in my description of his or her motivations. Or, rather, I argued with him after he had already made up his mind. Norman never lost the writer’s conviction that he could see things you couldn’t. He could see a story’s path in words the way a priest can see redemption or damnation in choices and actions—and Norman brought at least as much passion to his work as a priest does to the eucharist.

“Norman could see a story’s path in words the way a priest can see redemption or damnation in choices and actions.”

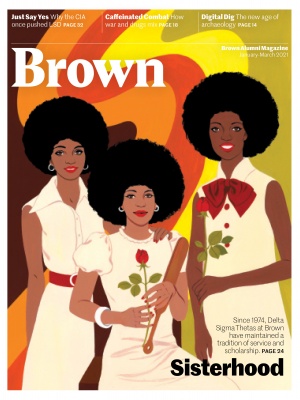

The BAM was a funny place for Norman to land. He never planned or expected to become the editor of an Ivy League alumni magazine; his ambitions lay first in the world of commercial publishing. But he was also passionately committed to helping the BAM succeed. When he retired in 2018, he told an interviewer that two things kept him up at night: not knowing with any precision how many BAMs go straight into the recycling bin and not knowing whether Brown alumni read anything beyond the Classes section. The way he came to live with this uncertainty was to commit to stewarding the distinctive BAM voice while upholding its high standards of reporting, factual accuracy, and fairness. Norman saw his role as bringing Brown to alumni in ways that are relevant to their lives today, ensuring every editorial choice was about the reader. If the BAM doesn’t get that right, he observed, “We’re cutting down a whole lot of trees for nothing.”

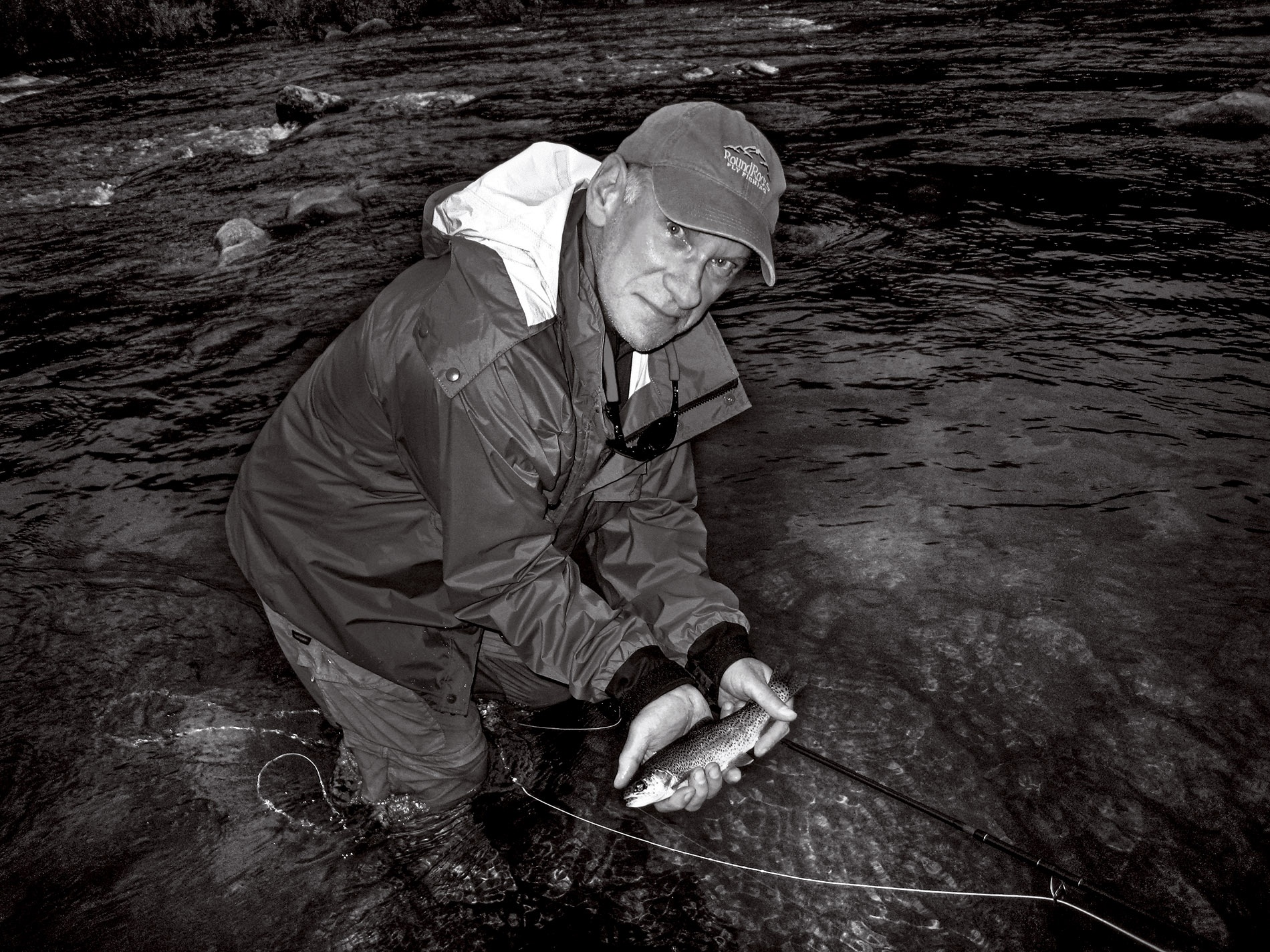

Norman’s origins were modest and very New England. His father Louis, whom he referred to (without irony) as the bodhisattva, sold shoes in Nashua, N.H. His sister Flo taught school. Norman had a deep, long-suffering love of the Red Sox and was in a multi-family season-tickets group for three decades. (He took me to one game and decided I was not sufficiently engaged to merit any further invitations.) He also had a profound love for the natural world; he traveled every December to Florida to paddle around the Everglades with his friend Neal, and spent countless lunch hours walking around College Hill identifying birds with his friend Scott. He also enjoyed woodworking, fly fishing, kayaking, camping, mountain climbing, and marathon running.

I think what kept Norman going at the BAM, even after his diagnosis with multiple myeloma in 2012 and the grueling battle that ensued, was his interest in young people. Norman had a kind of 1960s sensibility that the only really smart or principled people in the world were those who had not yet turned 30. Brown was just the right place for him. When he talked about his nephew Alex’s musical exploits, the interns who passed through the BAM, the children of BAM staff, or the dozens of Brown students he interviewed, Norman’s softer side came alive. And no one could light him up more than his daughter Nicole, the real center of his life.

Norman wasn’t always the easiest boss, but he could exhibit heartbreaking tenderness. Early on in my time at the BAM, I was stuck in Providence for Thanksgiving. Norman invited me to the family gathering at his house in Sharon, where he and his wife Kathryn had recently moved from Coolidge Corner in Brookline. When I arrived we went for a short walk in the woods and all of his edginess seemed to melt away in the company of trees and birds. He was positively gleeful at discovering an owl pellet. When we got back to his house, his family had arrived and I got to see firsthand his reverence for his father and experience the crackling, good-humored tension between him and Kathryn over her use of paper towels, which he described as “profligate.” Later, when Kathryn won the New Yorker’s “caption of the week” contest, I honestly think it was one of Norman’s proudest moments.

When I found out that Norman had passed away, my thoughts turned to that Thanksgiving, and to a feeling that his memory will always evoke in me: a sense of the search, a desire for the great redemptive moment of meaning expressed in perfectly weighted words. Like his favorite writer Graham Greene, Norman had a deeply Catholic imagination and view of the world, one in which we are always struggling for redemption—especially when we fumble and fall and make mistakes. The search is always on for a better way to turn the phrase or tell the story. Always. This was his gift to me and to everyone who knew him.

Norman Louis Boucher died on September 11, 2020. He is survived by his wife Kathryn Sky-Peck, his daughter Nicole Gabrielle Boucher, his sister Florence Minasian and brother-in-law Richard Minasian, his sister Louise Vaysi, niece Jasmine Vaysi, and nephew Alex Minasian. Norman took part in three clinical trials to advance knowledge and treatments for multiple myeloma; donations in his honor may be made to the Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation.