Open Minds

At some point, it became a little illogical to refer to Brown’s signature course of study as the “New Curriculum”—perhaps when it reached a point when it was older than most students.

But the fact that what’s now known as the “Open Curriculum” not only survives but thrives a half-century into its existence is surely testament to its continued freshness, its adaptability, its capacity for reinvention and exploration. It may have been of the moment when it was instituted back in the 1969-1970 academic year, when college students everywhere were challenging authority, but it remains just as relevant now.

Ira Magaziner ’69, a student co-author of the report that launched the curriculum, says that’s partly because its foundational principles are timeless.

In the ’60s, he says, there was an explosion of knowledge and a growing sense that traditional curricula and disciplinary boundaries were becoming less relevant. To address that, organizers “looked at the history and philosophy of education, both historically and currently, and came up with something that was rooted in that. In other places, it was ‘let’s study the Vietnam War.’ We thought that was too topical. We weren’t against it, but it didn’t define a philosophy of education.”

Most people who’ve spent any time on campus know the broad outlines of the curriculum they came up with: An emphasis on independent study, cross-disciplinary exploration, and self-direction. No required courses or distribution requirements outside of individual concentrations. And no failing or plus/minus grades, just letter grades or satisfactory, or else no credit.

Rashid Zia ’01, dean of the college and a member of the steering committee observing the curriculum’s 50th anniversary, says those are just the rules. The heart of the grand new project—the philosophical underpinnings and world view, and the part that he says embodies its fundamental optimism and capacity for constant evolution—rests in the Open Curriculum’s Statement of Educational Principles.

“At Brown University, the purpose of education for the undergraduate is to foster the intellectual and personal growth of the individual student,” the statement reads. “The student, ultimately responsible for his or her own development in both of these areas, must be an active participant in framing his or her own education.”

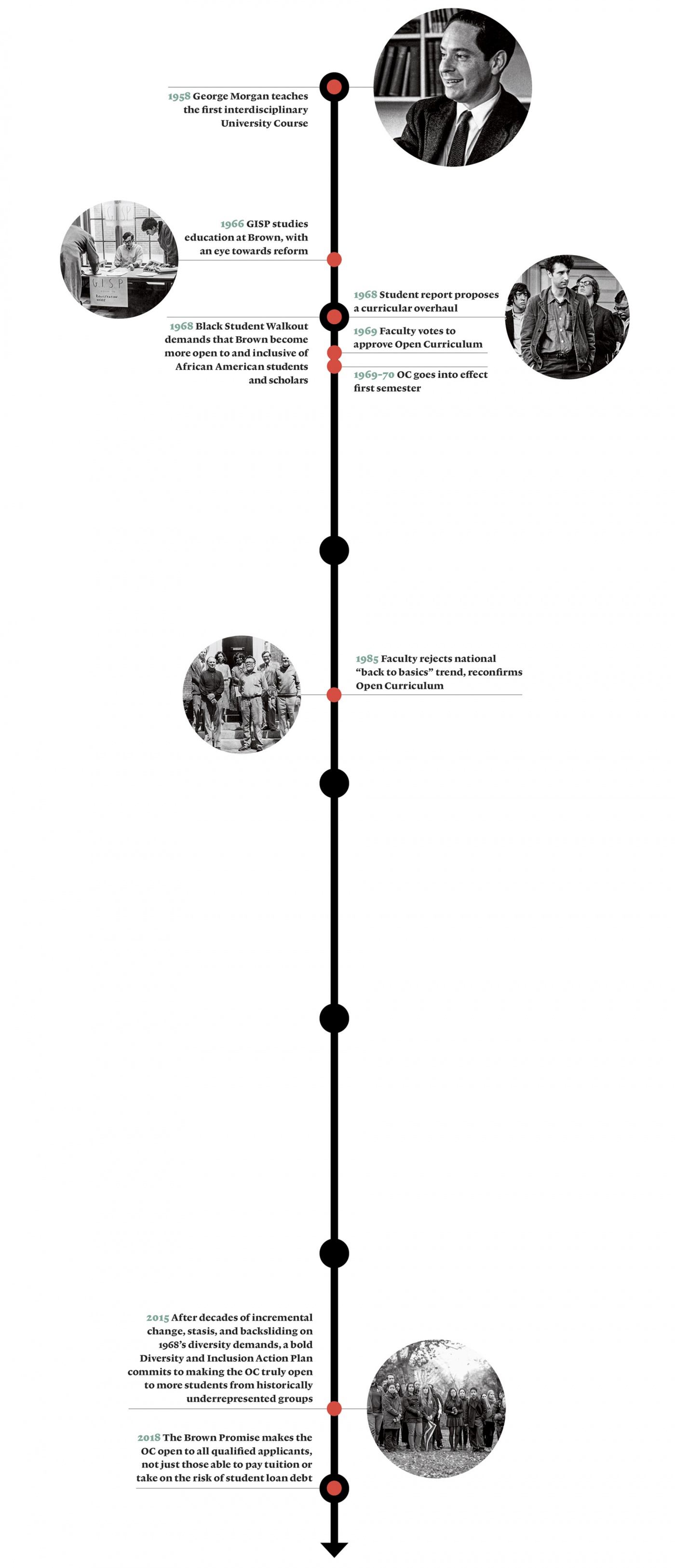

The process of creating the document was a long, inclusive one. It began in 1966, when Magaziner and Elliot Maxwell ’68 created a Group Independent Study Project (GISP), including 25 students and faculty advisors, to rethink teaching and learning at Brown. A separate, administration-sanctioned committee headed by political science Prof. Newell Stultz was formed a year later, which would recommend that students be allowed to design their own courses of study and take classes pass/fail. Another University committee, chaired by engineering professor Paul Maeder, followed.

In 1968, Magaziner, Maxwell, and 18 other students authored a 400-page report titled “Draft of a Working Paper for Education at Brown University.” That launched an extraordinary period of grassroots organizing and debate, ending with more than half of Brown’s undergraduates signing a petition to adopt the report. On May 7, 1969, the faculty recommended the elimination of distribution requirements, the introduction of cross-disciplinary “Modes of Thought” courses, and the option of receiving letter grades or taking classes satisfactory/no credit. The next day, it approved the Statement of Educational Principles, cowritten by students and faculty, which combined ideas from both groups and still lives in the faculty rules and regulations.

One existing trend that set the stage was that Brown had been starting to move in this direction anyway, according to John Thelin ’69, a university research professor at University of Kentucky and author of the book Going to College in the Sixties.

“What you had at a lot of campuses, including Brown, was that apart from changing the whole curriculum, there already were some streams of innovation. Students and professors could suggest new topics, independent studies,” Thelin says.

At many places the innovation came at the margins, he said, but Brown was distinctive in that these changes took center stage. Lots of students in that era were focused on intergenerational change, but “whereas at many campuses that energy would have gone into external politics, it so happened that at Brown it focused on changing the world right in front of you.”

Another factor was the widespread buy-in. Magaziner says proponents organized very carefully among students, “dorm by dorm, group by group,” and engaged the faculty peacefully.

The curriculum has changed little since its birth, even at times when broader trends directed other institutions more toward tradition. In the 1980s, when schools across the country were going back to basics, adding more requirements and refocusing on a core set of knowledge and skills, Brown held firm. After studying the issue for two years, Brown’s faculty concluded that “forced enrollment in particular subjects” often leads to “minimal performance rather than true and lasting knowledge of a subject,” according to a 1985 report in the New York Times.

There were a few changes during that era though, including an increase in the number of courses required to graduate from 28 to 30 courses and a new writing requirement. The University has also continually looked at ways to improve advising to help students navigate their many choices. And could the curriculum have been truly “open” back in 1969, when students of color were so underrepresented, when LGBTQ students were without the protection of even a University nondiscrimination statement, and when admission favored those who could pay? The plan for the black student walkout hit the front page of the BDH the same day the Maeder committee was announced. Since then, the University has gone through many reforms intended to make the Open Curriculum open to all.

Today, the Open Curriculum remains a central element of the Brown brand, and also a key to attracting the sort of students that Magaziner, Maxwell, and company envisioned thriving under the system way back when.

“What we were trying to do was educate leaders who were going to be disruptive. We wanted students who were going to be questioning of established views,” Magaziner says. “That’s rooted in the theory of human progress. Every new generation questions [what came before], and tries to improve upon it.”