A deep-sea explorer, a particle physicist, and a cryptographer—it sounds like the set-up for a groan-worthy joke.

It’s actually a cross-section of Setec Astronomy, a team of elite puzzle-solvers who compete annually at the MIT Mystery Hunt. One of the world’s oldest and best-known puzzle hunts (established in 1981, it’s been called the “Olympics meets Burning Man for a specific type of nerd”), the annual event brings thousands of people to Cambridge each January in hopes of deciphering complex puzzles to locate a hidden coin.

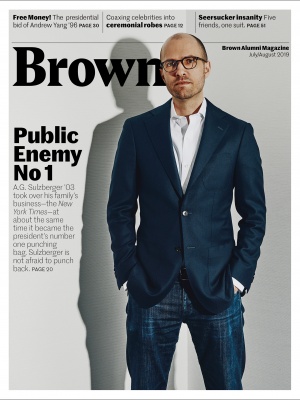

Setec Astronomy’s roster includes Dan Katz ’05 ScM, ’09 PhD, a senior lecturer in math at Brown, and Alex Rosenthal ’08, an editorial producer for TED Conferences (left and right, above). For Rosenthal, puzzling runs in the family. His mother, a national crossword champion, asked him to join her Mystery Hunt team when he was a junior at Brown. Katz started competing even earlier, as a high school junior. Since then, he’s participated in more than 20 Hunts—eight of which he won, making him perhaps the most decorated Mystery Hunter of all time.

Each hunt has a theme, from Carmen Sandiego in 1999 to Inception in 2016. This year’s, designed by Setec, commemorated the 100th anniversary of the Great Boston Molasses Flood. The initial puzzles are posted online and people get cracking. Teams can be any size, but the competitive ones generally number between 50 and 75. Solvers work nonstop for upwards of 50 hours, unraveling smaller puzzles that unlock bigger-picture “meta” puzzles—which, in turn, lead to a “meta meta” puzzle that reveals the location of the coin. The brain-teasers come in all varieties, from rebuses to ciphers to Japanese logic puzzles.

The prize? Writing the next year’s puzzle. Setec Astronomy won in 2016 as well as 2018 and reports that constructing the puzzle takes most of a year. (Rosenthal’s contribution to this year’s hunt, for instance, was a text adventure puzzle that took him 100 hours to devise.) The team starts with the final answer and works backwards, editing and testing each others’ puzzles to ensure they’re both fun and solvable.

A well-constructed puzzle ends with what Rosenthal calls the aha moment. “It happens in an instant,” he says. “You’re looking at something, and then suddenly you have this insight that changes the way you look at it. And then it’s this flood of relief—I got it!”