Everything Old Is New Again

Technology and new questions bring long-studied archaeological sites to life.

Inside Bronze

Engineering Professor Brian Sheldon never figured he’d get into archaeology. But in the late 2000s, researchers from the Joukowsky Institute for Archaeology and the Ancient World approached the materials scientist for help analyzing some of their finds. So the engineering professor turned his attention from the thin films used in lithium-ion batteries, sensors, and fuel cells to what were, for him, entirely new research questions. “They wanted to better understand people’s cultural heritage,” he says. “That’s not exactly my area.”

Through connections at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Sheldon was able to introduce his new colleagues to neutron imaging—a process that passes neutrons through an object, collects them in a receptor, and then renders images of the internal structure and composition of the sample. Sheldon and the team sent some Roman coins, an oil lamp, and a small figurine of a dog to Oak Ridge and made a range of discoveries about the objects’ materials and how they were fabricated. More importantly, he says, they learned how much more there is to learn from ancient materials using these techniques.

Unfortunately, Sheldon says, continuing this line of inquiry is a daunting challenge. “In the U.S., the archaeological science community is really tiny. In the U.K. and Europe there is much more support to do the work,” he notes. “I have an easier time getting money to do my regular research program than to do this. I wish I could do more of it.”

The Post-Colonial List

Sometime around 1860 BCE, Egyptian pharaoh Senwosret III built a string of fortresses along the upper reaches of the Nile River. They remained in use for more than 150 years, but only two exist today, and one of them, Uronarti, sits in the upper reaches of a reservoir created by the Aswan High Dam. Just inside the northern border of Sudan, Uronarti is surrounded on all sides by thousands of square miles of empty desert. It’s many miles from a reliable source of electricity.

Laurel Bestock ’99 started doing archaeological fieldwork in Uronarti when she was an undergraduate. “The location is not easy,” she notes. “When we first got there, we discovered we couldn’t camp in the fortress. It was just too much work to supply ourselves with water.”

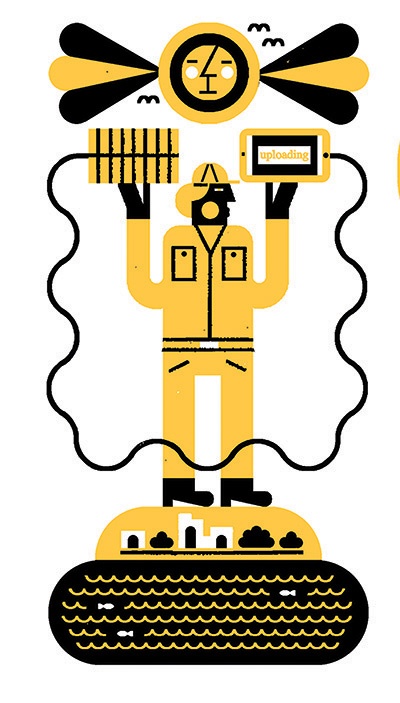

New technologies have proliferated in archaeological fieldwork, but most require internet access, and all need electricity. Bestock and her partner solved the electricity problem with solar panels and designed customized software for iPads to help mitigate the constrained connectivity. “We wanted this to be useful for teams that don’t have a tech guy or a big budget,” she says—“and that’s most of them.”

Fieldwork and data collection are on hold due to the pandemic, but there is some good news: “There is real movement toward normalizing relations with Sudan. That would make my project much easier to run.” And changes to how ancient sites are studied today go well beyond the tools of fieldwork, Bestock says. When Uronarti was excavated in the early 20th century, for instance, archaeologists “were really trying to understand its history in the context of conquest—in the sense that colonialism was a good thing.” Our views of colonialism have changed somewhat since then, Bestock notes, which begs many new questions. “For example, I want to know what was happening in the communities outside and around the fort,” she says. “All of that is completely new.”

Monastery Magic

“We have been working on the same site since the 1980s,” says Professor Sheila Bonde of L’Abbaye Saint-Jean-des-

Vignes, a medieval monastery in northeast France. When she’s able to return post-pandemic, she’ll have new questions. “The site hasn’t changed,” she says, “but we have.”

Bonde and her monastic archaeology project codirector, retired Wesleyan Professor Clark Maines, know a lot of who, what, when, where, and why. But recently they returned with a 21st-century question: How did it feel? “We’re interested in using the sensory as an approach to expressing what we know,” she says. “What did people hear, see, feel, smell, and touch as part of the monastic experience?”

Their forthcoming scholarly digital project, The Sensory Monastery—“neither e-book nor website,” Bonde says—includes semi-fictionalized narratives of seven individuals and a range of other digital assets that Bonde hopes will help people “feel” what monastic life was like.

Founded in 1076, the abbey evolved continuously over its lifetime as a self- sustaining community, with gardens, stables, beehives, kitchens, water and sewerage systems—all details that were carefully coordinated around the monastic experience, says Bonde, a professor of both history of art and architecture and of archaeology and the ancient world.

Several characters in The Sensory Monastery are people who lived at Saint-Jean. One is a 13th-century abbot: another is a female benefactor who was buried in the chapter room. “We explore the ‘factual’ bases for their lives, but also the kinds of sensory stimuli they might have experienced.” The project is part of Brown’s Mellon digital initiative.

On a recent trip to France, Bonde and Maines spent time recording what she calls “analogues for medieval sounds.” A modern French church bell might not be the same as a medieval one, but it’s as close as she’s going to get. “I would give my eye teeth for five minutes on site back then,” says Bonde, who has written or coauthored two books and 30 articles about the Abbey. One challenge to these recordings is tuning out the modern world—airplanes, car horns, language—or finding quiet at all. “Silence was a really important part of monastic life,” she says. “Sound was a way they experienced the glory of the world God created, but observing silence helped them to hear the spiritual.”