Crazy Times, Sane Decisions

Bina Venkataraman ’02 on why it’s more important than ever to plan ahead—and how to do it.

You remember: As the U.S. began to take note of the novel coronavirus, nervous edginess exploded into panic. Toilet paper flew off supermarket shelves, the price of Purell on Amazon skyrocketed to $99.99, and I saw one man arrive at Whole Foods in a Hazmat suit and welding mask.

“They’re looking for some form of control,” explains Bina Venkataraman ’02, editorial page editor of the Boston Globe and a former director of global policy initiatives at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, who spoke with the BAM in late March. “People want to have agency over a problem that is bigger than them.”

Venkataraman, a former science and technology policy advisor to the Obama administration who now teaches in the program on science, technology, and society at MIT, is also the author of The Optimist’s Telescope: Thinking Ahead in a Reckless Age, named one of the best books of 2019 by NPR. It’s a collection of research-based advice on the importance of foresight and—importantly—what keeps people from exercising it.

This spring—as streets, schools, stores, and salons emptied, all but the most essential employees were laid off or instructed to work from home, and members of the National Guard were stopping cars at state borders—it seemed if ever there was a time for mass hysteria, this was it. Venkataraman insists it was the perfect moment to keep calm and think ahead. “This pandemic and the way it’s evolved is just a really poignant example of how intervening earlier in problems can save lives and the economy,” she says. “We were asking people to act now to prevent a hypothetical future.”

Venkataraman cites the research of Swiss economists Helga Fehr-Duda and Ernst Fehr, which concludes that people tend to be much more willing to make personal sacrifices for a clear and predictable outcome than they are for some vague concept of the greater good. “We’re in a culture in which we focus a lot on prediction of the future, and that ability to predict and forecast has been honed by our scientific tools,” she says. “But even when people have really good predictions, they don’t always act to prevent harm.” To do so, we must develop an instinct for responsible application of what we know: “It’s really important to distinguish foresight from forecasting. Good foresight means having judgment; it’s not just about information, it’s also about wisdom.”

So how do we strengthen our foresight muscles, even in the midst of insanity?

Step 1: See the future

Not just any future. A happy one, in which your problems are resolved—and you’ve played a direct role in their resolution. Seeing yourself as the producer of positive outcomes is crucial to achieving them.

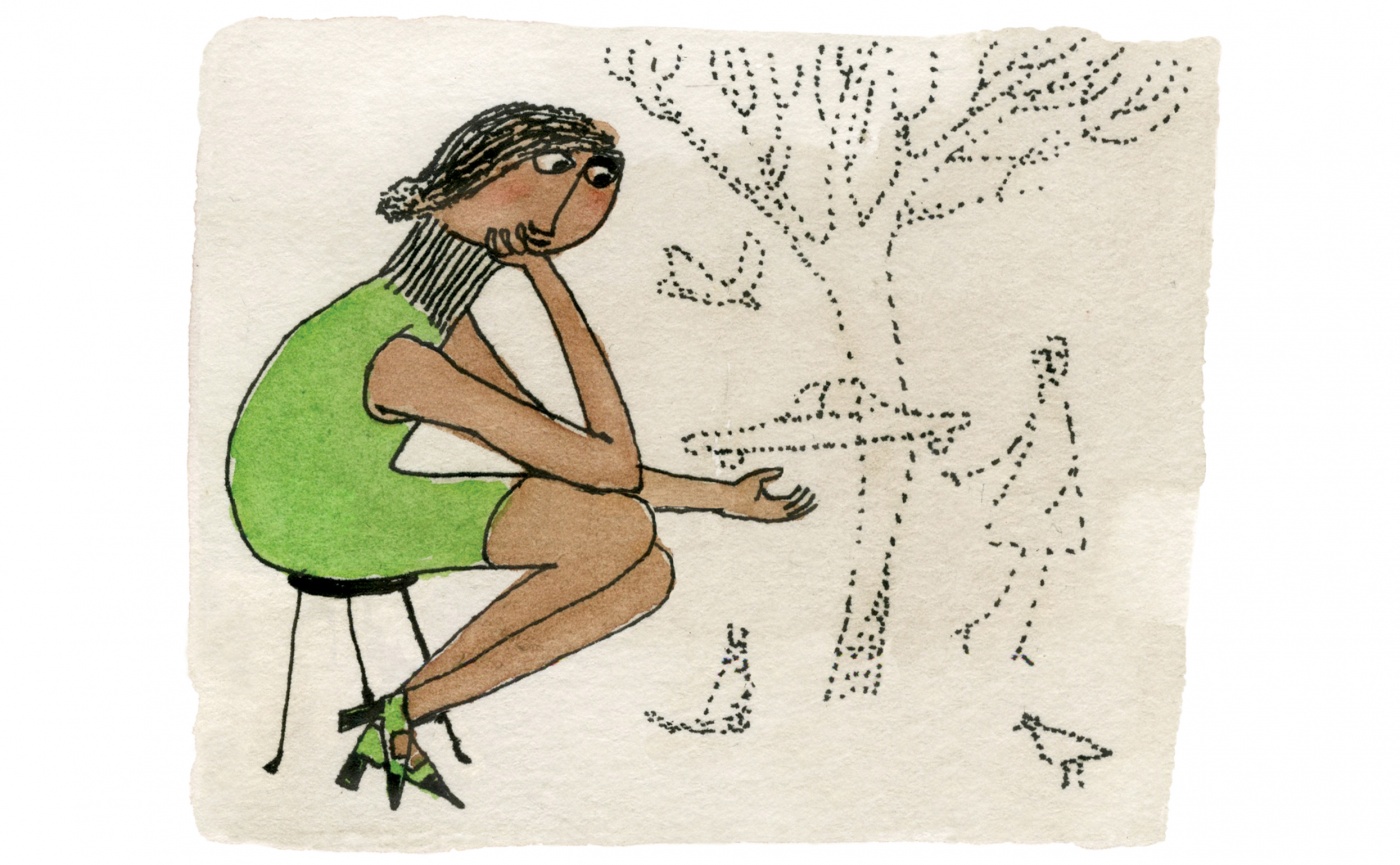

“When you’re facing such uncertain circumstances for the future, it helps to be able to lock on to a scenario of the future where things get better for you and for your family,” Venkataraman explains, a strategy she learned from the research of Wellesley psychology professor Tracy Gleason. “There will be a time when we can move about more or when this will get better. So focus on that scenario, and then on decisions that contribute to it. They might include taking better care to be virtually connected to elderly people, or saving money. Do things within your agency.”

The benefits to this literal interpretation of “forward thinking” are myriad. One section of The Optimist’s Telescope explores technology that helps young people get a better sense of old age. Economist and UCLA professor Hal Hershfield collaborated with a virtual reality designer to create avatars of his students as elderly people. Looking into the “magic mirror,” the student’s every movement would be mimicked by a version of what they might look like in 60 years. Hershfield reported these students were more willing to save money for retirement than those who simply looked at photographs of older people or read about the importance of saving.

A lower tech alternative: letter writing.

“I use this tool that I write about in the book—writing a letter to my future self to be opened in 30 or 40 years—to try to imagine what I would be like then, what would be important to me, and how I’ll explain my decisions today to that future person,” Venkataraman says, adapting the advice of Seattle-based entrepreneur Michael Hebb, whose book Let’s Talk About Death (Over Dinner) encourages people to arrive at their birthday dinner in a coffin. “It’s allowed me to make some pretty big decisions in my life, including deciding not to have a kid,” she adds. “I was able to get past the different fears I had making that decision, based on understanding that when I’m older I’m going to want to have kids around me, but that just means I want to invest more in my nieces and nephews.”

Carving out time each day to meditate on positive versions of the future, she says, is another way to imagine your life months or years down the road, and to take the first steps toward it.

As much as the book is a guide on what to do, however, Venkataraman also offers clear advice on what not to do.

Step 2: Check your metrics

Although high-tech inventions can encourage foresight, most are detrimental to good long-term decision making. “Social media platforms, even just getting a text message and having it ding as if it’s a reward,” she says—these technologies “give you a little bitty dopamine rush and focus your attention on something incremental.” Brain scientist Peter Whybrow labels them “electronic cocaine.”

“The number of likes you get on a post, the number of steps you took today, profits you earned in a quarter—these kinds of metrics can be very unreliable predictors of whether you’re going to be successful in the long run or will achieve real progress in the things you care about most,” Venkataraman cautions. “It’s important to think about what we measure.”

During a period when so many are working from home, the impulse can become even stronger to derive validation from social media or other digital platforms. To counter this, Venkataraman suggests a trick pulled from Chicago hedge fund investor Anne Dias and backed by research from University of California economists Brad Barber and Terrance Odean—and moms everywhere. Shut devices down for specific periods during the day or week. One example: take off the Fitbit on Saturdays and go for a run in which your surroundings and thoughts are what matter—not the number of steps.

“One of the insights that has helped me is carving out even just a couple hours a week where I don’t look at my email or measure myself by how many messages I’ve responded to, so I can think about my long-term goals,” Venkataraman says, a nod to entrepreneur William Powers’s tradition of a weekly “Internet Sabbath.”

Placing too much emphasis on incremental measurements, Venkataraman warns, can make even highly intelligent people ignore research and sound reasoning in favor of short-term gains. She shares the example that led her to start writing The Optimist’s Telescope, a series of encounters during her time as senior adviser on climate change for President Obama. “I was working in the White House and beating my head against the wall sharing the science of coming droughts and wildfires with business leaders and mayors, and finding that they would believe the science and take it seriously but not act on these problems of the future,” she recalls. “You’d have a business leader saying, ‘Well, that’s nice, but my shareholders and my board hold me accountable for what I do in the quarter, not what I do over the course of ten years.’”

Particularly in the context of something like a pandemic, she says, action from business and government actors isn’t just ideal; it’s necessary. “We’ve had a failure of leadership on this particular crisis at the national level and there has to be accountability,” she says. “We need to activate foresight on the part of our political leaders.”

Step 3: Find that heirloom

An heirloom is something—or someone—your community decides to shepherd and protect. Will it be a network of parks? Your grandma’s friends at the senior center? Venkataraman’s personal heirloom is an instrument that once belonged to her great-grandfather. “It’s called a dilruba; it’s a stringed instrument played with a bow,” she explains. “It was custom-made for my great-grandfather. He was a music and art critic in India in the early 20th century and he gave it to my grandmother, who gave it to me.”

Venkataraman was in her mid-thirties. “I suddenly started thinking of myself not just as a descendant of the person who had this instrument, but as an ancestor who needed to shepherd this heirloom through time,” she says. “I find myself treating it like no other object. It’s the most sacred thing I own because it’s connected to a past that is bigger than me. And it’s connected to a future, one bigger than mine.”

The same principle can, she argues, be applied on a larger scale. Based on Georgetown law professor Edith Brown Weiss’s idea of intergenerational equity, the idea has been adopted by academics and advocates across the social science fields. “In addition to laws and resources, we need to make meaning for people—a culture that uses the heirloom and interacts with it,” Venkataraman says. “So the fact that people go to Grand Canyon National Park in every generation makes it difficult for any single political leader to come into office and say, ‘This is a waste of resources.’ There would be an outcry—generation after generation has created its own experiences and memories and meaning there.”

The approach may also work for ideas, communities, and bodies of knowledge. Harvard economist and former Secretary of the Treasury Larry Summers argues one community’s decision to “set a precedent for generosity” by stewarding valuable resources can spark an intergenerational chain reaction. Venkataraman believes these strategies apply in the context of coronavirus. “A lot of us feel powerless but have more agency to make choices than we think: What kind of exposure we create for others. Whether we’re contributing to food banks that are shoring up families, or even doing video classes with a friend’s small child so they can work.”

Forward thinking, for all of us

As Venkataraman lists examples, my mind jumps to my favorite crêperie in New York, the Little Choc Apothecary. As someone with a long list of dietary restrictions and an affinity for pseudo-French cuisine, Little Choc’s gluten- and dairy-free crêpes are one of my most cherished pleasures. On March 23, Little Choc posted an Instagram announcement of its closure, accompanied by a plea for help: “We need your help to support our lovely staff, who, along with so many others in the hospitality industry, suddenly found themselves without a source of income. Please consider donating.”

Anyone who donated over $50 would receive 20 percent off meals for the year—“One-Year Homies”—and anyone who gave over $250 would get discounted meals forever—“Lifetime Homies”—both smart appeals to the sense of community the owners had built. Recalling raucous brunches with friends and afternoon tea with my mother, I raced to donate. They’d reminded me that I considered them an heirloom.

“We reinforce each other when it comes to thinking ahead and being able to make long-term decisions,” Venkataraman explains, drawing on research published by behavioral scientists at the University of Colorado, Boulder. “There are going to be stories of resilience from this time, and as much as we want to prevent as much suffering as we can, we should also be looking to those stories as sources of strength for whatever we face going forward. The book is called The Optimist’s Telescope not because I believe everything’s going fine but because I believe we have the insights and capability to do much better.”