Lit.

How nicotine, alcohol, amphetamines, opium, cocaine, and even caffeine have fueled the world’s wars

“World War I was the best thing that ever happened to the cigarette,” writes political science professor Peter Andreas in his book Killer High: A History of War in Six Drugs.

A decade into the 20th century, hardly anyone smoked cigarettes and it seemed likely to stay that way. By 1914, as knowledge about the dangers of tobacco emerged, eight states had actually banned the sale of cigarettes and 20 others were debating passing their own anti-cigarette laws.

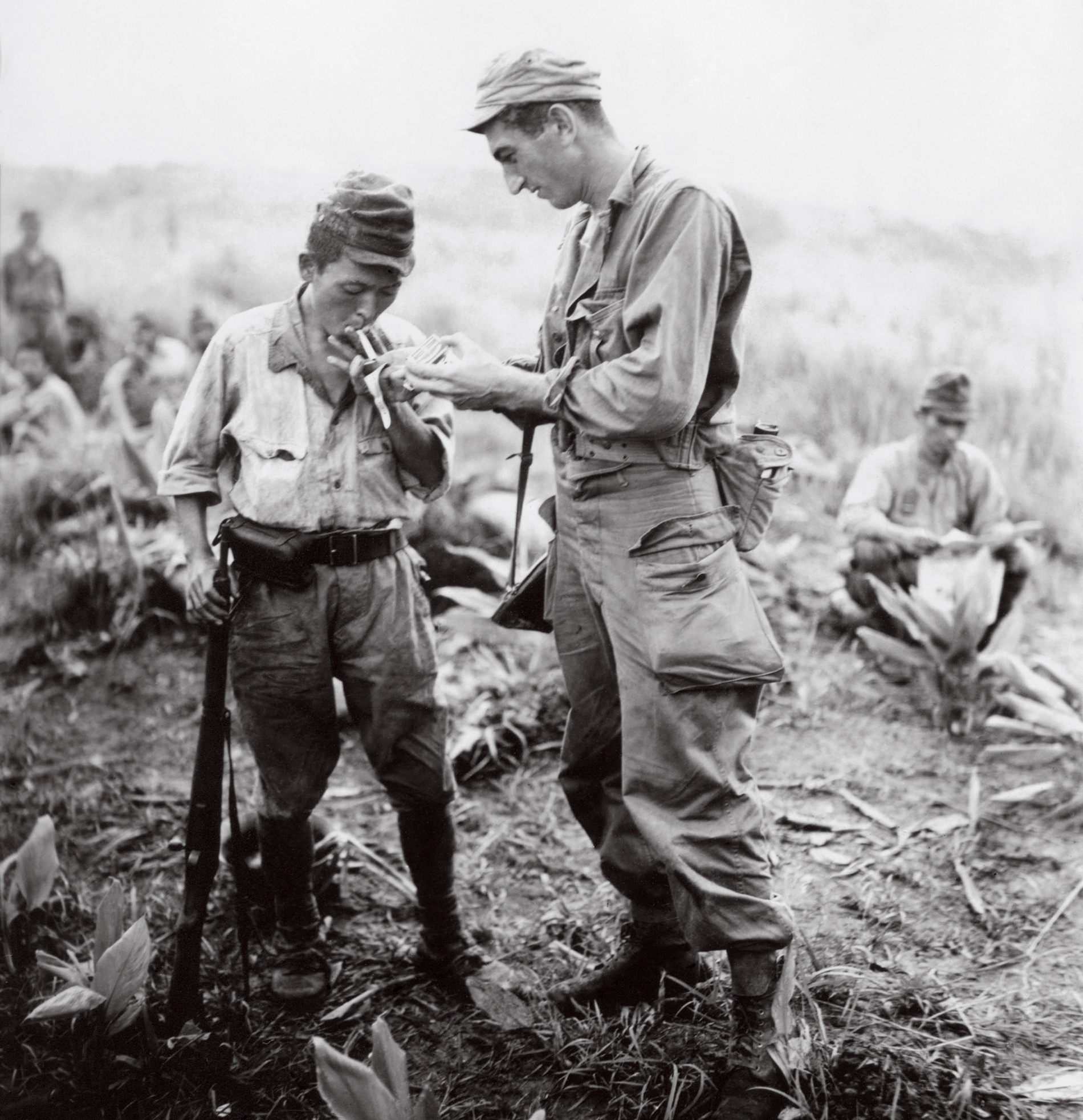

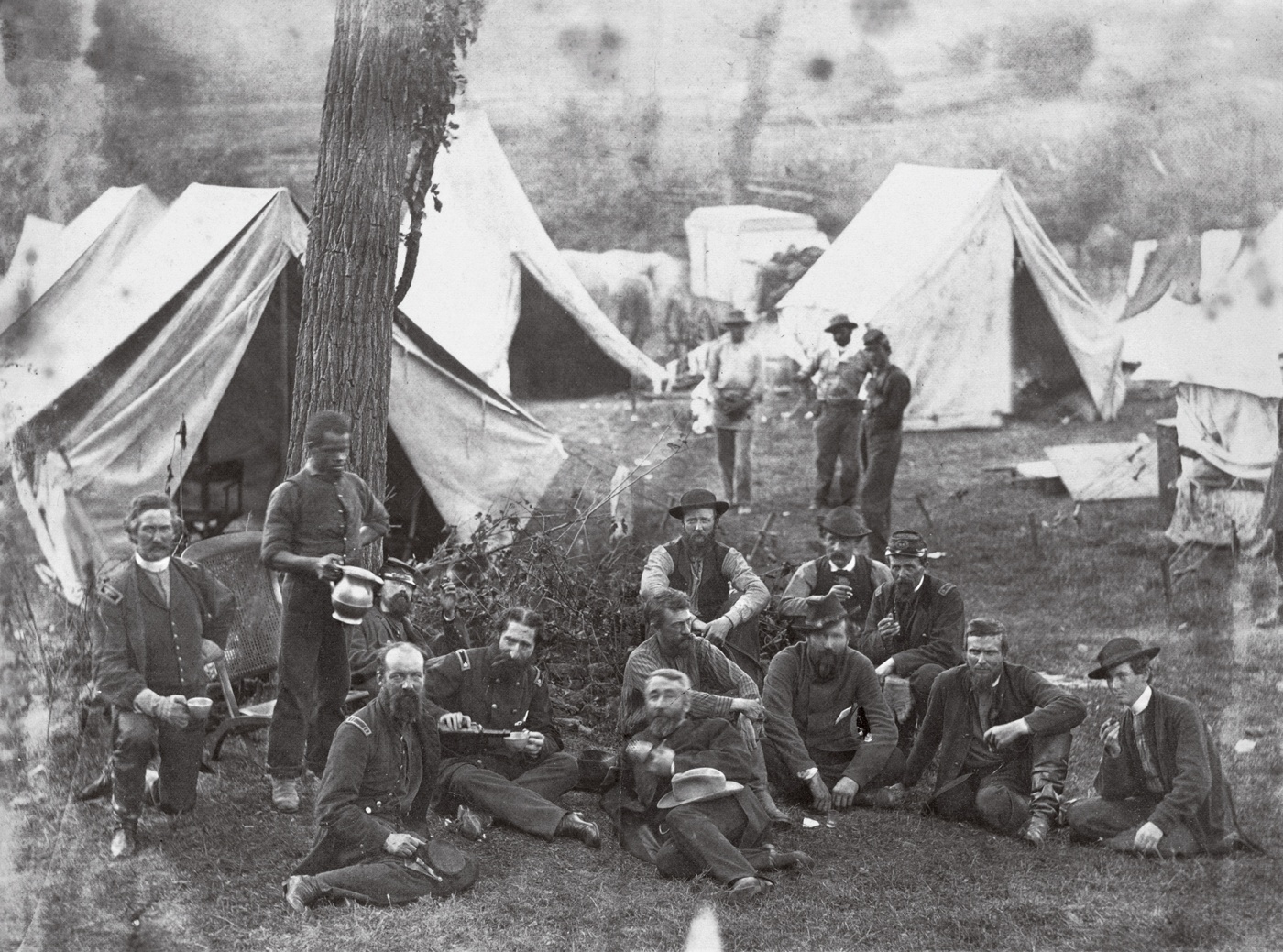

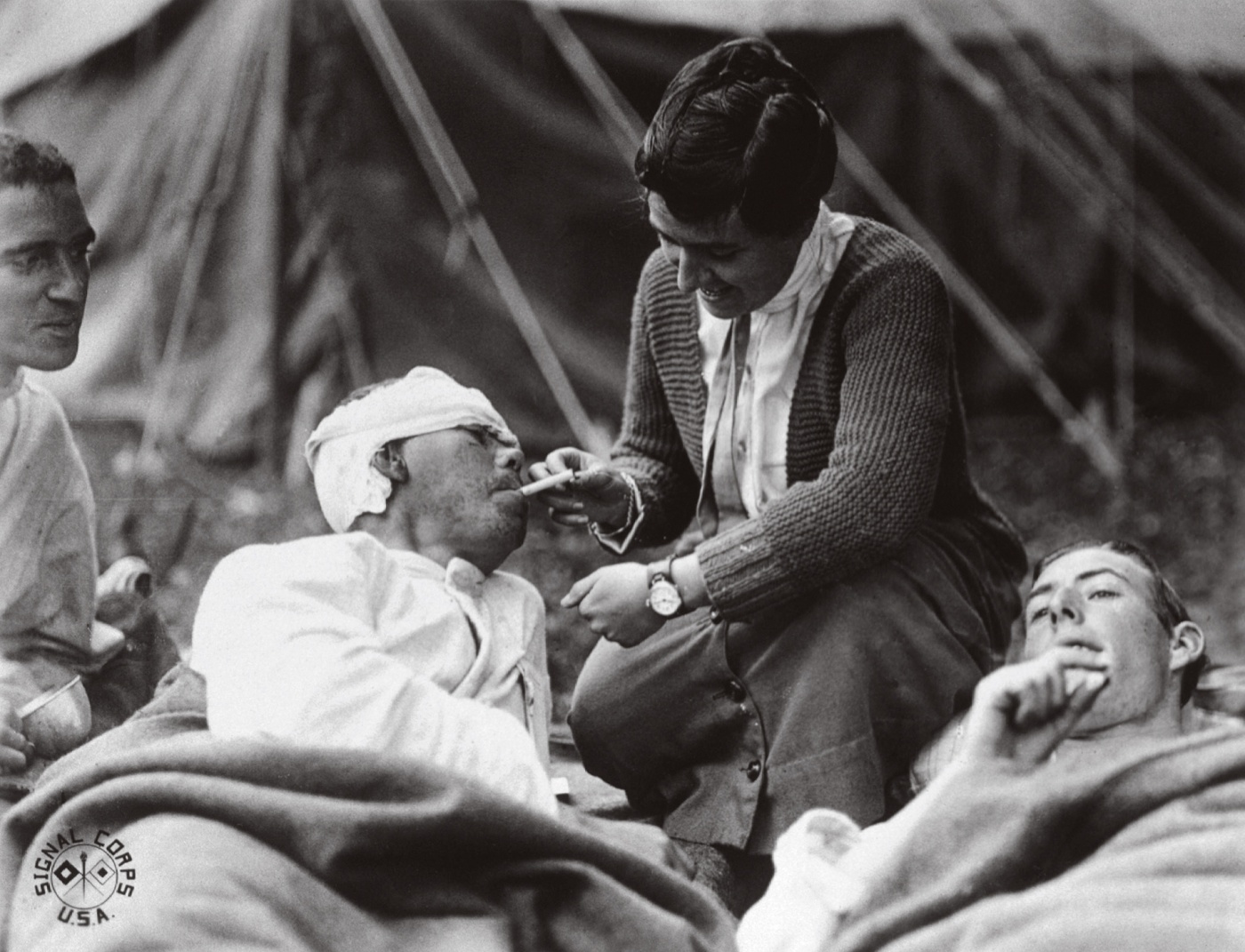

But after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria—the incident historians cite as being the match that lit World War I—the cigarette industry got a light, too, in the form of one of history’s biggest PR makeovers. By the time the U.S. entered the war several years later, smoking cigarettes was actively encouraged in troops. The Army’s chief medical officer started recommending cigarettes as essential for “contentment and morale” despite health hazards. It wasn’t simply the effect of the nicotine or the ease of transport that made cigarettes so popular—they also promoted camaraderie between soldiers and helped them pass the long hours of duty.

The U.S. government quickly turned into the tobacco industry’s favorite customer and cigarettes were soon a staple of the soldiers’ ration. Even the YMCA, which had been leading a high-profile anti-smoking campaign, reversed course and became one of the world’s foremost distributors of cigarettes, donating more than two billion to soldiers. At the war’s conclusion, cigarette production had tripled, millions of returning soldiers brought back their addictive habit, and tobacco companies had embraced a new, patriotic image.

The rise of the cigarette industry and the role of tobacco in war is just one chapter in Andreas’s Killer High, which examines “how drugs made war and war made drugs.” He focuses on five other substances: alcohol, opium, amphetamines, cocaine, and caffeine. Cannabis, however, doesn’t make the cut.

Cannabis and chill

“I was surprised that I ended up not writing about cannabis,” Andreas says. “I assumed that the world’s most popular illicit drug must be included in a sweeping history of the relationship between drugs and war.”

Andreas judged drugs based on their relationship to war in several ways—war while on drugs, war through drugs, war for drugs, and wars against drugs—and eventually concluded that cannabis hadn’t played the same outsized role in military history that the other drugs have (perhaps the world really would be more peaceful if everyone smoked some Mary Jane?).

“It is the perfectly licit drugs like alcohol and tobacco that have been the most exploited for war-making historically,” Andreas explains. “These are war drugs that go back not just decades but centuries.”

Killer Caffeine

Take caffeine, a seemingly tame substance better known for fueling bleary-eyed nine-to-fivers than militaries and war. Then again, remember the Boston Tea Party? (Those colonists weren’t drinking decaf.) Or consider the rise of Coca-Cola, which cemented its global empire during World War II after it set up dozens of bottling facilities on American military bases across the world (often paid for with taxpayer dollars) to keep troops happy and hydrated with its caffeinated drinks.

Drug money

As habit-forming products extremely profitable relative to their size and weight, the mass appeal of drugs built and sustained empires and played often overlooked roles in influencing military affairs. In Russia, tsars relied on revenue from vodka taxes to build up Europe’s largest standing army, only to end up with overly inebriated and thus ineffective soldiers. When a frustrated Tsar Nicholas II banned vodka in 1914, Russia’s military performed (even more) poorly in World War I, a fiasco that helped spur the Bolshevik revolution.

Soldiers’ little helper

Germany’s blitzkrieg invasion of Europe to spark World War II was infamously energized by amphetamines, as the Nazis became notorious for popping pills to keep marching for days on end without sleep. The United States military also embraced speed during the war, ordering Benzedrine to supply its 12 million overseas servicemen with “bennies” to stay sharp while on duty. At the time, no one seemed to worry much about the health consequences given the stakes of the war. Even today, the U.S. Air Force offers amphetamines to pilots.

In this vein, while Killer High’s cocaine chapter deals with the more contemporary “war on drugs” efforts by the U.S. to stem trafficking in countries like Mexico and Colombia, Andreas is more interested in exploring how countries like the U.S. and Britain have exploited both legal and illegal drugs for their own military gain.

State-building substances

“What’s astonishing is just how important drugs have been in building up states—and not just any states but the great powers of the world,” Andreas told BAM. “Their very origins have been intimately intertwined with exploiting drugs for war-making purposes.”

When it came to producing and distributing narcotics, the notorious El Chapo had nothing on the British East India Company, “the largest drug-trafficking organization in the history of the world,” according to Andreas. For decades, the company had illegally imported vast amounts of opium into China—until Chinese officials finally cracked down in 1839, only for the company to respond with the full force of the British military to keep the drugs flowing in. The war and its aftermath allowed Britain to maintain a strong imperial grip on China.

Just say no

The Brits didn’t always come out on top, however. They arguably led the world’s first (and certainly one of the most famous) failed war-on-drugs campaign, trying to stop the smuggling of molasses from the French West Indies into 18th-century New England colonies where it was used to produce rum.

Though British customs agents had tolerated the smuggling for decades, following the conclusion of the costly Seven Years War with France in 1763 the Crown ordered the Royal Navy deployed to crack down on the smugglers. The military campaign against molasses—key to New England’s economy and spirits—spurred a violent backlash (including the infamous burning of the British customs schooner, the Gaspee, by Rhode Islanders in 1772).

“I know not why we should blush to confess that molasses was an essential ingredient in American independence,” John Adams would later write.

Drug country

For a nation whose origins stem in part from drug-running, there is a certain amount of irony in the contemporary rhetoric from American politicians who have spent the past few decades railing against shadowy drug cartels and illegal traffickers inside and outside the U.S.

Even at the height of its War on Drugs, the U.S. government continued to rely on drugs to help advance its military interests. George H.W. Bush may have held up a bag of cocaine and declared, in 1989, “All of us agree that the gravest domestic threat facing our nation today is drugs,” but his administration was also allegedly supporting Contra rebels in Nicaragua with the sale of cocaine via CIA-contracted air transport companies.

Following the rise of cocaine as a glamour drug in the ’70s and ’80s, Andreas chronicles how “fighting a white powdery substance turned into a military crusade.” With leaders like Bush condemning drugs as a national security threat, Washington enabled “the militarization of policing and the domestication of soldiering.” Cops increasingly employed counterinsurgency tactics from Vietnam in American cities and funding of law enforcement swelled. Even so, Andreas points out that Washington’s focus on stopping cocaine from pouring into South Florida through the Caribbean in the ’80s inadvertently helped lead to the rise of the U.S.-Mexican border as the main drug portal into the United States. Colombian cartels, searching for a new entry point into the U.S., became increasingly reliant on Mexican drug traffickers to help push their product.

Arms race

Meanwhile, Mexico, pressured by the U.S., has taken to trying to solve its drug-trafficking problem with military power. Applying military force to suppressing drugs hasn’t stemmed drug-

related violence, Andreas argues, but has actually made things worse and blurred the lines between battlefields and neighborhoods.

“With soldiers turned into cops and criminals as heavily armed as soldiers,” he writes, “the distinction between military conflict and criminal conflict has become increasingly fuzzy.”

Many cartel members are ex-soldiers, he adds, and one particularly violent cartel, Los Zetas, was founded by former members of an elite U.S.-trained anti-drug unit.

While not the main focus of his writing, Andreas suggests there are a range of alternatives available to Mexico and the U.S. to deal with drug trafficking and the violence that seems to come with it. Investing in strengthening and improving criminal justice institutions could help, he believes, as would the ultimate act of disarmament: decriminalizing drugs (or, at least, some of them). Prohibiting drugs, of course, allows criminals to profit from them and justifies governments investing more money into military responses to drug-trafficking without actually solving the underlying problem. (Take out one drug trafficker and another one soon moves in to fill the void.)

“A world without war unfortunately seems about as realistic as a drug-free world,” Andreas concludes. “One thing that we can therefore predict with some confidence is that drugs and war will continue their deadly embrace, making and remaking each other in the years and decades ahead.”

Nevertheless, Andreas does have another observation: Where there are wars there are drugs. But not necessarily the other way around. That, he says, is a choice.

Jack Brook ’19 is a 2020-2021 Luce Scholar and received the 2019 Betsy Amanda Lehman ’77 Award for Excellence in Journalism.