Ghost Dose

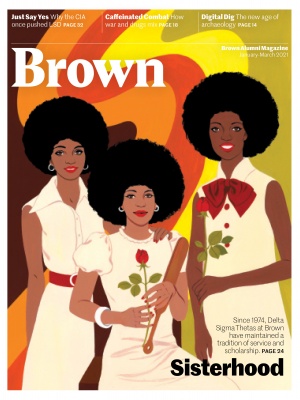

The true story of the CIA’s secret experiment with LSD in the search to create a Manchurian Candidate

The year is 1955.

A “national security whorehouse” referred to as “the pad” is surreptitiously moved from a hole-in-the-wall in New York City to Telegraph Hill, San Francisco—to 225 Chestnut Street, to be exact. There are heavy red curtains in the bedrooms, sex toys in the drawers, and what one CIA agent would later call “the most pornographic library I ever saw.”

The CIA wasn’t there to bust underground prostitution—far from it. In fact, the agency operated the brothel, paying a dozen prostitutes to drug unsuspecting johns with LSD and record their reactions. It’s an incredible chapter in U.S. intelligence history that’s recounted in Poisoner in Chief: Sidney Gottlieb and the CIA Search for Mind Control by Stephen Kinzer, who is currently a senior fellow at Brown’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs.

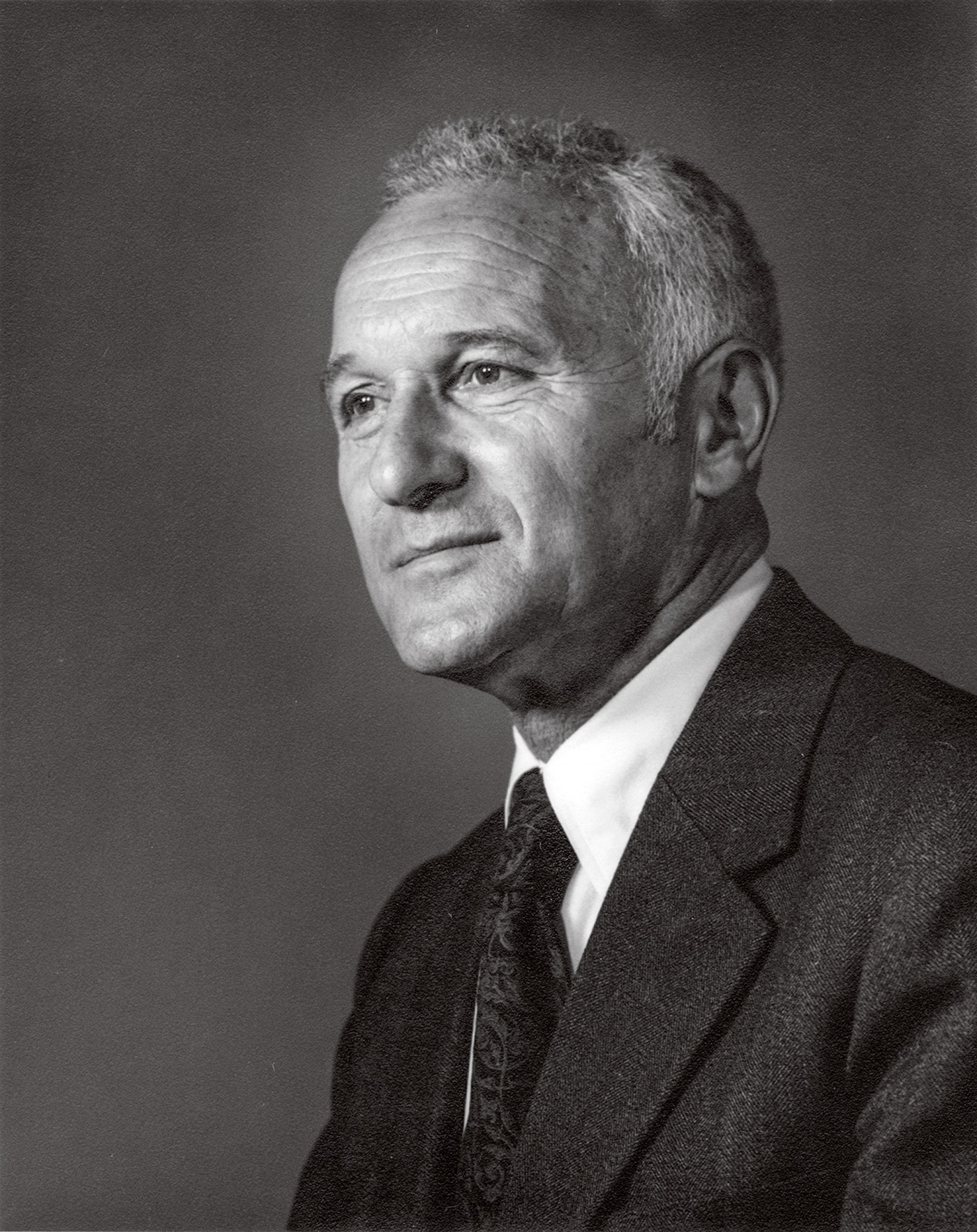

A foreign correspondent for the New York Times for more than 20 years and the author of books investigating U.S. interference in international affairs from Guatemala to Iran, Kinzer is no stranger to the strange-but-true—nor to the dark underbelly of our federal government. However, with the research and publication of his tenth book, published in late 2019, there came surprises that even he wasn’t ready for.

“In [writing] my books I’ve discovered many surprising things, some of which have shocked some people,” says Kinzer. “But this is the first time that I can’t believe that this happened, and that a person named Sidney Gottlieb did the things that he did.”

Would-be assassin

The inspiration for Poisoner in Chief came from one of Kinzer’s previous books, The Brothers: John Foster Dulles, Allen Dulles, and Their Secret World War. Kinzer had researched a brief anecdote about President Eisenhower’s assassination order on Patrice Lumumba, then prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and learned that an unnamed CIA agent had smuggled poison into the Congo with the intent of sneaking it onto Lumumba’s dining table. Although ultimately not selected as the preferred assassination style of the U.S. government, the poison was exquisite in its stealth and genius—if consumed, it would replicate the effects of a disease indigenous to the region.

Long after finishing Brothers, says Kinzer, “that story stuck with me. I began to wonder, who was that CIA officer?” Further research revealed the would-be assassin was not a standard CIA operative but the head of the chemical division for the CIA’s technical service staff. He had not only delivered the poison, but also manufactured it—along with every iteration of the dozen poisons intended to kill Fidel Castro. And for this man, concocting poisons to take down foreign leaders was merely a side hustle. For this man was Sidney Gottlieb, the mastermind behind MK-Ultra, a CIA program that set out to learn the secrets of mind control.

Poisoner is a biography that uses the timeline of the little-known Gottlieb’s life to stitch the birth, blossoming, and downfall of the CIA’s most outlandish project into the fabric of American culture. Sci-fi fever dream meets reality in some of Kinzer’s descriptions of MK-Ultra experiments, many of which have had lasting implications on civilian life today. The San Francisco brothel operation—Subproject 42, colloquially known as Operation Midnight Climax among agents—was just one element of a wide-ranging and often deeply troubling plan to explore psychedelic drugs that inadvertently helped popularize them in mainstream counterculture. In one early experiment in Germany, prisoners of war were drugged, interrogated, and then allowed to die. In another, ex-Nazi scientists were invited to partner with central intelligence to better study how to break the human will.

And at the center of MK-Ultra lay Gottlieb, a cipher. “It was difficult to write because in a sense, Gottlieb was invisible. He lived in complete anonymity—nobody knew his name or what he did,” Kinzer says. “I thought that through him I could tell a great story, but it’s the biography of a person who was not there. How do you reconstruct that? How do you penetrate the heart of this man’s mystery?”

The answer? Nine months of intense study, field trips from German death camps to Bronx apartments, and a willingness to think outside the box. For Kinzer, that meant experimenting with a new research tactic: inviting Brown students to help write the book.

Student sleuths

“This was the first time I’d ever asked students to participate in my research, but I realized early on how multifaceted this project was going to be,” says Kinzer, who cites 14 Brown students and one student from Emory University in the book’s acknowledgements. Although the use of student research assistants was a sharp deviation from his usual research methods, it proved fruitful.

“Student research produced some very interesting insights, including several that I might not ever have found on my own,” he says, pointing to one student whose family happened to know one of the officers who knew Gottlieb during his time at the CIA, and another who dug deep into Gottlieb’s childhood records to find his college letters of recommendation. One pair of research assistants, Isabel Paolini ’19 and Drashti Brahmbhatt ’19, spent months combing through fragments from heavily redacted documents released in 2004 and 2018 that described 140 of the MK-Ultra subprojects, trying to piece together a timeline for some of the initiative’s experiments.

“It was daunting at first to start researching all these various subprojects because the information was released in a way that discouraged people from even looking at it. You don’t really know when you’re looking online which sources are real, which are fake, and which are telling the truth,” Brahmbhatt says. “You just kind of have to plunge into the dark web, see which link leads to which link, and triangulate a bunch of sources.”

Even with over a dozen extra hands on deck, Kinzer says certain stones had to be left unturned. The CIA destroyed, classified, or “disappeared” much of the evidence of Gottlieb’s work, and whether or not the world will ever have access to that information remains as much of a mystery as Gottlieb himself. The book puts it succinctly: “Everything in this book is true. But not everything that’s true is in this book.”

“It was a frustrating process,” Kinzer says. “I’m painfully aware that I’ve only discovered a portion of what MK-Ultra was and what Sidney Gottlieb did, but I’m happy to have contributed something that clarifies and brings to public attention this astonishing and bizarre project.”

The Manchurian within

International Relations Professor Rose McDermott, a colleague of Kinzer’s at Watson, points out how eerily relevant Gottlieb’s search for mind control as a political weapon is to today. As a former student of controversial Stanford professor Philip Zimbardo and former classmate of a Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh cult member, McDermott knew there was a dark history of experiments that harness psychology as a tool for power or otherwise warp the boundaries of ethical research. Scientists, she says, can become blinded by fervor for their own experiments.

“For all the effort that was put into trying to create some kind of strategy or drug that would allow the U.S. government to reliably create a Manchurian candidate, nothing worked,” McDermott says. “The thing that’s fascinating to me is that the only people it really worked on were the people in the MK-Ultra program itself. Gottlieb and his whole crew managed to seduce themselves ... about the ability of this program to work.”

McDermott argues that self-brainwashing tactics—and their consequences on society—continue to permeate political institutions today.

“I think it’s a huge issue in our political system,” she says. “People change their minds, change their opinions, and partly how they do that is they do it to themselves.” While McDermott notes that this might seem like an obvious statement, she adds that the real insight from Gottlieb’s work is that, while people can’t necessarily shift other people’s perspectives using strange potions or brute force, the “soft power” influence of various groups, or even individuals, can make people want to change their own minds. “You do it to yourself based on the information you expose yourself to, the communities you participate in, the kinds of news outlets that you seek out, and the ones you choose to trust.”

Whether it’s politicians rushing to the extremes within their parties or the masses of loyal supporters they bring with them, McDermott points out that modern phenomena like deep political polarization or sharp partisan rifts over social issues aren’t so far off from the mentality that enabled Gottlieb’s team to torture in the name of the greater good. At some point, it becomes less about the evidence and more about a desperate desire for the ideas you believe in to come true.

‘Emergency’ inflation

For Kinzer, Gottlieb’s ability to keep up his mad-scientist antics for more than a decade without raising eyebrows within the CIA illustrates another phenomenon he considers alive and well today: state-of-emergency mentality.

“The CIA justified Gottlieb’s decisions by saying that we were in such an emergency situation that we could no longer observe the traditional rules that we would normally obey. During that period of the Cold War, people were told that it was such an emergency that we had to do things that were distasteful, but that times demanded them,” explains Kinzer. “Today we’re in a similar situation. We’re told that because of the threat of terrorism from enemies to the United States, regrettably, we must bend some of our commitments to civil liberties, ethics, and morality. We’re told that we will go back to those principles that shaped America once the emergency is over. But the emergency never seems to end.”

MK-Ultra eventually spiraled out of control, marked most notably by Gottlieb drugging a colleague to observe the effects; the victim jumped—or was pushed—out a window. Ended by 1965, it nevertheless influenced CIA prisoner strategies for generations. The most notable recreation of MK-Ultra tactics occurred with the Phoenix Program, in which Viet Cong members were identified, tortured, and murdered during the Vietnam War. However, many of the questionable interrogation procedures still employed by the U.S. government are directly borrowed from Gottlieb’s methodology. “Drugs, sensory deprivation, various forms of torment—Gottlieb’s manual about how to break prisoners’ resistance and make them cut ties to the outside world and transfer those ties to the interrogator became the basis for future CIA interrogation projects,” says Kinzer.

He views Gottlieb’s story as a warning. “He was part of a national hysteria. I’d like to imagine that people who are carrying out horrific interrogations and other forms of torture on behalf of the U.S. government might look back on the Gottlieb story and realize that not only does this not produce good results, but it paralyzes the moral sense that is supposed to animate a democratic republic.”

Secrets of Keeney Quad

One of the most shocking discoveries for student Isabel Paolini ’19 was learning of Brown University’s involvement with the project. “The president of Brown University in the fifties and sixties worked for the CIA,” explains Paolini of Barnaby Keeney, former history professor and the University’s 12th president. Keeney’s legacy today is a freshman dormitory whose well-lit and brightly painted walls offer not even the slightest hint of his involvement with the agency, including his brief departure from Brown in 1951 to work there full-time. In 1962, while still at Brown, Keeney also became the chair of the Human Ecology Fund, the major organization through which money from the CIA flowed into many of the MK-Ultra projects.

“Jason Bourne and a lot of these spy movies I see, I’m now like, ‘These aren’t as far-fetched as they first appeared,’” reflects Paolini. “A lot of universities were both wittingly and unwittingly associated with many of the subprojects, but Brown’s particularly acute participation was startling. It really brings into focus the need for better observation and control over what bureaucracies are doing inside their own walls.”

Kinzer is hopeful that Poisoner in Chief will do just that. “This story is not just a story about the past. I think as people close the book, it will be logical for them to reflect on the present,” he says. “Technology is much further advanced than it was in Gottlieb’s time; the size and scope of the security state is unimaginably greater than back then. It would be naïve to think that if some crazy project like MK-Ultra could happen in the 1950s, it couldn’t happen today. In fact, the opposite is probably true.”

Ivy Scott ’21 studies international journalism and French. Her writing has appeared in the Providence Journal and the Boston Globe.