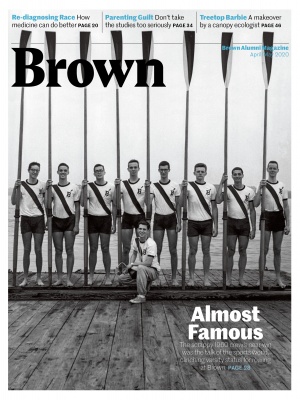

Stroke of Luck

How a team of club rowers from Brown, so ragtag they were dubbed “The Cinderella Crew,” almost took the national varsity championship in 1960.

“Rowing will become a University-sanctioned sport over my dead body,” Brown president Henry M. Wriston famously said. Then in 1960, the scrappy club crew pulled together so well that they almost won the most important race in college crew, landing themselves in the pages of Sports Illustrated, which called Brown’s performance “the biggest upset since David skulled Goliath.” The New York Herald Tribune noted that “if the race had been rowed in orthodox fashion, the boys from Providence might have taken it all.” But the eight “boys from Providence” that were in that shell were just happy to have placed. Here’s their incredible story told by oarsman John Escher ’61, who was in the four seat—and a surprise ending the teammates discovered 60 years later.

That the 1960 Brown club crew had even been invited to attend college crew’s top event, the Intercollegiate Rowing Championship, was something of a miracle. The Ivy League had existed for just seven years and Brown athletics had not yet made a favorable impression. Some even grumbled about whether Brown belonged in the league at all.

No one expected our club—which at that point was not even formally recognized by the University—would do anything to change that perception.

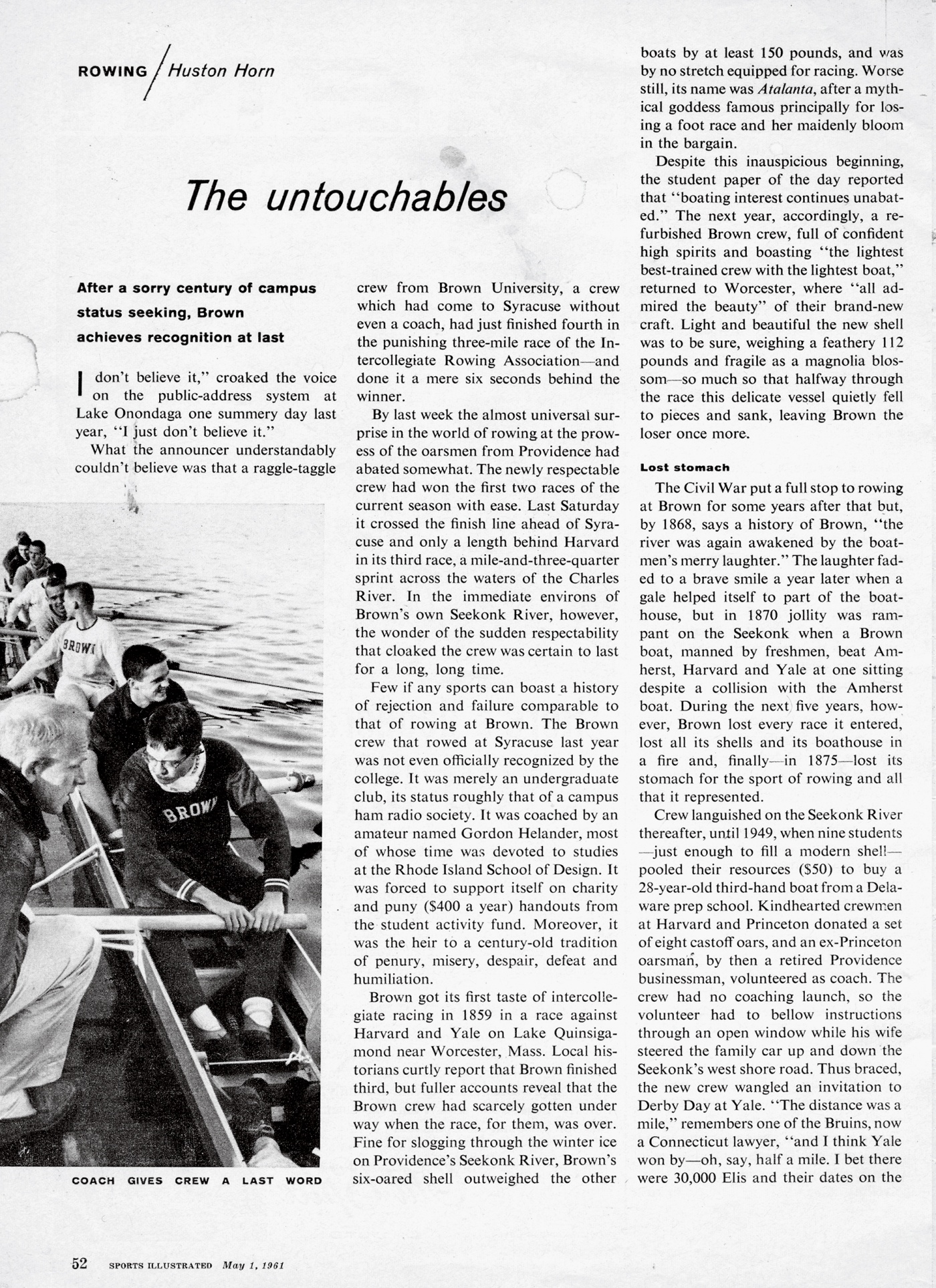

When I joined the Brown University Rowing Association as a freshman in the fall of 1957, generations of members had failed to extract so much as a penny from the University for equipment. The administration repeatedly dismissed crew as being too expensive and not worthy of varsity status.

We took to transporting our 65-foot racing boat, the Stein, on top of a teammate’s station wagon. This involved several oarsmen lying down inside the car and pushing their feet up against the roof to keep it from collapsing. The end of the boat trailed behind, supported by two toy wheels with a boulder wedged above them for ballast.

After our coxswain’s father learned with horror that we drove this swaying contraption, he gave us a sturdier pickup truck, although it still wobbled ominously.

For a coach, we had Gordon “Whitey” Helander, a former U.S. Marine and RISD engineering major whom someone found at a party and convinced to help us as a volunteer. Whitey had only rowed briefly at Syracuse, but he nonetheless whipped us into shape: no smoking, proper dieting, and no more driving down to the boathouse from campus. From now on, we had to run there and back. He also had a penchant for long distance, full-strength rows and had us glide the Stein out along the Seekonk River far into Narragansett Bay.

My sophomore year, we won the 1959 Dad Vail Regatta, a collegiate rowing championship for less-established crew programs, and we won again the following year and the year after that. We were able to recruit better athletes as the program grew. My sister had a friend, Bob Olson, who was returning to Brown from special forces black ops work in Berlin, and he told me he would try crew for a week if I agreed to jump out of an airplane.

I never had to make the jump but Olson stuck around as an oarsman, and going into the Intercollegiate Rowing Association Championship (known as the IRA), we had a tall and brawny crew.

Alas, as we began preparing for the year’s most prestigious regatta, Coach Whitey had to leave us for National Guard duty. We would have to go up against the biggest rowing powerhouses in the country with no coach. The press called us “The Orphans of the Seekonk.”

Fortunately, our most skilled oarsman, Bill Engeman, had a former high school coach who allowed us to train with his national championship schoolboy program. We rowed three miles at a time—the length of the IRA—and various high school crews would race against us at different points so that at every section we always faced fresh and fast competition.

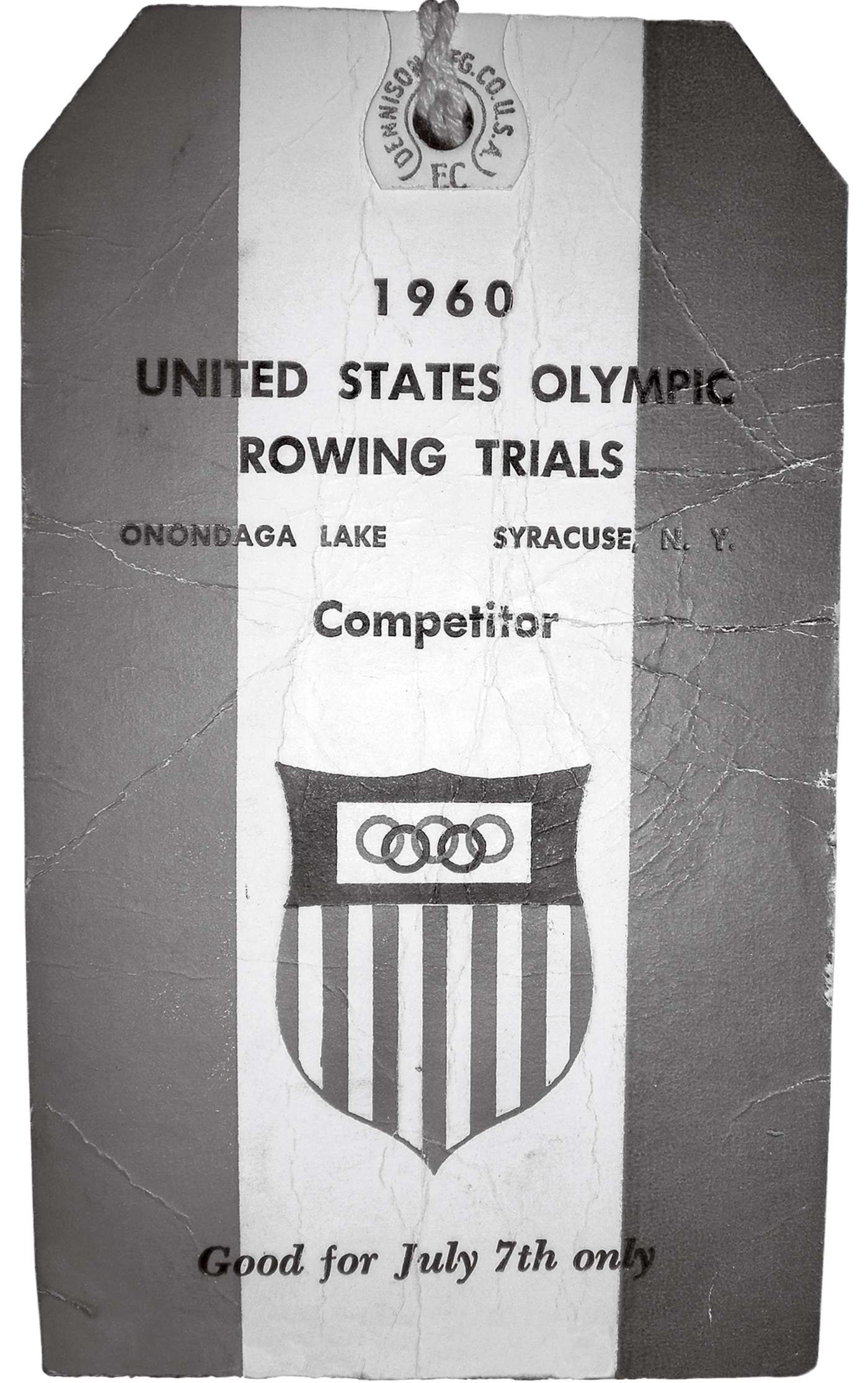

The day of the IRA was cloudless on Onondaga Lake in Syracuse. The flat water reflected every oar of the twelve boats in competition. I cannot remember in my four years as an undergraduate and later years as a crew coach a more smooth and perfect motion as we made our way to the starting line with soft strokes.

Cornell, of course, was the odds-on favorite to win, and their coach had won the IRA for the last four years. Observers expected that Navy and Penn would also be serious contenders.

We were dubbed the “ugly ducklings” of the race, lucky to even participate.

As the race began, we started out with ten lackadaisical strokes on purpose and fell behind the other crews except for Columbia.

Goodbye, Columbia.

Then we fell into a rhythm of long, hard pulls, about one every two seconds. Each stroke requires a hard push of the legs, like a double-barreled shotgun blast, and it was not uncommon for oarsmen to faint. A three-mile regatta is one of the most brutal endurance tests in sports, yet we held our form.

We relied on the coxswain, our psychologist and jockey, to guide and steer us. Normally, boats pass each other arduously, edging ahead of competition mere oarsman by oarsman, foot by foot, with the coxswain rallying his crew with notice of every incremental gain.

But that day, our coxswain, Mouse Mackenzie, took to yelling out whole colleges, we went by so fast.

“I’ve got Dartmouth, now give me Syracuse. I got em!” Mouse yelled. “Now gimme me Princeton! And Wisconsin! Yes!!!!”

The race’s announcer noticed Brown’s advance and assured viewers he would double check to make sure he was seeing things correctly.

“Get me Cornell...yes...and Penn...got ’em, okay!” Mouse cried. “We just passed the Naval Academy!...Washington’s all that’s left...wait! There’s something wrong with Washington!...their three-man’s passed out! Half a mile to go...get ’em!!!”

Yet as we were overtaking Washington, their coxswain decided not to steer. His veering boat pushed us towards shore, sending our bow to consort with the boulders and allowing California and Navy to recover and pass us in the final moments.

We were awarded fourth place in consolation, and the officials, who reviewed the result 14 times, kept asking us about filing a protest. Did we want to disqualify Washington and take third? Or rerow the three mile race? We voted not to, exhausted and exhilarated, feeling we had already proven ourselves.

After the press crowned us “The Cinderella Crew,” a nickname my dad had come up with and I’d printed in a newsletter, the University administration was forced to take notice. By the end of the year, President Barnaby C. Keeney declared that Brown would finally recognize crew as a varsity sport.

But we never stopped thinking about that regatta and whether we could have won. It took us nearly 60 years to figure out what happened. Studying the IRA records, our lead oarsman Bill Engeman noticed that there was no official entry for Brown’s time after third place Washington’s 16 minutes, two seconds. In the chaos of the conclusion, the timing of the regatta apparently became impossible.

Our boat never finished the race.