Your editor and publisher (probably not a great combination of functions) recently wrote about how Brown has run into objections from students over various offensive opinions published in the BDH, BAM, and elsewhere. I found, within that, her short section about freedom of speech and hate speech interesting in its assumption. Is the question really, “Are you for or against hate speech?” A similar question might be, “When did you stop beating your wife?”

There is no widely accepted definition of hate speech, although most states have their own for legal purposes. But we all know it in its extreme forms, and hopefully disapprove. We also need to acknowledge that it attracts a form of censorship, just as the Brown students Ms. Jack described have successfully demonstrated by rebelling against people, papers and articles that offended some of them. Should one group’s sensibilities be the arbiter of free speech? It is not the obvious, but the gray area, as always, that is the problem. That area is where more and more people will disagree, if given the opportunity. But when free speech is abridged by the actions of a relative few, and supported by the institution, I wonder whether those actions, in the abstract, are any less dangerous by extension than outright censorship by media, government, or anyone else.

It seems to me it is the duty of the leadership of Brown and the BAM to make sure that the student body understands that what makes free speech valuable is to be able to hear it. Hate speech which incites violence, and maybe a few other criteria, has to be muffled. I get it. That stuff falls in the legal category of a “threat” to my mind. But does Brown only stifle opinions when a small, transient, part of its 18-22 year-old student body gets upset? That just prolongs the ability to get to the root of things we don’t like, which is akin to sticking your head in the sand. Brown students may be graduating into the real world with unrealistic expectations about this subject and an inability to deal with people who have different gray area opinions. Brown should set itself above all that by training students to allow, listen carefully, and even dissent, but not to demand censorship and removal from the University of such things. You never know what that might produce. Who is in charge of the asylum, anyway?

—Brian Barbata ’67

Kailua, Hawaii

None of the following is an apology for anything. It is what I know from history books and experience with 44 presidential administrations -- half Democrat and half Republican -- several wars, and lots of changes. Please do not expect omniscience!

In medieval Europe, most people were slaves. They were sometimes called peasants, but that term included the farmers working small plots not part of a baronage. There were rules. A baron had to house, clothe, feed, provide courts for, allow 111 holidays for (Sundays, 7 high holy days, 12 days of Christmas, and 40 days of Easter), provide medical care for, bury, and give spending allowances to their peasants. These rules were enforced by the Roman Catholic Church, which explains the holidays. These slaves were mostly of the same human variety and culture as their barons. Most barons provided clothing identifying them with the baronage. Some barons put metal bands around their peasants’ necks or arms. Peasants did not fight in wars which were fought by the upper class. Pretty much, if his baron was a good manager, a sound businessman, a competent warrior, compassionate, and intelligent, a peasant lived decently and was happy. If his baron was a lazy, selfish, craven fool, a peasant was in deep kimshi. His baronage might even be overrun and he and his fellow peasants summarily executed so other peasants could take their places.

In Biblical times, there was a whole spectrum of slavery. The majority of slaves sold themselves into slavery to pay debts. Pretty much, they selected which owners they would accept. (In Israel, the Mosaic law required such a slave to be set free after a set number of years or in the year of Jubilee if the slave were a fellow Israelian unless the slave preferred to remain with his master.) The bottom feeders of the ancient world’s economy were hirelings whose own the sheep are not. A hireling was not good enough to be accepted as a slave. He was hired for a few days of work during harvests. He was naked, always a male, slept in the streets, never allowed a wife, and shoveled into the garbage dump when he died. Then there were slaves of the state. These were people who had violated some nation or empire’s laws or were prisoners of war. They worked in labor gangs without creature comforts or medical care and were left to rot in a garbage dump when they died. The Africans sold to American slave traders were largely prisoners of war captured in tribal wars. If a hostile village was captured, the people were sold as slaves or exterminated in order to get arable land in a time of increasing famine. Had they not been sold to Americans, these POWs would have been killed or put in work gangs and worked until they died. America was an ocean away. Transport across that ocean killed many of the POWs before they could become slaves. In America, there was no ruling church. Law was a patchwork of colonies with different geography and different ethnic populations. Millions of people were involved. The labor was needed to tame a virgin wilderness under lawless conditions. Almost any tale you might tell from the most horrific to the nicest would be true.

After the wilderness had been cleared, it was not cost effective to own huge numbers of slaves, but the slaves were THERE—live, breathing humans of all ages. Industrialists in the northeast were starting big enterprises and needed labor, but they were not willing to feed, house, and clothe slaves. They offered a wage and it was up to the employee to take care of himself. And they were certainly not going to pay employees for 111 off-days. No work—no pay. That would have been enough of a problem, but most American slaves did not understand Western language, technology, or culture. Worse yet, those who remembered African culture and language were from hostile tribes and the others had no culture at all. These people were leaderless and dependent. There were a lot of them. Some portion of them were actively hostile to the European-descent population. The Scotch-Irish population, having been brought from Irish prisons to be slaves, had revolted and hidden in the mountains. They had expected that the Africans bought to replace them would revolt and were furious that that had not happened. They felt the Africans had sided with the baron wannabes and hated the Africans. The leaders of the agricultural south and the industrializing north hated each other and were not going to cooperate to retrain farm workers for industrial jobs. Finally, the slaves were all of a different human variety and looked strange, even frightening, to the rest of the population. Furthermore, the reverse was also true.

The ingredients for mass violence/ tragedy were abundant. We are all lucky it was not any worse than it was and not any worse than it is now. We fought a war that killed a tenth of our population and decided two things. The Northeastern industrial complex was in charge. Slavery was not a legal means of organizing labor. Ergo, the labor riots of the 1920s to impose feudal law upon employers that resulted in the 52 Saturdays and 5 secular days replacing the 11 days of Christmas, 40 days of Easter, and 6 of the 7 high holy days that we had lost, along with requiring employers to provide a living wage. We are adding health care, but no one has yet broached burial costs.

Democrats are currently offering the feudal package plus education, sans burial costs. (Maybe they could add inauguration day to make it 111 off-days?) Instead of a bunch of barons or employers, we will get ONE payer -- Uncle Sam -- so we will get uniform treatment. Do we want everyone to get the same education or the same health care by the same standards, which are set by federal bureaucrats working for whomever we elect as president? You may want to outlaw the teaching of the Bible, but suppose the president and his crop of bureaucrats is in favor of teaching the Bible? Or vice versa? Ditto for health care policies. Do you want alternatives to be available?

Our employers have discovered a way to avoid the current labor laws—hire people who must accept a nonliving wage and abusive working conditions or else be deported as illegal immigrants. It began with agriculture but has spread to construction. What use are minimum wage laws if an employer can fetch underpaid labor from across the border? We argue over the wall or minimum wage. Doesn’t anyone want to enforce the current labor laws on employers? Should not the debate in the BAM be about what is being proposed/ done now, not the stuff that we cannot change that has already happened and what each of us believes or refuses to believe about it? WE are the new baron wannabes, slave traders, industrialists, prisoners of war awaiting enslavement, Scotch-Irish languishing in prisons, various and sundry small farmers trying to make a living, whomever. We have different issues and circumstances from our ancestors, but the same choice.

Stick with our personal anger, envy, attitude, fear, greed, and resentment OR cooperate with others and improve everyone’s lot. One by one, each of us will decide. I am old and will not be forced to live with the results, but younger folks will.

—JW Lane ’71 PhD

Tallahassee, Fla.

One of the best consultants I have worked for remarked to me “The primary human motivators are fear and greed.” This thought was the integration of decades of successful sales of high-level consulting contracts to captains of industry. He did not say these were the only motivators. He did not endorse the result. He only spoke of the conclusion.

I have read and reread the letter from Brian Barbata and all the comments several times. The only model which explains this firestorm of a result is Mr. Barbata used a series of trigger words which shut down any principled reaction to his underlying premises. However, “Get over it” was a bit over the top.

Let me disclose my bias. I believe in the integrity of our existing Constitution, especially the First Amendment. I don’t think anyone is served by suppressed speech. Those who have not read it, or do not remember it, should read Brandeis’s concurring opinion in Whitney v. California. It is the gold standard of First Amendment law, if not good practice. Emotional toll caused by speech does not override the First Amendment, because those hurt by speech can walk away from it. Not every preposterous idea has to be eviscerated. I would like to thank Meghan Koushik for mentioning the Overton window. I am not a policy wonk. I had never heard of the Overton window, but for the subsequent couple of days, I read everything I could, indiscriminately, about the meaning and consequence of the Overton window. One thing I concluded; the bounds of the Overton window are set only by consensus. No interested party to a discussion gets to unilaterally set the bounds around what is fit for discussion. A person can choose not to participate, but cannot exclude others from participation. To exclude results in complete polarization, a modern-day Tower of Babel. A concrete example of this is no one party gets to label disagreeable speech as hate speech simply to move it out of the Overton window and, thereby, silence it.

At the core, Mr. Barbata raised two substantive points. First, Brown would not exist without slave trading wealth. This is debatable. Second, at different epochs of our collective history, some form of slavery was an economic imperative to some actors. This is also debatable. I could read into his letter, no explicit or implicit endorsement, no slavery apology, and certainly no moral acceptance of his conclusion. I question why others read it differently. Certainly word enhancement, reading between the lines, the failure to note time context, projection, presumption, opinion, labeling, supposition, name calling, retreating to the echo chamber of like opinions, do not change the words.

I have trusted Hegel’s dialectics most of my life. The inevitable conclusion is, without an antithesis, there is no synthesis, and synthesis is thought to be a morally higher premise.

It is said that the people with the greatest ability talk about ideas, concepts, and principles, those with lesser ability speak of current events, and those with the least ability talk about people. Take the high road. Brown gave you the tools to go there. The idea of what is or is not permitted for discussion is powerful. Inherent in its power is the possibility to weaponize this idea to do more social harm than good. To borrow a partial phrase from your editor, never before in our limited memory have we needed to “bring(...) to light issues that need to be confronted and interrogated,” the issues of this letter to the editor exchange, and many, many, more.

—Don Michelinie ’70

Andover, Mass.

In reference to the Letter from the Editor in the November/December issue; From my experience of working with another country (Haiti) for more than two decades and living there for more than half of that time, I have come to see even the term indigenous as problematic. I prefer the stark realism of the Canadian term First Nation. Why? Because First Nation emphasizes a very important point: we are all migrants. The importance of this point is self-evident, isn’t it?

For over 20 years, I have been called fondly, disparagingly and neutrally blan (Kreyol for foreigner). The fact that this coincidentally called attention to my skin color was second to the fact it addresses the advantage I have of being able to come and go from the island easily. Still, I asked students not use the word at our school (Louverture Cleary School, Croix des Bouquets, Haiti). I also asked that teachers not be referred to by Mr. First Name / Miss First Name. Both seemed to harken to a time of heightened racial division, slavery and the plantations found throughout America. (America here being the whole of the Western Hemisphere.)

In preaching, I have taken to reminding my fellow Catholics that we are an immigrant Church. Our namesake founder was himself a member of a fleeing, refugee family. Comically, I point out that unless you don’t have a belly-button and live in an amazing garden, you have migrated to survive, to work, to live, to thrive.

Reparations are a very difficult issue. Many Civil War and post-Civil War immigrant families, now established U.S. families, may find it hard to pay for a privilege they fell into rather than engineered. It is not clear how much, for instance, Irish immigrants have benefited from slavery. I will leave that to the economists and politicians, and the occasional Ivy League president, to determine. However, the latter may want to consider first how their lofty pay may be a result of the legacy benefits of slavery. I am certain about three things. We are all humans. We are all migrants. We are far too prone to xenophobia and war.

—Patrick Moynihan ’87

Vero Beach, Fla.

I write regarding the publication of the letter about slavery by Brian Barbata ’67 (“…slavery [in the Eighteenth century was] totally understandable and clearly necessary…. Everyone should get over it”) and responses thereto in the November/December BAM. By this time everyone should recognize that slavery is America’s original sin. It was evil. Slavery has left a stain on our country that has not been fully eradicated 150 years after abolition, and may never be completely eradicated. I fully agree with the writer who said that legacies of slavery, including mass incarceration, are alive and present in our society today. The monument on Brown’s front campus recognizes this history and acknowledges the University’s complicity in it. At the same time, it is clear that many Americans do not recognize this history, as demonstrated by Mr. Barbata’s letter. Advocating the suppression of such expression in the pages of BAM and at Brown generally will not eradicate it. It will only serve to turn Brown into an institution of hermetically-sealed thought with limited relevance to the country as a whole. I am not suggesting that direct hate speech (use of the “n” word for African-Americans or the “k” word for Jewish-Americans or the “w” word for Italian-Americans) be published. But Mr. Barbata’s letter did not sink to that level. It was an expression of racist ignorance which should be opposed with factual historical analysis, not suppression.

—Robert F. Cohen Jr. ’68

Morgantown, W. Va.

I applaud your policy of acknowledging all letters. My input: Racial discrimination is, or should be, a two-way street. But I’ve never (yet) seen an accusation that so-called minority groups discriminate against “Caucasians,” apart from the now seldom-used word “honkies.” But recurring TV displays of minority gatherings make it clear that they have no qualms about stirring the pot as much and as viciously as possible. And they have their leaders, too. I abhor discrimination, in any way, shape or manner. But it only seems fair to make the point.

—Jack Campbell ’48

Charlton, Mass.

I read with interest and appreciation your thoughtful self-evaluating editor’s note What’s Fit to Print? (Nov/Dec 2019). It’s clear the magazine is doing a lot of soul-searching and engaging in good faith. That said, this issue is far easier than you make it out to be. The entire point of a Letters to the Editor section is that it is curated to display the best and most insightful submissions. “Not ad hominem” is an absurdly low bar, and it allows letter writers to abuse BAM’s generosity for their own ends, quite possibly acting in bad faith. I support reparations, but it’s remarkably easy to construct a non-inflammatory argument against them. Watch:

“The abuses African-Americans suffered were horrific. However, the population of the U.S. who arrived after 1965 should not be unfairly financially burdened. One could provide a similar amount of assistance to descendants through a broadly redistributive tax, funding for a special unit to aggressively prosecute redlining…” etc.

I disagree with the above statement I just wrote, but that’s how someone who’s interested in a good-faith discussion makes an argument against reparations -- acknowledging harm, empathy, thinking of policy solutions. Someone who says “get over it” clearly has no interest in a thoughtful, respectful discussion and is essentially throwing a temper tantrum in print. Which is their right. As it’s your right not to print it.

Many longtime conservative commentators—Jennifer Rubin, David Frum, and campaign manager Rick Wilson—have written extensively on the GOP’s intellectual disintegration and descent into a party of utter bad faith with no policies beyond “trolling the libs.” Conservative Max Boot wrote an entire bestselling book about it, The Corrosion of Conservatism. The GOP has a history of abusing good-faith publications and bullying them so they avoid making judgment calls of any kind, and BAM has both a right and a responsibility to take that context into consideration. BAM makes judgments on what should and should not be in its magazine every issue for a wide variety of reasons. If letter writers submit deliberately inflammatory screeds, BAM is well within its rights to deny those screeds its valuable platform. Curating and exercising good judgment are not “censorship,” they’re absolute necessities for creating the kind of stimulating, thought-provoking conversation valued so highly by the Brown community and the magazine.

—Greg Machlin ’02

Los Angeles/Falmouth, Me.

I am the father of a Brown University student who is majoring in history and economics. I want to applaud the editor and publisher for their courage in continuing to support an open forum for discussion. History is an uncovering of the facts of a time and an opinion as to the origin and motivation of the characters of the time. Revisionist history is a process of altering the facts according to a preconceived notion of behavior, whether current or past; communist nations were masters of this. Our current problem is ‘labeling’, such as ‘racist’, whose purpose is to exclude opinions based on the facts; applying a label allows a person to dismiss the holder of an opinion, and it is very dangerous to society. The letter from Mr. Barbata is important, as it has provoked a healthy debate in the society that reads BAM, and it offers an opportunity for the writer of that letter to continue to be part of that society and reflect on the many different interpretations of that letter. When individuals and groups are labeled and excluded from an open society, their beliefs may flourish and grow without the necessary education that comes from participating in open discussions that in time lead to changing of views. It is essential that Universities and individuals see that shining a light on deeply held opinions is a necessary educational process for all involved, it does more harm when individuals whose opinions are not popular are excluded. Young minds are no different from old minds when they are allowed to label and exclude. No matter how much one disagrees with an opinion, every person has a right to one and an obligation to change it so as to support the society that protects that opinion.

—Prof. Mike Gross (parent)

Dalhousie University

Halifax, Novia Scotia

Canada

Since you ask: Yes, you should exercise judgment in publishing letters to the editor. After all, the editor & publisher is responsible for everything that appears between the covers of the BAM, or on its “platform” in the jargon of this century. The corollary is that once you publish something you should stand behind that decision, except in very few clearly defined circumstances such as libel, plagiarism or fraud.

Until now I had no idea the BAM’s policy was to publish all letters to the editor. Then I saw the current issue, which states: “The BAM publishes all letters to the editor. We edit out obscenities, ad hominem attacks, or known false statements of fact. We do not censor opinions. For our full policy, click on ‘Submit to the BAM’ at the bottom of our web pages.” How about this one instead? “The BAM invites letters to the editor. We ask that you treat your fellow alums with the same civility and respect that you would when talking with them face to face on campus.” Then toss out ignorant letters like the one that said all peoples throughout history have taken slaves or hateful letters like the one that said the writer looks forward to when old alums are dead. (I’m not there yet).

—J.V. Reistrup ’58

Annapolis

Thank you for your editorial “What’s Fit to Print?” Thank you for requesting input on this subject. Letters that offend me are those that take too many words to say too little. Letters that offend me are those that overgeneralize. Letters that offend me are those where people say more than they know. Hopefully we can all learn to communicate more accurately. Hopefully BAM will help people to learn the difference between opinion and fact.

—Frank Rycyk ’66

Jefferson City, Mo.

I just wanted to say that I thought your comment in the latest BAM was well written and did a nice job of posing the background and issues. I’m unfamiliar with the latest controversy, though I was an undergraduate at Brown in 2001 when the Horowitz ad-controversy arose. I would encourage the BAM to follow the Chicago Principles, which, as you may know, have become the standard for universities in dealing with issues of free expression. The Chicago Principles have been adopted by Princeton, Columbia, JHU, the Univ. of Wisconsin, Amherst, Washington Univ., and others. While an alumni magazine is obviously somewhat different from a campus, it’s hard to see how these principles wouldn’t apply. Thank you for your work.

—Josh Bernstein ’01

Hattiesburg, Miss.

The most recent copy of the Brown Alumni Magazine lays bare the idiotic interface between radicalism (which liberal parents and alums fondly encourage) and the reality ‘grownups’ actually live in. This cake is iced with marketing pages, using virtue signaling as the hook, where the lauded radicals, rejecting incremental solutions in favor of getting arrested, can dovetail with alums advertising private venture capital expertise, $285 white shirts, $240 earrings from discarded metal, $225 European sneakers, $285 Thai sneakers, a politically correct ‘butt cover’, a $790 bracelet too small to see, among other ‘let them eat cake’ items so integral to the revolution Ivy radicals have in mind. It’s a real Win-Win when marketing meets political posturing. You know you can’t pretend to be Abbie Hoffman and incarcerated wearing clothes which aren’t chicly showing your affluence, how evolved you are and flattering yourself head to toe with moral superiority. I’ll bet money AOC wears only the most expensive PC clothes that money can buy too. Bernie’s unaffordable revolution will be here any minute. So, get ready and stock up on these necessities before we all go to gray uniforms in the new Luddite Socialist utopia.

Not to be outdone, the magazine of course is a perfect platform for Brown itself to peddle their Visa cards, a monogrammed brick in the wall, overpriced exclusive trips (using unforgivable fossil fuel for transport, soon to be illegal under the Green New Deal), Executive re-Education (for jobs in unforgivable corporations who will never be carbon neutral), and ending with soliciting a piece of your IRA. It makes you downright nostalgic to go back for a reunion at the exclusive Club Brown.

Kristian Niemietz recently wrote: “Over the past hundred years, there have been more than two dozen attempts to build a socialist society. It has been tried in the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia, Albania, Poland, Vietnam, Bulgaria, Romania, Czechoslovakia, North Korea, Hungary, China, East Germany, Cuba, Tanzania, Benin, Laos, Algeria, South Yemen, Somalia, the Congo, Ethiopia, Cambodia, Mozambique, Angola, Nicaragua and Venezuela, among others. All of these attempts have ended in varying degrees of failure. How can an idea which has failed so many times, in so many different variants and so many radically different settings, still be so popular?”

—Marjorie Wright ’77

Dallas

I commend the BAM for being a champion of free speech in the Brown community. Your publication of a controversial letter on “getting over” slavery brought an onslaught of responses which were shocking in their demands for censorship. But people with unpopular views shouldn’t be cowed into remaining silent. I believe the original author was correct in suggesting we have a lot to “get over.” First, we need to end the discussion of “reparations for slavery.” The notion that a fifth generation of non-slaves should be compensated by a fifth generation of non-slave-owners is unworkable, divisive, and racist at its core. Get over it? You bet!

Second, we need to stop “erasing” history that some find offensive by contemporary standards. Let’s not diminish the fact that slavery was—and always will be—an abomination. But learning from dark historical mistakes does not require renaming buildings, shunning early American flags, or destroying artwork or statues. Get over it? You bet!

Third, we need to stop promoting campus diversity on the basis of skin color. Substituting true diversity—intellectual diversity—would seek inclusion of perspectives that challenge the “politically correct” wisdom of the day and enable the free debating of ideas. A race-blind admissions process with no “hidden quotas” is preferable to discrimination for or against any racial group. Get over it? You bet!

And lastly, we need to stop the victim-based identity politics that screams oppression at every turn, is hypersensitive to perceived “micro-aggressions,” and demands trigger warnings, grievance studies, and coddling deans. Brown students are the most privileged in history with resources and opportunities unknown to previous generations. For students stuck pondering whether a cis-gendered white male heteronormative patriarchy is standing in the way of their intersectional social justice, I respectfully suggest taking responsibility for their individual advancement through education and spending more time in the library! Get over it? You bet!

—Fred W. Clough ’76

Tiburon, Calif.

I have taken your request to heart, and attached is my statement. Thanks for opening up this very important subject to debate. I appreciate your work, and always read the magazine when it comes. I can’t say that for all of my subscriptions!

A couple of months ago I stumbled upon an author presentation on C-Span Books. The presenter was Libby Phelps, speaking about her memoir, Girl on a Wire, the story of how she, the granddaughter of the founding pastor of the infamous Westboro Baptist Church in Kansas, had “made it out” of the near-hermetically sealed environment of this fundamentalist, activist church, famous for its in-your-face confrontations with those it deems despicable. How had she managed to do this? Though she began harboring secret doubts as a teenager, her mother persuaded her to open a Twitter account and to use her teen’s voice to spread the word. What happened next riveted my attention. The predictable reactions started coming in, bifurcated into pros and cons. But mixed in with the partisans was at least one man’s attempt to establish a dialogue with her, and to gain her trust. As he did so over months, he was able to raise up for her the internal contradictions in her stands and in her interpretation of Scripture. This dialogue was pivotal in helping her to “get outside” the hermetic seal. She and her sister planned a secret escape, and she has not turned back since, though the journey has been arduous.

I was struck by the thought of a patient fellow-Tweeter taking the time to realize that behind her repugnant-to-him views was a living person, a human being, someone who could not be reduced to the positions she took on a variety of issues. I admire that person, whoever he is, and wish I could be more like him. Even though I doubt that I myself have that patience, this episode strikes me as having a singular bearing on the discussion we are having about “what views are fit to print,” to paraphrase a great newspaper. It is extremely uncomfortable to live in community; how much easier to distance ourselves, cutting off those who have views that we find repugnant, creating “communities” of like-minded people. But the trouble is, we are all in this together. Planet earth itself is an example: we will all share, in one way or another, in the future climate crises that we are being asked to face. We do not get to choose those that will go down with us, or those who may stake their future on doing whatever they can to avert catastrophe. We are still part of the human community, residents of Planet Earth. In a similar way, whether we like it or not, we are part of other communities—in this case, a nation, and a small part of that nation brought together by an affiliation with Brown University. We can choose to dismiss those whose views we find repugnant. I don’t enjoy reading those opinions myself. But the folks whose views we want to dismiss are still part of our community, and they too are human beings, not reducible to what they opine.

Maybe I don’t have the patience to get to know a letter-writer, and gain his or her trust, but Libby’s story reminds me that behind that repugnant-to-me opinion is a human being, someone who is part of this community. I need to treat that person with the respect due each human being. If I do not, I undercut the arguments I would use to support my points of view, the ones that rest on the need to treat others with dignity and respect, regardless of whether or not I like them or their views.

—Greta Schipper Reed ’60

Tallahassee, Fla.

I write to urge BAM to continue its current policy on letters. It saddens me to learn that Brown graduates seek anything less. I also abhor the sentiments and beliefs expressed in the offending letter, but I learned repeatedly at Brown the value of not restricting discourse. In English 14 (Prose NonFiction) we read and discussed Milton’s classic defense of press freedom: Areopagitica. Among its most powerful phrases: “I cannot praise a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary, but slinks out of the race, where that immortal garland is to be run for, not without dust and heat.” Despite its 17th century cultural trappings, still a useful reminder of what being educated entails. I also vividly recall the visit of George Lincoln Rockwell, Brown alum and head of the American Nazi Party, to speak in a campus lecture series, one that also hosted Norman Thomas, the nation’s prominent socialist; William Sloane Coffin, a leading anti-war figure; and Richard Hofstadter, debuting his Paranoid Style in American Politics. Rockwell’s physical appearance, manner, and rant conveyed messages about racism and hatred I could not have gotten from my history books. Hillel enhanced the experience with a simultaneous exhibit, including samples of Rockwell’s repulsive pathological work for the Brown Humor Magazine. In summary, my education prepared me for the mixed and troubled world I’ve inhabited. At a time of increased polarization, promoting open exchange is more valuable than ever.

—Judith A. McGaw ’68

Portland, Ore.

In response to your request for commentary about editorial censorship, I offer the following. While I am not a graduate of Brown, my father and other relatives, including a Pulitzer Prize winner, are alumni. The letters you printed in response to Mr. Barbata’s original commentary were filled with self-righteous intolerance and hate. It seems that those who worship at the altar of the politically correct demand their views be accepted by all, but if anyone dares offer a differing opinion, they label them racist or sexist or some other term meant to intimidate or silence them and any others who might be tempted to disagree with their views. Apparently, any speech that disagrees with their opinions is hate speech. Slavery in this country ended over 150 years ago. I suspect if those men and women who endured and survived enslavement could view the opinions of some of their descendants, they would be disappointed in them. Despite incredible government assistance and wonderful opportunities given them by institutions like Brown, some, like these letter writers, seem unable to prosper and find happiness and hope while living in freedom. They are like spoiled brats. They are convinced of the righteousness of their views and anyone who dares to disagree with them is wrong and should be silenced. This is reminiscent of Stalinist Russia. If the Brown Alumni Magazine surrenders to these writers’ extortion demands, then you become merely partisans and are no longer journalists. If Brown University caves to these extremist views and suppresses opposing opinions, then it might as well shut down. It will then no longer be an educational institution but merely an indoctrination factory.

—Robert E. Thompson

Brunswick, Me.

I have had some conversations with both alums and others on this subject, and those I talked with all agree that you should not censor the letters that you publish. If the BAM cannot publish various points of view then the magazine will just become another echo chamber for one set of opinions. As one friend pointed out, the people who write letters to the BAM are Brown alums. Surely the BAM cannot decide whose opinions it will value and publish. Also, the original letter brought about several letters with very different viewpoints, which further educated everyone who read them. That would not have happened if the original letter had never been published.

Personally, I found the original letter historically inaccurate and offensive, but I do think the writer has a right to send a letter expressing his opinions to the BAM and the right to have it published. Other alums have the right to disagree with it.

Do keep the editorial policies that you outlined in your comments. I think they are fair.

—Jane DeCourcy Wong ’62

Berkeley, Calif.

I’ve just finished reading the various responses to the much-discussed Sept./Oct. letter on Brown’s links to slavery, many of which demanded that the original opinion be ‘taken down’ or ‘immediately apologized for’ by the magazine’s editors.

As an alum, a reader, and former BAM staffer, here’s hoping that the BAM’s letters column will be allowed to hold its ground as a place for all views, even those that many strongly resent. If letters are to be censored or suppressed, then why not move on to monitoring classroom discussion or removing offending books from the Rockefeller and Hay libraries?

One constant concern for many of us of a certain age is this one: Why do so many in educational communities these days seem to see danger in the clash of ideas, instead of opportunity? Yes, opinions can be hurtful, but isn’t the college experience at least in part about analyzing them, and effectively refuting? Why not bring a bright light to bear on comments like the one from the Sept./Oct. issue and others like it? Why not welcome these into the midday glare that only a university full of educated and iconoclastic people can create? If you disagree with its points, as I happen to, defend your turf. Do it so well and so strongly that everyone will remember your views. You may feel that you can bury abhorrent ideas by depriving them of “platform.” But down in the darkness and silence bad ideas have a funny way of taking root. Those who espouse them don’t disappear. Life doesn’t work like that. And, as you may have realized by now, by trying to squelch opinions you award them far more currency than by fair-minded exchange.

—Peter Mandel ’81 AM

Providence

I applaud the writers of letters objecting to dismissive views on the legacy of slavery expressed in the “get over it” letter in the September/October BAM. However, I decry the calls for censorship. The hallmark of a university is the free and open exchange of ideas. The expression of repugnant ideas elicits a response in opposition––as it did in this case––providing an opportunity to champion and present an alternative view.

Although students of my era at Brown did not have the advantage of the diversity on campus today, we were not unexposed to differing outlooks. Both George Lincoln Rockwell and Malcolm X spoke at Brown.

As to the writer who looks forward to the death of me and my classmates, I ask, wouldn’t that sentiment expressed toward any other minority group be labeled hate speech?

—Jonathan Robbins ’62

Whitefield, Me.

I am a proud black, female graduate of Brown ’78 and was equally proud to participate in the takeover of University Hall during that period. I am writing to BAM for the first time in 40 years to support your decision to print Mr. Barbata’s letter. While I vehemently disagree with his opinion that we should just “get over” (slavery), the First and Second Amendments to our Constitution exist so that our democratic republic can be exposed to a variety of opinions, debate them, and—in the case of the Barbata letter—expose the complete lack of support for his beliefs within the Brown community. Ever true,

—Colette Wallace McEachin ’78

Richmond, Va.

Which letters are fit to print?

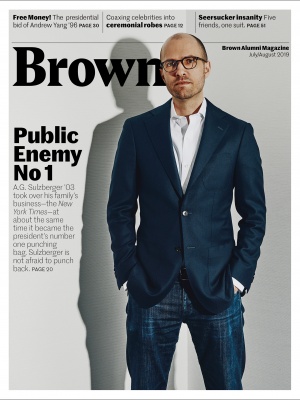

Last issue, we asked for feedback on BAM’s policy of not censoring opinion in letters, after some readers objected to our printing one saying people should “get over” slavery. We got more thoughtful responses than can possibly fit in this section; we hope you’ll read them online, linked to the story “Northern Aggression.” A sampling: Colette Wallace McEachin ’78 wrote, “The first and second amendments exist so that our democratic republic can be exposed to a variety of opinions, debate them, and—in the case of the Barbata letter—expose a complete lack of support.” Josh Bernstein ’01 referenced the Chicago Principles. Peter Mandel ’81 AM asked: “If letters are to be censored, why not monitor classroom discussion or remove offending books?” Judith McGaw ’68 recalled seeing the head of the American Nazi Party—a Brown alum—speak on campus: “My education prepared me for the mixed and troubled world I’ve inhabited.” But J. V. Reistrup ’58 said letter writers must “treat fellow alums with the same civility [as] talking face to face” and BAM should “toss out ignorant letters like [Barbata’s] or hateful ones like the one that said the writer looks forward to when old alums are dead. (I’m not there yet.)” Greg Machlin ’02 concurred: “Exercising good judgment is not censorship,” he wrote, especially when tone indicates a writer is “trolling.” Some wrote of learning from others’ letters, others railed against what they saw as intolerance. We’ll return to this subject, but for now, we’ll leave you with Greta Shipper Reed ’60, who told of two people, far apart ideologically, who nonetheless began an online dialogue that rescued a teen girl from Westboro Baptist Church: “It is extremely uncomfortable to live in community. How much easier to cut off those who have views we find repugnant.... But we are all in this together.”

—Pippa Jack

Editor and Publisher

Brown Alumni Magazine

To Our Readers:

I am writing as Editor and Publisher of the BAM. While we typically don’t publish letters online between print issues, we felt it was important in this case to provide a forum for the many voices we’re hearing that take issue with two letters in the September/October issue of Brown Alumni Magazine. Both letters responded to our article “Northern Aggression.” We will be posting responses as we receive them.

The magazine for its 119-year history has been editorially independent of the University, and I want to express unequivocally that the views expressed in the letters submitted to the Brown Alumni Magazine are not those of the magazine’s editorial staff. I very much regret that no note about the letters policy appeared on the page with the letters, because we never would want our alumni community to feel that the BAM’s decision to post letters represents a position about the content in those letters.

For many decades, the BAM’s editorial policy has been to allow the letters pages to serve as an open forum for readers’ opinions. We strive to publish every letter we get that directly relates to content in the magazine, as long as it is from a member of Brown’s alumni community, because the letters pages are the only place in the magazine where alumni can directly represent their own opinions, unfiltered by BAM’s editorial decision making. The BAM has long been attentive to issues of social justice. And while we do not always agree with the opinions expressed in reader’s letters—and sometimes receive letters that contain opinions we find objectionable, on issues ranging from diversity in admissions, to LGBTQ rights, to race—it has been a longstanding commitment to our readers not to suppress them. The section has a deep history of existing to bring these opinions to light for the whole community, and providing an ongoing forum for direct and vital conversations around them. The full letters policy is here.

While we may find it surprising and disappointing that views many find objectionable exist within the alumni community, we believe the community as a whole is best served when such viewpoints are not kept safely hidden, but rather brought into an open space where alumni may debate, interrogate, and assert what the community values.

—Pippa Jack

Editor and Publisher

Brown Alumni Magazine

Was the “Get Over It” letter genuine? I thought you might be trying to generate letters to the editor or start an ironic T-shirt campaign.

The writer acknowledges that cultures change with regard to owning slaves, but then clearly holds onto his own culture of the 1940’s and 50’s: blacks should be happy they’re free (and presumably, male WASP supremacy is good and natural, women can be happy supporting mWASPs, and, presumably other minorities should be happy to live in this great country).

Holding onto one’s culture is natural. We all love change…for others. I have no idea how you get someone to change some of their fundamental beliefs. If someone lacks empathy (and usually imagination as well) then they’re unable to walk in the shoes of another.

As a mWASP growing up near Washington DC in the 40’s and 50’s, with segregated water fountains I didn’t even know there was a problem. But gradually I learned that MY world is not THE world but A world. I still feel immensely fortunate to have had so many advantages. I’ve also learned how civil war affects countries for so long after the war is officially over. And I can see that the USofA is currently renewing its vows to institutional racism at the national level.

As for Mr. Barbata, I can only imagine how appropriate it would be if he were transformed into a black man unable to communicate his sudden knowledge to the white supremicists that controlled his life and the national view of what is right and just and what one should just accept and get over.

—Paul Knutson ‘65

London, UK

I am baffled and dismayed by BAM’s decision to publish a letter to the editor in the September/October 2019 issue, penned by one Brian Barbata ’67, in which he provides a defense for slavery, not just as it existed for several hundred years in the United States, but also, seemingly, for all past instances in which enslaved people were killed in the process of creating empire and capital. Certainly, BAM’s editorial staff is entitled to publish the content it feels is reflective of alumni viewpoints, but that does not mean that you are able to escape criticism for your choices. There is absolutely no defensible support of slavery; the devil needs no advocate. Brian Barbata’s comments indicate that his Brown education was woefully inadequate at instilling basic understanding, empathy, and judgment.

Would BAM’s editors choose to publish a letter from, say, a Holocaust denier? A men's rights activist? I am fairly certain the answer is no, but please, go ahead and disappoint me again. I’m sure you’ve gotten an outsize number of clicks and a good deal of engagement from publishing Barbata’s letter, but I hope you understand that the overall impressions and sentiment are not positive. What that letter demonstrated was violence, selfishness, and utter ignorance. These are not the Brown values I learned during my undergraduate career, and given Brown’s legacy of being built by enslaved people, publishing this letter was truly a tone-deaf decision.

I am requesting that BAM issue an apology (a real apology for publishing this disgusting vitriol, not a “we apologize that you all were offended” statement of passive aggression) and engage in an examination of how its own staff engage with issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion. “Diversity of opinion” is a concept that needs to be retired, as it seems to only provide cover for people who wish to spew hateful rhetoric under the guise of free speech.

—Natasha Go '10

New York, N.Y.

I was saddened to read the recently published and racist letter to the editor penned by Brian Barbata ‘67, written in response to the article “Northern Aggression.” In his letter, Barbata describes slavery as a “totally understandable and clearly necessary” institution that “everyone should just get over.”

I am even more disappointed that in choosing to publish what amounts to ignorant and hateful rhetoric, BAM defended this decision by stating our Brown community is “best served when such viewpoints are not kept safely hidden, but rather brought into an open space where alumni may debate, interrogate, and assert what the community values.” This myopic view begs the question, who exactly is served by this erroneous “good people on both sides” argument? When someone presents an opinion that is not based in fact but in racist ideology, what is the discourse that needs to happen and deserves a platform? Will BAM next be publishing letters that deny the occurrence of the Holocaust, that claim that the massacre at Sandy Hook was a hoax, that support conspiracy theories about 911? We all know that the BAM would never dare give a platform to such vitriol yet the BAM editorial staff wants us to believe that there is an actual discussion to be had about whether slavery was a justifiable evil.

I support calls for BAM to issue a public apology and reevaluate their editorial policy.

Honoring our alma mater requires that we be willing to critique it in love and stand up to it in truth. I do agree with Barbata when he says “if the Brown family had turned their backs on anything to do with slavery, the University would not exist” but that is not a laudable outcome. Brown has long acknowledged the history of the University built by slaves who were by definition denied their humanity. BAM owes our community at large the respect of honoring a legacy of suffering by not further traumatizing the descendants of those without whom it would not exist.

—Michele Benoit-Wilson '95, '99 PLME

Raleigh, NC

I am a Brown alum from the class of 2013, currently living in Brooklyn NY. I am a proud graduate of both the Africana Studies and International Relations programs. During all four years, I worked tirelessly to promote social justice through the Brown Center for Students of Color (then TWC), the LGBTQ Center, the Sarah Doyle Women's Center and the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice. Brown is the reason why I have dedicated myself to being a social justice educator now for youth and adults alike.

Those are among the reasons why I unequivocally condemn the recently published and racist BAM letters to the editor, written in response to the article “Northern Aggression,” that defend and excuse slavery as a “totally understandable and clearly necessary” institution. It's 2019. We should not and can not be giving a platform to slavery apologists. We can not “get over it” because the impact and legacies of slavery are alive and present today i.e. mass incarceration, among many others. We should not be focusing on “creating interhuman harmony” (whatever that is) as "a much more productive goal than fighting racism”.

This violent rhetoric directly and negatively impacts the descendants of enslaved people and Black students, alumni, faculty, staff and families as a whole. It can contribute to feelings that we/they and people who look like us/them don't belong on campus, and that topics related to our history and current state of affairs don't matter. This also impacts non-Black students, alumni, faculty, staff and families as you are reinforcing a clear Trumpian message that slavery is okay, necessary, we should stop talking about it and Brown shouldn't do anything to be accountable for directly benefiting from it.

In response to your Editors Note: your policy states that “The BAM does not print ad hominem attacks on individuals or groups, and does not print letters containing obscenities or what would be deemed vulgarity by journalistic standards.” What is your journalistic standard around giving space to people who excuse the theft, rape, enslavement and mass murder of a people? Why is that not an attack in your eyes on the descendants of enslaved people and Black folks as a whole? By continuing to have those letters online you are doing active harm to the Brown Community and anyone else who reads it. You cannot say that BAM is “attentive to social justice” because you allow people to debate others’ humanity. My humanity is not up for debate.

Therefore, I am demanding the following:

- the immediate removal of the attached letters from the online BAM site

- a public apology from BAM and Brown University, published in BAM and on Brown's website

- additional checkpoints into the editorial and publishing process of BAM

- continual and intersectional social justice training for all BAM staff and for all Brown employees

Hateful rhetoric, that directly inflames racism and justifies villainous institutions such as slavery, should have no place at Brown under the guise of promoting a “diversity of opinion”.

Hate speech is not an opinion. It’s hate.

—Sharina Gordon '13

Brooklyn, N.Y.

How are Black readers in the community served by providing a platform for a blatantly racist and ahistorical letter calling for Black people and Brown University to "get over" slavery? This is a viewpoint we have to hear all the time. This is a viewpoint we know exists within the "alumni community." Publishing such racism on the basis of free speech and debate is actively irresponsible and does not show attentiveness to issues of social justice. I do not know the exact number of my ancestors who were enslaved; I only have the names of a couple of them. The traumas they faced continue to affect the mental health of me and my family members. The wealth they created has continued to aide the wealthy and white generations later. The violence they endured continues to exist in the Prison Industrial Complex, police brutality, and systemic poverty and segregation.

Brian Barbata's ahistorical and racist letter has wasted much of my time and emotional energy. Not all of our country's founders were slavers. There were people who in fact weren't "foolish" but were morally wise who opposed slavery in the 18th century. The slavery used to "build the pyramids" is not an accurate comparison for the enslavement of generations of stolen Black people. Making these corrections to Barbata's atrocious letter is a waste of my time. I should not have had to see these words in the pages of the BAM.

The BAM must change their letter writing guidelines, redact Barbata's letter, and issue an apology if they truly care about being "attentive to issues of social justice." There is no reason for the Black alumni to have to endure reading the opinions of slavery apologists, just as there is no reason for Jewish alumni to have to endure reading the opinions of holocaust deniers or apologists. Giving voice to racists and bigots in the name of "diverisity" is not only a waste of paper and ink, but it is also actually harmful to the victims of the racism and bigotry. I am not "served" by reading racist delusions. In fact, no one in "our community" is.

—Sydney Island 2015.5

Brooklyn, NY

I am appalled and disgusted you would publish a letter calling slavery "justifiable" and that "everyone should get over it". That is a disgusting and horrifyingly insulting letter and you need to immediately 1) fire whoever made the decision to run it, 2) apologize to the community, and 3) redact it. I'm looking at your [letters policy] and it's pretty unheard of to have essentially no filter. There is certainly a way to promote diversity of thought—but the floor absolutely needs to be set above those advocating for the necessity of slavery. It feels pretty insane to have to write that.

I'd also argue that calling the historic enslavement of black people "totally understandable and clearly necessary" is an "ad hominem attack" on your black and brown readers.

—John Qua '13

Washington, DC

I’m a Brown alum, class of 2013. I credit Brown with being the place that first inspired me to seek a long-term career in social justice work. That's why I was particularly horrified to see the BAM publish Mr. Barbata’s incredibly offensive letter in response to the piece, Northern Aggression. Many of my classmates–particularly Sharina Gordon–have articulated with great clarity and elegance why publishing this particular letter was so ridiculous, but I'd like to add one thing based on the editor’s note that was posted. BAM states that it’s a “longstanding commitment” to the alumni community not to suppress letters that contain objectionable content, as long as they are related to content published by BAM. I encourage you to rethink a blanket policy of publishing all letters you receive, regardless of content, merely because they're written by alums. I’m all for publishing letters with controversial views or those that are contrary to the bulk of alumni opinion–when they actually advance productive dialogue. I’m a lawyer by training, so I take seriously the idea that open dialogue between different views is important. That being said, particularly in our present-day climate, I think frequently about the Overton window–as a law school friend once explained to me, this is the idea that there is a spectrum of discourse and ideas that we generally consider normative, and we’re relatively willing to move around in that window (and indeed, moving within that window is a healthy, necessary part of productive dialogue). That window has shifted right dramatically over the last few years on a host of issues from immigration to climate change, and as a result, we are increasingly forced to normalize and give weight to ideas that honestly should be considered abhorrent fringe positions. A letter that tells people to “just get over” slavery, and moreover calls it “totally understandable and clearly necessary,” does not add any ideas of value or merit to the discussion. The only thing publication of this letter accomplishes is shifting the Overton window further to the right, normalizing these truly abhorrent views, and forcing alums of color to expend more valuable time and energy pushing back on opinions that truly should not even be entertained as mainstream discourse. I encourage you to consider the enormous emotional toll, moreover, that mounting such pushback places on Brown alums of color–particularly African-American students–to start from a position of negotiating their own humanity and the worth of their ancestors’ lives in pushing back on this offensive drivel.

Every Brown alum, of course, has a right to their opinions, reprehensible as they might be. However, every Brown alum is not entitled to a platform–particularly one sanctioned by their alma mater–to share those opinions. Discourse and dialogue can be wonderful things, but only when both sides have valuable things to say.

I am deeply disappointed in BAM’s decision to run this letter, and further disappointed that its editorial staff makes the tired old defense of free speech to justify its publication decision (while citing BAM’s commitment to social justice, no less). Please rethink your policy.

—Meghan Koushik ’13

New York, N.Y.

I am writing to express extreme concern about the decision to publish letters that read as an excuse of and justification for slavery. These letters, written in response to the article “Northern Aggression”, defend and excuse slavery as a “totally understandable and clearly necessary” institution and implore people to “get over it”. These letters were just brought to my attention, as well as the response provided by Editor Pippa Jack above. I take great issue that this letter still suggests that the historical framing of slavery is an issue to “debate” and that it is the role of BAM to create a platform to “interrogate” this type of viewpoint.

Normalizing slavery—and justifying the violence, terror, and theft of life and labor that made the institution of slavery possible—is abhorrent. It is completely unacceptable to give this rhetoric a platform. We know that this rhetoric is not only ahistorical, but is reliant on a theoretical argument that dehumanizes people and justifies violent suppression. To include that statement sends a message that Brown does not care about its own culpability in the slave trade. It trivializes calls for reparative justice. Including this as a “letter” sends the message that we, as an alumni community, are ok with seeing this type of hateful speech as a thing to engage with, rather than condemning it outright.

I call into question the following statement from the editor: “we believe the community as a whole is best served when such viewpoints are not kept safely hidden, but rather brought into an open space where alumni may debate, interrogate, and assert what the community values”.

Safety for who?

While I understand the intent is to call out that viewpoints like this exist, rather than ignore their presence, at what cost does this unhiding come? And whose cost? Could the editorial staff not respond with a letter condemning this type of rhetoric? Could there not have been a different way to engage that would have instead prioritized the experiences of descendants of enslaved people, rather than sending a message that these views are acceptable? There were ways to interrogate hateful speech without giving it a formal platform, and the adherence to “debate” rather than standing with Black community members or taking accountability is a disturbing pattern of the University.

I join other alumni in demanding the following:

- the immediate removal of the attached letters from the online BAM site

- a public apology from BAM and Brown University, published in BAM and on Brown's website

- additional checkpoints into the editorial and publishing process of BAM and a review of the letters process

- continual and intersectional social justice training for all BAM staff and for all Brown employees

—Katie Parker ’14

Washington, DC

It seems that the “letters” page has become a lightning rod for a particular era of Brown alumni. This era can reminisce on a time when Brown didn’t have to worry about women, low-income students, or pesky mobilized minorities. This same era of alumni seems to be sensitive to Brown’s legacy of slavery, and its attempts to hold itself accountable. This frustration perplexes me. Perhaps they feel pressured to grapple with how they might benefit from the exploitation of others. Perhaps they wished they could use slave labor to keep their bankrupt coffee businesses afloat. Perhaps they struggle to process that they left Brown as callous conservatives and somehow ended up on the wrong side of history.

Regardless of this era’s rationale, the BAM has better sense than to publish slavery apologism. Even if the letters do not represent the views of the editorial staff, they do represent the views that staff is willing to platform. I find it hard to believe that the BAM would find room on its pages for a letter telling people to “get over” 9/11, the 2015 Paris attacks, or the Holocaust. Hiding behind the platitudes of “debate,” “diversity,” and “free-exchange” exhibits the intellectual cowardice I’ve grown to expect from many of Brown’s institutions.

Sometimes I worry about this particular era of outspoken Brown alumni. But then I look at their graduation years, and I take peace in knowing that I’ll see their names printed again soon. Was that joke too morbid? Oh well. Get over it.

—Lucas Johnson ’15

Brooklyn, N.Y.

I demand to know why you saw it fit to publish Brian Barbata’s letter to the editor that said “slavery is totally understandable and clearly necessary”. Do you have any idea how harmful this is? Your [editor’s note] is very unsatisfactory. Calling Brian Barbata’s drivel (ethically objectionable AND historically inaccurate, re: pyramids building) “ideas that should not be safely hidden from debate” is ludicrous. Not publishing trash is not the same as “suppression”. His opinion is blatantly racist, anti-Black, and oppressive, and does not invite any sort of intellectual debate that would be enlightening. Having to defend against such disgusting comments by people you call in “the community”—when in fact your choice to entertain such racism as just another “opinion” disregards the humanity of alumni and student community members who are descendants of enslaved people—only wastes our time and energy. We could be having debates about how to pay reparations or the insidiousness of white supremacy under liberal guises (like the meaningless “interhuman harmony” that letter-writer Frank Rycyk promoted) or the challenges and success of anti-racist and anti-capitalist solidarity. Instead, regressive decisions like yours mean we are re-litigating again and again the utterly basic premise that slavery is evil. The fact that that evil was normal and was participated in for economic self-interest does not mean that it was justified or necessary or something we should “get over”, as Barbata claimed. That is not new; there is nothing to be learned from this.

Your non-apology is another sign of your whiteness and the whiteness of Brown University and all its associated institutions. Own up to the harm you perpetrated and take actual accountability. Do better.

—Tanya Nguyen ’13

New York, N.Y.

“Northern Aggression” represents another in a long string of mea culpa diversity pieces and self-flagellation by Brown over the history of slavery. What’s the point of all this effort at Brown? The article moans that slavery was contrary to “our founding values.” But our founders were all slavers, one way or the other. If you were successful, you participated. I dare say, if the Brown family had turned their backs on anything to do with slavery, the University would not exist. Only a fool in the 18th century would have done that.

In the context of the day (over a couple of thousand years), slavery is totally understandable and clearly necessary. You weren’t going to hire 100,000 men to build the pyramids at a “living wage” with health care. Since forever, if a society could enslave other people, it did it. No major society was left out. In America, we’re sorry, but it was what it was. Everyone should get over it.

—Brian Barbata ’67

Kailua, HI

Are Brown symposium scholars still fighting the Civil War? The article “Northern Aggression” in July/August would suggest “yes.” Recently I had the pleasure of joining a history tour with both Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War and Sons of Confederate Veterans of the Civil War on the same bus. We all got along together quite well. I would like to suggest that small actions, such as organizing this mixed bus tour, can go a long way toward bringing people together. Creating interhuman harmony seems to me to be a much more productive goal than fighting racism.

—Frank Rycyk ’66

Jefferson City, Mo.