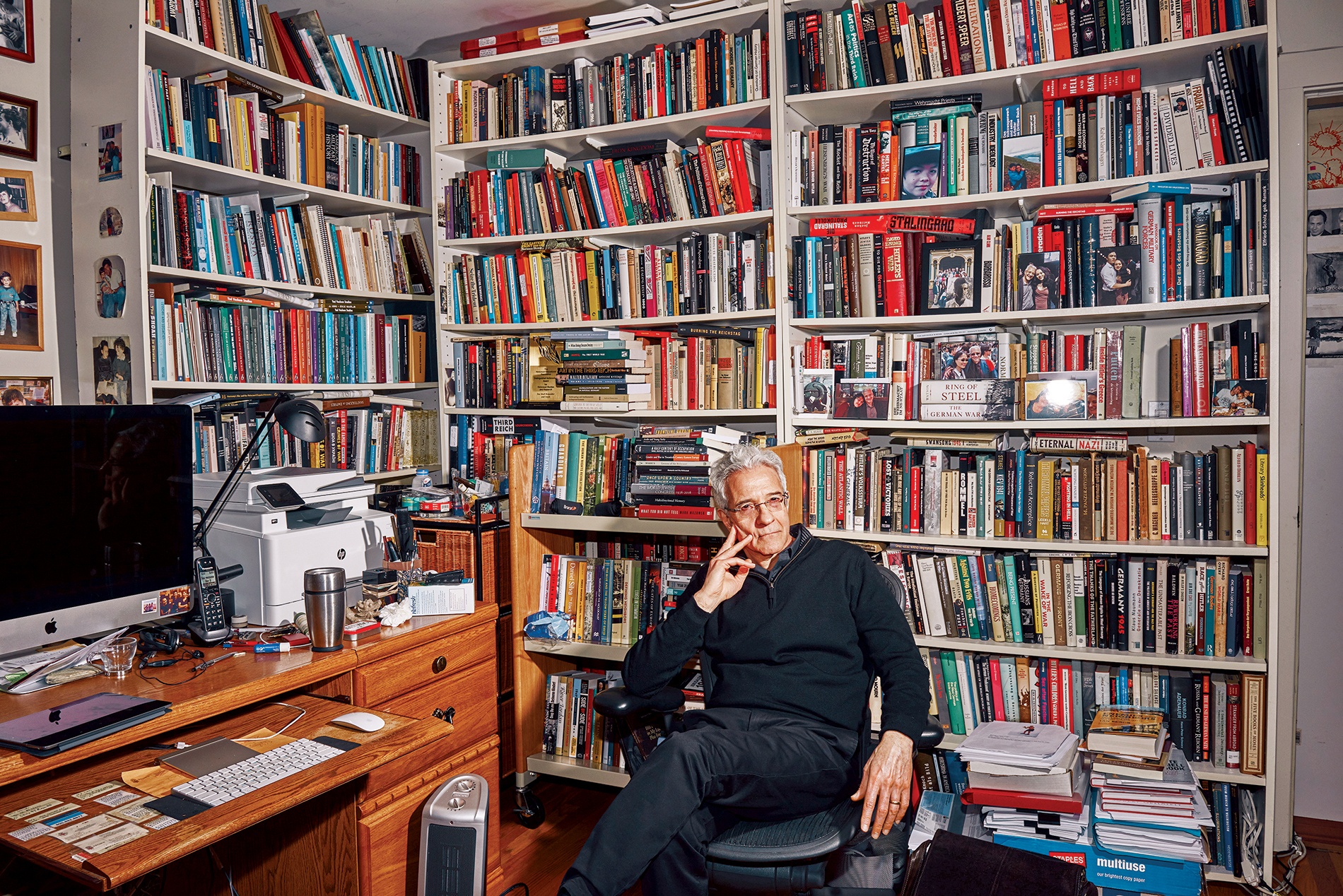

Eyewitness History

First-person accounts are often ignored in official histories of global crises. Holocaust scholar and history professor Omer Bartov explains why that’s a mistake.

First Person History in Times of Crisis: Witnessing, Memory, Fiction”—that’s the name of the graduate seminar that Omer Bartov, the John P. Birkelund Distinguished Professor of European History at Brown, is scheduled to teach in fall 2020. But first, in late February, Bartov relocated to Tel Aviv to offer a Hebrew University course on “two traumatic, violent experiences”—the Holocaust and the expulsion of Palestinians from the future state of Israel. Not even three weeks later, on March 19, after the University shuttered its campus, he found himself flying home to teach the three-month class online.

“My environment was closing in on me,” Bartov remembers of his short time in Tel Aviv. “I had a small apartment, a room and a bed, and you could increasingly not go out. I was afraid I would get stuck, so I just hopped on an airplane. It was not the most fun flight—I was cleaning surfaces, putting on a mask. People were nervous.”

One advantage to Bartov’s experience was the opportunity to observe divergent responses to the pandemic. “Israel,” he says, “is a very intimate society. People rub against each other all the time—physically, too, not just metaphorically. Tel Aviv has a lively nightlife and people meet in cafes all the time. It’s an energetic environment day and night. To see that wither was extraordinary. It was just totally disorienting.”

As of late March, with rising numbers of COVID-19 infections, social distancing measures in Israel had become even more severe than in most of the United States and were subject to police enforcement. “Americans naturally think that what is happening to them is what’s happening,” Bartov says. “One thing we will probably learn from this is how different societies and individuals in those societies respond differently to such terrifying events.”

Subjective storytelling

First-person accounts such as Bartov’s surely will become fodder for future historians—as well as for Bartov’s own graduate seminar, which has focused on the Holocaust and encompassed diaries, oral histories, court testimonies, memoirs, historical fiction, and film. The syllabus incorporates such topics as “false memory,” “realism and authenticity,” “fantasy and pleasure,” and “kitsch and death.” Fiction, Bartov notes, “creates its own artistic truth” and has a relationship to “historical ‘truth,’ which by definition is at best slippery and contingent.”

While times of crisis and conflict give rise to “often rigid narratives,” polarized between contending sides, personal accounts can foster complexity, nuance, and empathy. “They provide a multitude of perceptions,” he says, “that contradict each other in ways that break down the conventional narrative and collective memory of an event.”

A scholar of both the Holocaust and comparative genocide, Bartov has become an influential advocate for the integration of first-person perspectives into historical narratives. He translated theory into practice in his 2018 book, Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz, an intimate account of the Holocaust in his mother’s native town in present-day Ukraine (see “What Would You Do?” May/June 2018).

Official omissions

Early historians of the Holocaust, Bartov says, tended to rely primarily on official documents created by the perpetrators. “They were wary of using individual testimonies because they saw them as subjective and often inaccurate. Because they were writing about an event of extreme dimensions, they thought it was better to use the most objective kind of documentation.”

The result, he says, was the omission of important perspectives from victims, survivors, bystanders, and others. “What you see from below is not what you see from above,” he says, “what you see from afar is not what you see from nearby.”

Because of its thematic approach, Bartov’s class draws graduate students from diverse subfields in history, as well as from other disciplines. So in addition to the core readings, he asks each participant to supply a class reading list, make presentations, and write papers in an area of special interest. In the past, he says, students have explored such topics as lynching in the American South and the Spanish Inquisition.

Bartov says he hasn’t yet considered “in a structured way” how the pandemic might figure in the course. But since the crisis is still unfolding, he says, “we won’t have perspective yet—we’ll only have the real-time effect,” as chronicled via social media and in other forms of reportage.

Pandemic vs. plague

Comparing the current pandemic to past plagues, Bartov says they share “the common sense of helplessness against a deadly foe. Suddenly, the world is faced with something for which there’s no cure…. Ultimately, you’re just like somebody living in the fourteenth century.”

He also cites the collision—and possible elision—of scientific and magical thinking. Because of how much is still unknown about COVID-19, “scientific thinking itself is being challenged,” Bartov says. And while we naturally wish for a vaccine or cure, “the magical thinking is that they will come up with it right now, that they’ll have some medication tomorrow.”

Citing historical parallels, Bartov worries about political, social, and economic impacts. “This kind of epidemic quickly reveals all the fault lines in your society,” such as inadequacies in the medical system, economic inequality, and social tensions. “Everything that was sort of holding together as long as things were going well falls apart.”

While the United States withstood the Great Depression, in Spain, Italy, and Germany, massive unemployment, social disintegration, and the resulting hopelessness and resentment were “the main cause of the rise of fascism,” Bartov says. “You have to think that this [pandemic] may be the beginning of much greater social and political upheaval.”