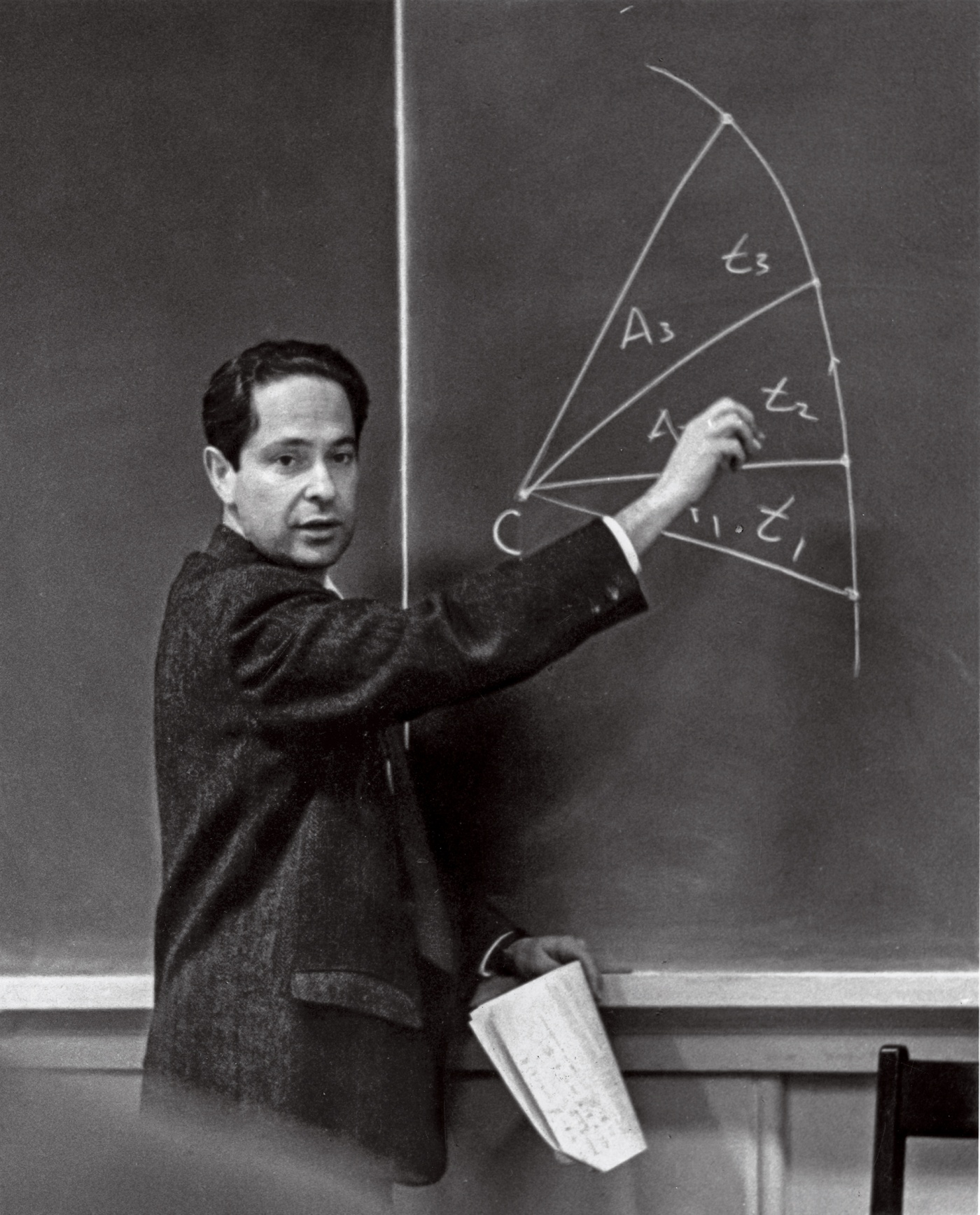

Father of the Open Curriculum

Meet the 95-year-old who narrowly escaped the Holocaust, became a Brown professor, then pioneered a style of teaching that paved the way for the University’s signature approach to education.

“I don’t think I was very much involved in the New Curriculum,” says Professor Emeritus George Morgan, who at age 95 speaks elegant English in a soft voice still tinged with the German influence of his native Vienna, from which he escaped at age 14, two weeks before Kristallnacht. In 1958-59, a decade before the Open Curriculum was launched, Morgan taught the first interdisciplinary course at Brown, with an emphasis on students directing their own line of academic inquiry. Let’s just say that his crazy ideas kind of caught on.

While the notoriously humble Morgan denies any direct involvement in the 1969 curricular reforms that have become Brown’s calling card, his CV and his students tell a different story. “[Morgan’s] educational philosophy inspired and strongly influenced both Maxwell and Magaziner and others of us on the committee,” says Ken Weiner ’72, who as a first-year student was part of the group tasked with figuring out how to turn the Magaziner-Maxwell Report into a university-wide curriculum. “You can trace every interdisciplinary program and institute at Brown to Professor Morgan’s influence,” Weiner adds.

Morgan was “the intellectual architect of the New Curriculum and the inspiration for many of us who participated in its creation,” agrees Michael Kilgore ’71. In February 1969, Kilgore and a classmate wrote a letter to professor Paul Maeder, chair of the committee tasked with mapping out curriculum changes, suggesting that first-year students take multidisciplinary courses called “Modes of Thought.” The idea became part of Brown’s New Curriculum. Where did it come from? “David Fraser and I were reading Alfred North Whitehead’s Modes of Thought in a George Morgan class.”

There are many places where a dotted line appears between Morgan and what is now called the Open Curriculum. Two of the three students on the Maeder committee studied with Morgan, as did eight of the 20 students who wrote the Magaziner-Maxwell report.

Morgan “kind of pioneered interdisciplinary thinking,” including “a lot of what we would eventually work on,” confirms Ira Magaziner ’69, one of the founders of the Open Curriculum. “He was ahead of his time, and certainly an inspiration for the New Curriculum.”

Educators across the country knew of his powerful influence, a line from Morgan’s 1989 CV suggests: “I have received and continue to receive numerous mail inquiries, requests for advice, etc. from universities, colleges, schools, and some corporations in the U.S. and abroad concerning interdisciplinary work,” Morgan wrote at the time.

The “University Course”

George Morgan came to Brown in 1950, recruited into applied mathematics, a department that Brown considered one of its “great jewels,” says former Morgan student Ken Ribet ’69, ’69 AM, a UC Berkeley math professor and the immediate past president of the American Mathematical Society. Morgan was quickly tenured and just as quickly began to want to broaden his scope of inquiry. As Ribet puts it, “here’s this guy who was hired as a brilliant mathematician and kind of abruptly declared that he had more important things to study.”

That’s pretty much how it happened, Morgan confirms: “As the years went on, I found that I couldn’t really get sufficiently interested in the things that other people in mathematics were interested in. It was all pretty abstract and not really having anything serious to do with what human life was about.”

But while math wasn’t cutting it anymore, Morgan didn’t see another discipline that fit his interests. “In order to study anything that had to do with how human beings live, the usual scientific approach seemed to me much too narrow,” Morgan says. “You can’t say very much about human beings without including the emotions. But when you do applied mathematics, emotions don’t exist.” Yet more human-centered fields like sociology and history weren’t much better, Morgan felt: “Because of the general climate of what was being admired,” he says, “they [the humanities] tried to be scientific too. And it seemed to me that this was just totally misguided.”

Enter the University Course. Morgan says he wanted to develop “a course that did justice to what it was like to be human.” His first one was called Modes of Experience: Science, History, Philosophy, and the Arts. “I was doing what became interdisciplinary without calling it that at the time,” Morgan says. And he’s adamant that the courses he taught not be called “Modes of Thought.”

“I deliberately called it experience,” he says. “Thought, whereas I admire it and it’s very important to what it is to be a person, there are other aspects of our lives—let’s call it roughly emotions, though that’s not adequate—which have to be paid attention to, also.”

Morgan took his idea to President Barnaby Keeney, who said, “Well, that all sounds very good, Morgan, but where would we put such a course?” Thus the cross-disciplinary “university course” designation. At the same time, according to Jeff Bercuvitz ’84, to whom Morgan told this story many times, “Morgan suggested to Keeney that in order to encourage students to learn material well outside of their ken, they ought to be able to take any and all courses at Brown on a pass/fail basis.”

Morgan didn’t sell Keeney on pass/fail at that point, but he did get the go-ahead for the course and started teaching Modes of Experience in the 1958-59 school year. Its course catalog description read like a harbinger of the Open Curriculum: “Sharp separation of disciplines ... are characteristic of our time,” it lamented. Modes of Experience would be different.

Morgan’s unorthodox approach didn’t go over well with some of his colleagues—especially not after his university courses became wildly popular. “The faculty by and large looked askance at what I was doing,” Morgan remembers. They “felt the students were becoming enthusiastic about something that was not real learning.” Morgan, who was eventually appointed as a “University Professor,” free from the strictures of any particular department, wasn’t just blowing up the boundaries between disciplines, he was turning pedagogy on its head by encouraging undergraduates to direct their own inquiry. Ribet reads from a final exam he’d saved since his undergraduate days that exemplifies the openness of the Morgan classroom. “Looking back over the course as a whole,” the exam directed, “explore what you now believe to be the most important things you learned.” The professor asked for rigor, but what you wrote about was totally up to you.

“You don’t just scotch-tape cognitive science to political science. You start with the questions and then pull in the different fields.”

“Students were highly enthusiastic,” Morgan says—and his work also turned heads outside Brown. According to Alexandra Morgan ’84, her father often told the story of someone from the Carnegie Foundation telling Keeney, “what a brilliant idea you had for that course!” “What course?” Keeney asked. “The course that George Morgan is teaching.”

Morgan next launched a new major in “Human Studies,” which Bercuvitz calls “a precursor to independent concentrations—students were able to concentrate on a critical question or theme rather than a discipline.”

Says Chuck Primus ’67, ’75 PhD: “What I got more than anything was how to think outside the box and think across the disciplinary boxes.”

History was on Morgan’s side. As Chaplain of the University Janet Cooper-Nelson said at an event celebrating Morgan last May, “His role and structural appointment to create connections across the curriculum beginning in the mid-50s are the shoulders on which Brown’s New Curriculum is built.”

Alfie Kohn ’79, a widely-known author and lecturer on education, psychology, and parenting, remembers that in Morgan’s class, students sat in a circle and got to choose both their own topic and whether to work individually or with others. “I’d never seen anything like that before,” he says. Yet as a scientist who felt that science alone wasn’t an adequate way to study the human experience, Morgan was engaged in “an intellectually rigorous critique of rationality,” Kohn says. And his approach to interdisciplinary study was equally rigorous. “You don’t just scotch-tape cognitive science to political science,” Kohn explains. “You start with the questions and then pull in the different fields.”

The Whole Student

The Big Questions about life and love that Morgan asked in his classes—with help from such thinkers as Rainer Maria Rilke (Letters to a Young Poet) and Martin Buber (I and Thou)—were perhaps a perfect way to ignite the intellects of undergraduates. But for many, the passion never waned. Last May 11, close to 100 of the professor’s former students came from all over the U.S. to celebrate their mentor—an event organized by Bercuvitz, Bob Cohen ’68, Jim Dickson ’68, Fred Marchant ’68, and Richard Narva ’68, with Alexandra Morgan and Cooper-Nelson. After a breakfast mixer and some live Mozart string quartets—Morgan has long been an arts lover—Brown graduates spanning more than 30 years gathered in a large room at the Brown Faculty Club. Sitting up against a wall at the front was a slim man in a brown suit who looked at least a decade younger than Morgan’s oldest former students. It was Morgan himself, who turned 95 that day but looked to be in his 70s. The professor didn’t want a birthday fuss, so the “Morganizers,” as they called themselves, managed to keep the milestone birthday a secret throughout the seven-and-a-half-hour event.

More than an hour was devoted to testimonials, with a line of former students waiting for their turn at the mic. Some were moved to tears as they remembered discussing seminal texts by Buber, Rilke, Elie Wiesel, and Austrian philosopher and priest Ivan Illich, among others. “My psych courses were boring,” said Steve Slaten ’75, now a psychologist. With Morgan, he said, he was able to talk about things that seemed more real.

“It was this life-changing experience,” says Michael Shadlen ’81, ’88 MD, a professor of neuroscience at Columbia University, of taking a class with Morgan. Shadlen got up to talk about the moment, during office hours, in which Shadlen made a dismissive comment about political activism and Morgan, in his gentle, Socratic way, helped him change his perspective—profoundly.

Martha Bebinger ’93, now a reporter for WBUR, Boston’s NPR news station, recalls her fear when she and a few classmates asked Morgan if they could study homosexuality in his class Between Man and Man. “Being openly gay was still fairly fringe, even at Brown,” Bebinger remembers. “Asking that homosexuality be taken seriously as an area of academic inquiry was scary.” But she says that Morgan did not seem to hesitate. He asked only “that we engage deeply with questions about the role of sexuality in community, relationships, and a deeper understanding of one’s self,” she says. The message she took was, “I respect you and this pursuit,” an acknowledgment that held “profound power.” Karlo Berger ’86 summed it up nicely in his testimonial: Studying with Morgan, he said, was the “first time I was encouraged to bring not only my intellect but my deeper humanity to my academic engagement.”

Morgan invited that “deeper humanity” to the table quite literally. He and his wife Barbara frequently had students over to their home for dinners—“I remember stirring polenta over the stove with Barbara,” says Ruth Loew ’72—that over the years morphed into potlucks. Says Weiner, “The Morgans introduced me to fine cheese and fresh local ingredients way before Alice Waters and Michelle Obama.” Sue Sturm ’76, a law professor at Columbia, says “pot luck dinners are a big part of what I do,” adding, “this is not done in law school.” But for Sturm, providing a place for her law students to build community is essential. After studying with Morgan, she says, “I started to really prioritize the questions of meaning and purpose.”

Ken Ribet, the Berkeley math professor, remembers getting a dinner invitation from Morgan in 1973, four years after Ribet graduated. “This has affected me profoundly,” says Ribet. “I keep up with my students in an analogous way, but it’s more along the lines of wishing them happy birthday on Facebook.”

According to Ribet, Morgan “was almost like a psychotherapist. He would listen very, very intently and made very few comments, and you were certain you were being heard but you wondered whether you would be equal to the intellectual rigor.”

Decades later, his students remember quite clearly the level of engagement they felt in Morgan’s classes. Dickson is a VP for The American Association of People with Disabilities whose resume includes crucial work on the passage of the Clean Air Act and a place in history as the first blind person to sail solo from R.I. to Bermuda. Morgan, he says, left him feeling “completely inadequate but also inspired. It was my first experience with the power and magic and glory of sitting with another human being who listened and asked powerful questions.”

Applied Ethics

For all George Morgan’s boundary-pushing, the professor was never exactly a hippie. “He had this kind of European dignified formality, somewhat old-fashioned and yet clearly not,” remembers Breuer. So where did the progressive attitudes come from?

Morgan himself figures it was probably his experience as a refugee from the Nazis. His father was a lawyer in Vienna and a client tipped him off that, since they were Jewish, they’d better leave. It was 1938. Young George and his father went every day from embassy to embassy, looking for a path out of the country. They wore gold stars on their clothing, as the Nazis required, and their identification papers were stamped each day with swastikas. Finally, through his father’s connections, the family ended up in Montreal. Kristallnacht, when many Jews were killed and tens of thousands were taken to concentration camps, occurred just two weeks later.

Morgan was 14 at the time. His father, who did not speak English and who had suffered the first of a succession of strokes, would have had to repeat law school in order to practice in Canada. But his previous success as an attorney gave the family an opportunity. Back in Vienna, a bankrupt client had paid his debt to Morgan’s father by giving him commercial sweater knitting machines. After the Morgans fled Vienna, Mitzi, a devoted household employee who was not Jewish but who had donned a yellow star in order to continue working for the family, packed up the machinery and shipped it to Canada for her former employers.

Morgan found himself setting up and managing a knitting factory that soon employed 20 French- and English-speaking Canadians, while he torturously learned English from a schoolmaster with a thick Scottish accent. This trial by fire, Morgan says, “required me to learn things that I would never have learned just being at the University. How to get along with very different kinds of people.”

Morgan’s creative mind showed itself at that early age. According to Alexandra Morgan, the knitting machines posed a particular problem. “If one thread snapped, the whole machine would be entangled in seconds or minutes, and the machine would be out of production.” So Morgan invented a spring that would stop the yarn from unraveling in that situation, and installed it throughout his factory. A visiting sweater factory owner saw the device in use, asked the boy about it—and patented it himself.

“Morgan wanted to show students a way of being in the world which would prevent them from ever waking up in the middle of Nazism.”

Morgan’s life as a wealthy inventor may have been thwarted, but he finished high school with honors, got an engineering degree at McGill, a PhD at Cornell, and landed at the Applied Mathematics program at Brown. Then, according to a 1995 BAM article, Morgan took a sabbatical in 1956-57 to “wrestle with his intellectual conscience.” As he explained it, “I wanted to make questions of human existence more central to my work, because learning and life have to go together.”

For Morgan, says Cooper-Nelson, “the human architecture of violence is the core intellectual idea.” How were the structures of violence and oppression put into place? “The applied part of George’s mathematics led him to the applied part of ethics,” says the chaplain. “George sought... a place to teach that was not constrained by department but tethered to the full intellectual enterprise as it might ameliorate human suffering and create human good.”

Morgan “brought his heart to the table as well as his intellectual passions,” says Alicia Korten ’92, who took his course The Threat of Nuclear War. “He was clearly so passionate and at some times distraught at where we were going at the time,” seeing a trend towards “the continuous concentration of power.” At the core, Korten says,

“he’s motivated by love for his students and the planet.”

According to Cooper-Nelson, even Morgan’s focus on interdisciplinary study came from a moral imperative. “The idea of Nazi doctors being so interested in what happens if you immerse someone in hot water that they lost sight of humanity—he wanted you to never be able to be that ‘disciplinary,’” she says. “He wanted you to notice things and to understand how the doing of life could be moral or not, could be good for you and others or not, and that it was up to you.”

Though Morgan was not religious, Cooper-Nelson says, “He wanted to show Brown students a way of being in the world which would prevent them from ever waking up in the middle of Nazism. He felt honor-bound, morally bound, to prevent it. His idea of how to prevent it was to create people who had a moral compass.”

At the gathering of Morgan’s students on his 95th birthday, Xena Huff ’90, ’98 AM declared, “What we’re doing now [as a society] is broken.” The answer, she felt, was the way of thinking and the type of community inspired by Morgan.

By “broken,” Huff says she meant everything from climate change to race relations to our dependence on automobiles. Before attending the event, Huff read Morgan’s book, The Human Predicament, which outlined, she says, “The mathematics and science of oneness.” Like many of Morgan’s students at the event, she expressed confidence in the power of his teachings; that if proselytized, they might change the world. In a phone interview later, she admitted, laughing, “it sounds like a cult.”

“There was a bit of a cult of personality to him,” Breuer said. “He did inspire that with people. He just had an aura.” Even those of Morgan’s students who attended Brown after the Open Curriculum was already in full swing—when Morgan’s style of student-led learning and discipline-mixing had become an essential part of the University as an institution—seem to have a particular enthusiasm for whatever more it was that Morgan did in his classes.

The difference between the curriculum Morgan helped to inspire and the teaching he did himself seems to be the emphasis on intellectual inquiry into human emotions—and on personal connection and community, and on the moral aspects of taking a stand. Decades later, his students are still fired up and looking for ways to bring The Morgan Way to Brown, perhaps through a funded chair or a lecture series, to inspire today’s students the way they had been.

“Being with a group of people who are trying for something different, and believe in it,” Huff says, “it recharges you with energy.” Enough energy to create a new curriculum, and perhaps even a better university—and a better world.

Open Curriculum in Real Life

How has the Open Curriculum served those who have lived it, at Brown and in their lives since? We asked, you answered.

Life choices

In 1969 I began my third year enrolled at Tougaloo College, and when I returned to Rhode Island after that semester in the South I found that changes had occurred on campus destined to redefine my life: more choices, new grading options, and greater freedom to explore the wealth of course offerings at Brown. Pre-med by declaration but a humanities major at heart, this was the first opportunity I’d had in my young life to reinvent myself in my own image. I took it.

Unencumbered by prescriptive and restrictive requirements, the courses that rose to the top of my new list were no longer of the math and science type but more related to art, economics, and education. Economic injustice had always tormented my sensibilities, if not my soul; now I could gain a real perspective on its depth and extent. Music had always been a bystander sport for me; Brown now encouraged me to compose my own music as an aesthete rather than an observer.

My metaphor for education had always been that of a bottle being filled. With Reginald Archambault holding court at our Socratic seminars on the various conflicting theories of education, my mind expanded into realms of reason and purpose I had never experienced while mired in the linearity of organic chemistry and slide rule physics. That spring and the following year were transformative. In the ’70s we called this “finding yourself.” Looking back, it comes across more like growing into who you really are—an enlightened renewal.

Ira Magaziner didn’t intend to revolutionize my life. He just wanted Brown to trust that its undergraduates could make worthy decisions about their academic path. No one can deny the power of having choices and our ability, given the opportunity, to make ones worthy of a lifetime.—James Pesout ’71

Space monkey

Forgive me for not joining in the celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Open Curriculum. As a member of the Class of ’71, I was caught squarely in the mess that preceded and followed this massive change. In a nutshell, my freshman and sophomore years were devoted to racking up meaningless required courses from the old curriculum. Having completed them on time, I found that, entering my junior year, I was now in uncharted territory that no one—not me, not faculty, and not the school’s administrators—had a clue about! My choice for a concentration—Communications—was turned down, despite the fact that I was the music director at WBRU and worked there full time during the summer months. Of course, no academic credit was given for those activities during my four years at Brown. Nonetheless I went on to work in broadcast media—both radio and network television—as talent, producer, and DJ for the next ten years. What has followed is a lifetime in media work of all sorts, including print, video, corporate communications, and digital media. So thank you WBRU for providing real value for me during those turbulent years. I’m happy for those later classes who may well have benefited from the Open Curriculum once the faculty and administration actually figured it out. As for me, well, I’m like one of those monkeys they shot into space in the early days of NASA. They knew how to get them up there; just not how to get them back down. —Paul Gregutt ’71

Physics and poetry

I was really good at math and science and was frankly mediocre in writing and English.

I elected to be a ScB physics major. It was 1970 and I totally expected to be given a list of courses to take throughout my undergraduate career. When I got to campus, I was told that I should consider some MoT courses. What the heck?

What does Modes-of-Thought mean? Well, I elected to do an expository writing class—Pass/No Cookies. As I noted, I really needed to expand my horizons in writing. I struggled! Somehow, I even wrote a poem. I have now written nearly 600 technical papers. The MoT courses served me very well. I learned how to think and they even helped me learn how to write better. It really is worth taking risks to step a long ways out of one’s comfort zones if you want to do something interesting. —Rick Ziolkowski ’74

5-year plan

The Open Curriculum (or the New Curriculum as we called it then) was the main reason I chose Brown over the other schools that accepted me. I didn’t have any lofty aspirations of it being key to my success. I am naturally self-directed and just wanted control over my own education. And the absence of phys. ed. or foreign language requirements certainly didn’t hurt.

As an engineering major I found the New Curriculum to be a cruel joke on students concentrating in engineering or science: the curriculum in theory offered all these wonderful, fascinating opportunities, but all you got was one elective per semester and it had to be sandwiched in around all your required lectures, section meetings, and labs.

Luckily my parents could afford to pay for an extra year and I enrolled in the 5-year ScB+AB program, which allowed me nine more course slots. All I had to do was pick an AB that matched the courses I wanted to take anyway. I became interested in urban planning and ending up assembling a program that looked an awful lot like engineering-plus-what-we-now-call-urban-studies (the latter did not exist as a major back then). It was basically like an independent concentration without officially being one.

My social/emotional life at Brown was rather lonely and sad, for personal reasons that don’t matter for talking about the Open Curriculum. But that curriculum helped keep my Brown experience so rich and exciting that I never considered dropping out, which I otherwise might have done. —David A. Ernst ’74

S/NC success

I decided in the first few days of being at Brown that I would conduct a personal educational experiment with the New Curriculum: I would take two classes for grades and two classes S/NC the fall of my first year and see how I learned best: either receiving a grade from the professor or providing my own self reflection (S/NC). To my amazement, I enjoyed the learning and did much better (higher grades) in my two S/NC classes (with far less stress, which quieted my dyslexia symptoms considerably) than I did in my two classes for a grade. The findings of my self-conducted experiment sent me headlong into S/NC territory and I never looked back.

My official Brown transcript has two grades and twenty-eight S’s! I earned a graduate degree, with honors, from Rhode Island School of Design in the Art and Design Education Department. My graduate studies focused on the qualitative assessment of the educational effectiveness of nontraditional educational settings. Today, I continue to be a successful artist and educator. My experience at Brown, taking full advantage of the New Curriculum, began a lifelong inquiry into creativity and learning which continues to captivate my personal and professional passions today. —Milisa Galazzi ’88

Sea of stars

I took all the classes outside my major pass/fail and ended up with a stream of S’s for “Satisfactory” on my transcript…. My academic experience at Brown was challenging. I didn’t find my right fit or flow until senior year. I endured classes rather than being energized by them. And I felt myself slipping into a self-perception of failing, even if I factually passed every class.

It’s been 30 years and this past week I was reviewing my Brown transcript. I was frustrated by the lack of description in all those satisfactory ratings. I felt I had probably chickened out. I didn’t want to face a deficiency in myself I experienced at Brown head on. In high school, grade school, I was the brightest star. At Brown, I was just one in a sea of them, and more often than not outshone by those with more luster. I was not excellent at Brown, probably more like below average. And so the S’s establish that in striking plainspeak, more than I would like. I would rather see the ragged, unruly steps of my educational struggle, C then B then C then an A- reprieve, C again. I hate to see all those S’s lull into obscurity what was a poignant, challenging, changeful life passage—and one where I was ultimately victorious: “S” for survival. —Lisa Gage Star ’90

Trust and empowerment

[As an undergrad] I was very interested in figuring out how the diaspora in Africa were connected—who are we as people. There wasn’t a course for that, so we created an independent study called “The Ties that Bind” or something like that. I continue to find that’s such a fascinating area as I look at hip hop, music, the arts, and all these things that are co-created across these boundaries.

Because Brown trusts you in your learning, you bring that into education. As an educator, I feel like I have the ability to open up to students and support their learning in the same ways. Being given the power to nurture my own learning, I feel like I am able to empower the young people I work with to nurture their own learning, to design their own understanding and creativity as well. —Nadirah Moreland ’94

Pieces of home

When I was choosing a college, I knew I had to choose somewhere that was worth leaving my Native community, my tribe, and my people for four years. Moving from the reservation that I lived on for 18 years, disconnecting from the culture and leaving my entire family back was the hardest decision I’ve ever had to make. But I’m glad that I did.

I chose Brown for many reasons, but one of the biggest was the Open Curriculum. It has allowed me to build my own learning experience, giving me the power and agency to take courses I loved in Ethnic Studies, while simultaneously earning a Political Science degree to become a powerful political voice to change the world for Indian Country.

I am able to find little bits and pieces of home all over this campus, like within Native and Indigenous Studies at Brown, the Brown Center for Students of Color, the Ethnic Studies Department, and Natives at Brown.

When I’m in the kitchen of our Native House, making stew and frybread with my Indigenous friends, cracking jokes and laughing hysterically, I feel closer to home than ever and realize that Brown is where I am supposed to be. And during our Indigenous Peoples’ Day celebration, where we gather to honor the Indigenous peoples of this land and reject a colonial holiday that celebrates the genocide of my people, I am reminded of just how special of a place I am at, and the power that I hold to continue shaping this University into a better place for me, and people just like me. Shu’-’aa-shi nin-la (thank you). —Savanna Rilatos ’20, Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians