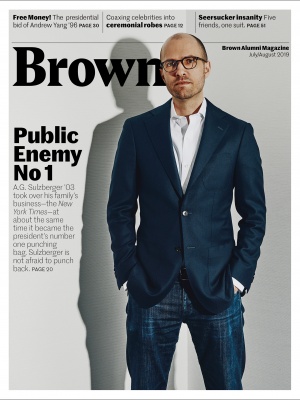

Arthur Gregg Sulzberger ’03, publisher of the “failing New York Times,” was once uncertain he wanted to be a journalist at all. But after years in the reporting trenches, he took over his family publication which—far from failing—has actually added positions. A year into his new role Sulzberger talks about the future of the flagship newspaper.

After graduating with a degree in political science, Arthur Gregg Sulzberger ’03, scion of the country’s most powerful newspaper family, turned to one of his greatest passions: ocean conservation. He traveled to the Galapagos Islands, in Ecuador, to help monitor the lobster catch and, incidentally, to “lock in” his Spanish.

While he was there, Tracy Breton, a Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist who’d taught him advanced feature writing at Brown, urged him to apply for a two-year internship at her home paper, the Providence Journal. Sulzberger recalls: “She made the best pitch I had heard: ‘Look, you’re good at this, you like it, and you should give it a shot. If it turns out it’s not for you, then you’ll have answered a big question that otherwise might hang over you in your life.’ ”

Sulzberger answered the question for himself. At 38, he is now answering it for a far bigger audience: the New York Times’s growing newsroom, an embattled media industry, and even President Donald Trump. After years of apprenticeship at regional newspapers and the Times itself, Sulzberger took over as Times publisher Jan. 1, 2018. He has since made news by chiding Trump for his “divisive” and “dangerous” media-baiting rhetoric. Closer to home, he is leading the Times’s efforts to become an increasingly digitally-focused, subscriber-based news organization—a shift in direction aimed at ensuring that the paper will survive and thrive (if not necessarily on paper) even as newspapers around the country continue to founder.

“A.G. is this bridge between the generation that he started with at these print papers and the generation that is more and more inhabiting our newsroom now and will propel us forward with digital skills, digital savvy, innovative instincts. He may be one of very few figures who have legitimacy with both groups,” says Carolyn Ryan, a Times assistant managing editor who, as metropolitan editor, was formerly Sulzberger’s boss. Now a good friend, Ryan says that she has “watched him, from the moment that he came in here, look around and soak up the place, the people, and what needed to change. And he has thrown himself into that adventure.”

Martin Baron, executive editor of the Washington Post, credits Sulzberger with having “both a soul and a spine.” His soul “is very much on the journalistic side of things,” Baron says. “He understands that the reason people are drawn to the Times is the quality of the work, and that that’s absolutely central to the business proposition as well.” The spine, he says, has been evident in Sulzberger’s “cool-headed” but “firm” encounters with the President. Baron notes approvingly that Sulzberger also “understands the need for journalists to adapt to the new ways that people are consuming information—not just adapt to it, but actually embrace it.”

“He was eccentric as a kid for sure,” Dolnick remembers. “He would only eat white rice, yogurt. There was a sense of not being swayed by peer pressure, the herd. He couldn’t care less. And it would manifest itself in weird ways: ‘You guys like pizza; I think pizza’s gross. I’m not going to the pizza party.’ You can see strains of that as an adult in much more meaningful ways.”

David Perpich, Sulzberger’s other cousin-competitor—he now heads the company’s product-rating site, Wirecutter, and sits on the Times’s board of directors—says he always admired Sulzberger’s “ability to read between the lines.” Though Sulzberger was something of an introvert, Perpich says, “he always was the leader of the pack of his friends.”

Dolnick says he and Perpich “were utterly confident [Sulzberger] would thrive in this job.” Still, “it’s been extraordinary to see him step into this role, and how quickly he has done it —that in his first year, he’s going toe to toe with the president in the Oval Office, upholding the values of the First Amendment and the free press in a way that makes the entire industry beam with pride.”

None of this was inevitable, though to an outsider it might have appeared so.

Sulzberger was, after all, the great-great-grandson of Adolph S. Ochs, the son of German Jewish immigrants, who in 1896 bought what was then (in reality, rather than presidential rhetoric) the failing New York Times; the great-grandson of Arthur Hays Sulzberger (who married Ochs’s daughter, Iphigene, and thus became Times publisher); the grandson of Arthur Ochs “Punch” Sulzberger, publisher from 1963-92; and the son of Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr. (“Pinch” to detractors, or more fondly, “AOS”), who succeeded his father as publisher in 1992 and saw it through the first upheavals of the Internet age.

Sulzberger—“A.G.” to his colleagues, “Arthur” to his intimates—was the heir apparent, though he would face competition from other talented fifth-generation members of the Ochs-Sulzberger clan. But he was far from certain that he wanted the publisher’s mantle—uncertain at first that he even wanted to be a journalist. “It just felt like too predictable a path,” he says in the course of a nearly two-hour-long interview at the Times’s Renzo Piano glass skyscraper in midtown Manhattan.

Sulzberger was drawn to politics—campaign work rather than political office, he says. An avid outdoorsman, he also contemplated a career as an environmentalist. He regularly organizes whitewater rafting trips, and he and his bride, the radio producer and reporter Molly Messick ’03, led a five-mile night hike through muddy woods to the family home in New Paltz, N.Y., following their wedding reception last fall.

Snapshots of Sulzberger’s wife and infant daughter, his maternal grandmother’s abandoned home in Topeka, Kansas, and favorite landscapes adorn a bulletin board in his unprepossessing office. An antique reading table displays issues of the print newspaper, and Sulzberger proudly points out the range of subjects and datelines on the front page. Industry analysts credit recent digital subscription gains at the Times, the Washington Post, and other news organizations to the “Trump Bump”—intense interest in coverage of the administration’s scandals, outrages, internecine quarrels, and more. But Sulzberger sees the company’s game plan as far broader.

“Not everything is politics—we cover the world,” he says. “We’re doing more long-form investigative reporting than we have at any point in our history. Why is it that, as we became more digital, we went back to that old-fashioned model, too? It’s because our strategy has become really clear inside the company: Once you say you’re a ‘subscription-first’ company, what you’re actually saying is that you need to make something so good that it’s worth paying for in the presence of free alternatives.”

In recent years, plummeting print advertising and circulation have caused most newspapers to slash their staffs and narrow their editorial ambitions. The overextended Times company suffered its own financial setbacks, serious enough that some commentators predicted bankruptcy. In response, says Eileen Murphy, the Times’s senior vice president of corporate communications, “the strategy was to pare the company down to its core.” After selling off many of its assets, including nine local TV stations, the Boston Globe, and other regional newspapers, and erecting a metered paywall for its digital content in 2011, it maintains its heftiest-ever newsroom of 1,600 employees, reporting from more than 160 countries. The large globe in a corner of Sulzberger’s office no doubt comes in handy.

“The trajectory of the business has been really good,” Sulzberger says, though the majority of revenues still derive from print. The 2018 Annual Report shows the Times’s digital revenues climbing to $709 million (on pace to exceed the company’s $800 million goal for 2020), with subscriptions, combined print and digital, topping 4.3 million. The goal for 2025 is 10 million subscribers.

A few days after the interview, the paper added to its historic trove of Pulitzer prizes with awards for editorial writing and explanatory journalism. The latter prize recognized an 18-month project that detailed a Trump family history of tax dodges that the story unambiguously labeled “outright fraud.”

“When I started as a journalist, I had this revelation that six months or a year into either politics or journalism, you would never, ever consider going into the other,” Sulzberger says. “Because six months in as a journalist you’re just shocked by the amount of moral compromise that you see in politics, and six months into politics, you’re shocked by how little the journalists actually know.”

At Brown, Sulzberger worked briefly on the Brown Daily Herald, but Breton’s class was more pivotal to his eventual career choice. “It was smart, rigorous. It demanded real work that could not be shortcutted with intelligence and a sophisticated turn of phrase,” he recalls. Breton, who remains a close friend, remembers Sulzberger as “very ambivalent about a career in journalism,” but also “a very good reporter, a very elegant writer, very detail-oriented,” as well as “very curious about how everyday people live their everyday lives.”

The course was graded “satisfactory/no credit,” but Breton gave letter grades for assignments. And on the one occasion Sulzberger received less than an A, “he immediately asked me whether it would be OK to do a rewrite,” she says. He passed up senior week activities to re-report the story. “Arthur doesn’t want to do anything in a less than stellar way—that’s just the way he is, whether it’s kayaking or journalism,” she says.

At the Journal, Sulzberger covered the town of Narragansett, R.I., and became hooked on reporting. “He had perfect news instincts. He just knew when he had a good story,” says Carol J. Young, the retired deputy executive editor. She remembers an anniversary piece on the polio epidemic and a story on the local Lions Club’s refusal to admit women as members. “One of the local power brokers threatened him that if he talked about the women’s issue, he would personally ruin his career in journalism for life,” Young says. “[The man] had no idea who he was. That was the kind of thing Arthur would never have made a point of telling anyone. He did share [the threat] with us. We all got a big laugh out of that, and ran the story.”

After the internship, in 2006, Sulzberger was offered a job at the Journal but moved instead to the Oregonian, in Portland, to report on county government and “see a bit more of the country.” Approaching his beat with investigative zeal, he uncovered “a government … in a cycle of pretty profound dysfunction” and a sheriff mired in scandals that included having lied about an affair with the governor’s wife. Les Zaitz, who shared bylines with him on the sheriff stories and now publishes and edits a rural weekly, remembers: “Arthur was relentless. He would spend hours trying to track down one person who could give us one detail.” The sheriff ultimately resigned.

Sulzberger says he was excited by the prospect of a new beat covering Oregon state government. But word of his promotion spurred an email from then–managing editor Jill Abramson recruiting him to the Times. Sulzberger says he had “mixed feelings,” wanting “to succeed on my own terms” and not “jump into an environment where I might not be ready.” Over drinks in New York, he sought advice from Stephen Engelberg, a former Times investigative editor and Oregonian managing editor who had helped found the investigative site ProPublica. As Sulzberger recalls the conversation, Engelberg reassured him of his talents and said he would be judged on his work, not his name.

Sulzberger thrived at the Times, reporting initially for the city desk. “He’s very observant, very astute. You sometimes don’t realize [that] because he can be a little bit understated,” says Ryan, recalling an offbeat story he wrote on two courthouse spectators at the fraud trial of the socialite Brooke Astor’s son, Anthony Marshall. “It’s sort of emblematic of the way he observes the world: He can see center stage, but he also sees what’s happening offstage.”

Dolnick, who had been a New Delhi–based foreign correspondent for the Associated Press, was hired a few months after Sulzberger, in 2009, and the cousins “developed a real friendship around the struggles of being young reporters in this incredibly intimidating place,” Sulzberger says.

In 2010, the publisher’s son relocated to Kansas City to cover the Midwest for the Times (as a longtime vegetarian, he dubbed it a “Mecca of meat” in a first-person piece). “Reporting out of Kansas City was the most fun I ever had,” he says. Two years later, he returned to New York to gain supervisory experience as an assistant metropolitan editor, accomplishing that transition, Ryan says, “gracefully and successfully.”

In the fall of 2013, another opportunity presented itself, and it would end up changing both his trajectory and the newspaper’s.

Again, the catalyst was Abramson, who in 2011 became the first female executive editor in the paper’s history. Mark Thompson, the Times’s CEO, “made it clear that he wanted the newsroom to think of new paid products that would bring in extra revenue,” says Abramson, and she asked Sulzberger to head the committee charged with that task. The assignment was a natural step in Sulzberger’s grooming process, she says, but “he had his terms.” He wanted to pick his team (he had “exquisite taste,” she says) and free its members from other work.

Several weeks later, he asked “to switch the mission away from [new] products to focus on the core” of the organization, and, again, Abramson said yes. “But I don’t think I recognized that it was also opening a bit of a Pandora’s box,” she says. “I didn’t think it was going to be a report card on how we were doing digitally.”

In March 2014, Sulzberger stunned Abramson and others by delivering a searing indictment of the company’s lack of digital progress. “There was a boldness to that and a real urgent energy that ended up sparking real change,” says Ryan.

Jon Galinsky, now the newsroom strategy manager, worked closely with Sulzberger on what came to be known as the “innovation report.” Galinsky recalls: “There were a lot of debates at that time within the innovation team. We went through many, many drafts, and A.G. spent a lot of really long nights typing stuff up and having us tear it apart, and going back to the drawing board and starting over again. The way that he led that team was a really collaborative process, where everyone had something to contribute.”

Sounding what Galinsky calls “an alarm bell,” the report declared: “The New York Times is winning at journalism…. At the same time, we are falling behind in a second critical area: the art and science of getting our journalism to readers.” It called for more news-business collaboration in product development, more emphasis on social media promotion, and more digital creativity.

Abramson laments that the report didn’t credit her accomplishment in merging print and digital operations. Her recent book, Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts, calls it “an epic defeat,” even a betrayal. In mid-May 2014, she was fired by Sulzberger’s father—not, it seems, for digital failures, but because of what the Times called “management issues” that had eroded her ability to run the paper. (Abramson has suggested that conflict over her compensation and other disputes also played a role.) Managing editor Dean Baquet, an Abramson ally turned critic, succeeded her, becoming the Times’s first African American executive editor.

Galinsky says the innovation report was “a big inflection point for the institution.” But it was also critical for Sulzberger himself.

It demonstrated, he says, “that without meaningful change, the future of this place that I believe plays an essential role in society was in real question. And once I realized that, and once I realized that the leadership of the company and the newsroom needed help fixing this, the notion that I would spend my time writing articles started to feel indulgent.” He was, he says, “uniquely placed to help solve some of the problems I had identified”—an acceptance, finally, of the destiny he had regarded with so much ambivalence.

Sulzberger says Abramson had asked him to prepare only eight print copies of the report. But the day after her firing, a version leaked to BuzzFeed, one of the Times’s digital competitors, and was posted online.

“We had an emergency innovation committee meeting after the report leaked, where we all just got in a room, including A.G., and said, ‘Holy shit, are we all going to get fired?’ ” Galinsky recalls. “The Times was a different place at that point. We didn’t honestly air criticism about ourselves.” But the panic subsided, and Galinsky says: “It’s good that it leaked in the end. It made us accountable to do the things that were in there.”

“Is this OK to steal?”

It is 1:30 p.m. on a cool April day, and the publisher has just emerged from a Q&A with the company’s product and design team. Perched on a chair, in his informal uniform of a sky-blue shirt, dark grey sweater and blue jeans, he has spent an hour cultivating good will, explaining company strategy, and even earning a laugh or two. Outside the meeting, he encounters an enticing buffet. In the rush of the day, he hasn’t yet had time to eat his takeout sushi lunch. So the man whose family controls the company asks a passing employee for permission to purloin a cookie.

Permission is, rather unsurprisingly, granted.

“That kind of encapsulates his personality and his approach to the job in a nutshell. He doesn’t hold himself above other people,” says Galinsky. “In all the roles that he’s had here, despite being who he is, he just comports himself like any other member of the staff.”

Everyone who discusses Sulzberger notes his lack of ostentation. So intense is his desire for privacy that he declined to have his recent wedding announced in the paper of record. That he was the one to jumpstart digital transformation at the Times entails more than a little irony: Schooled in print, he had virtually no social media presence. He never joined Facebook and tweeted exactly twice before giving up on Twitter. (The day of the April interview, he was finishing a piece for the Times’s just-launched Privacy Project, examining the tradeoffs of the digital age.)

But, after holding Q&As around the newspaper to explain the innovation report, Sulzberger accepted the opportunity to fulfill one of its recommendations by heading a newly created newsroom strategy team. By then, what he calls “the process”—the competition with Dolnick, who had been named senior editor for mobile, and Perpich, a Harvard M.B.A. who had joined the company in 2010 to help design the paywall—was underway.

“We joked that we feel very lucky,” says Perpich, a first cousin who spent childhood Christmases and family vacations with Sulzberger and used to catch frogs with him in their grandfather’s pond and swimming pool. “We all have similar values, but very different skill sets. So we knew, however this shook out, there was a role for each of us to play.”

In October 2016, a seven-person selection committee (composed of family members, senior managers, and independent board members) named Sulzberger deputy publisher, marking an end to the cousins’ polite, G-rated version of Game of Thrones. By prior mutual arrangement, the three went out for drinks afterwards.

“I looked a little shell-shocked,” Sulzberger says. “My head was spinning. I’m sure their heads were spinning. They ordered a round, and then Sam turned to me and said, ‘Let’s help you plan tomorrow.’ And the first thing he said was, ‘Let’s go to the Page One meeting, and we’re going to sit on either side of you, and before you say anything, we’re going to stand up and explain why you were the better pick.’ ”

Since then, Sulzberger notes, Dolnick has created The Daily—“now America’s most downloaded podcast,” with “more listeners every day than our front page ever had readers.” On Feb. 1, The Daily aired an episode titled, “The President and the Publisher.” It braided Sulzberger’s account of his two Oval Office visits, on July 20, 2018, and Jan. 31 of this year, with audio of him telling the President directly that the phrases “fake news” and “enemy of the people” had damaged journalists and press freedom around the world. Another Dolnick project is a TV show, The Weekly, highlighting Times reporting, which premiered June 2 on FX (and whose episodes also will stream on Hulu).

Sulzberger credits Perpich as “the principal architect of huge swaths of the company’s strategy”—the move from an advertising-dependent to “subscription-first” model, “a really profound and important moment in the history of the place.” In addition to the paywall, Perpich developed the subscription-based Cooking and Crossword apps, which Sulzberger says “show that we’re not just for news—we are for a wide range of purposes to help people live their best lives.”

Sulzberger’s own role is evolving, too. The New York Times publisher used to spend considerable time navigating the divide between the news and business sides of the company, making sure company goals were in sync. While some separation remains in place to guard against conflicts of interest, Sulzberger says, increased coordination, particularly in product development, has become the rule.

“What I think has grown more substantial … is the need to have someone who’s really taking a long view of this institution,” he tells the product and design team. He cites his father’s decision “to preserve our investment in newsroom and to increase our investment in product, technology, and design in a period in which we were rapidly slashing our overall budget and facing real financial peril.” It was a long bet, he says, that is paying off. “So I think of myself as a voice for the longterm, and as someone who spends a lot of time thinking about our long-term assets: our brand, trust of readers, how people engage with us, and our culture.”

Increasing diversity—of both employees and readers—is one priority, Sulzberger says. But his greatest worry, he says, is “the decline of trust in journalism, and particularly the polarization of trust,” with Republicans far less likely than Democrats to have faith in the media.

“That is really troubling for an institution that prides itself on its independence—that believes it was put on the face of the earth to follow the truth wherever it leads and to report without fear or favor. Think about those phrases that circle around this building,” he says, “and think about the public perception right now.

“A majority of Republicans now say that the news media is the enemy of the people. They’d rather get their news directly from the president. And a majority say they believe the government should be allowed to shut down organizations that report ‘fake news,’ which is in the eye of the beholder. That’s so troubling not just for this institution, and not just for the industry of journalism,” Sulzberger says, “but for the society we live in.”

Julia M. Klein, a former staff writer for the Philadelphia Inquirer and contributing editor at Columbia Journalism Review, has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Mother Jones, the Nation, and other publications. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.