A woman takes a private elevator to an ultra luxurious Manhattan apartment with a wraparound terrace and double-height living room. One imagines at first that this is an athleisure-clad girlfriend, or a wife, or perhaps a personal trainer to the magnate who lives within. But no: This woman is a professional stretcher. And the very rich man (played by the distinctly posh actor Damian Lewis) who is being stretched in his multi-million dollar home is not someone I am viewing from my apartment with a telescope. It’s the next best thing: a set piece in the Showtime series Billions, now in its fourth season.

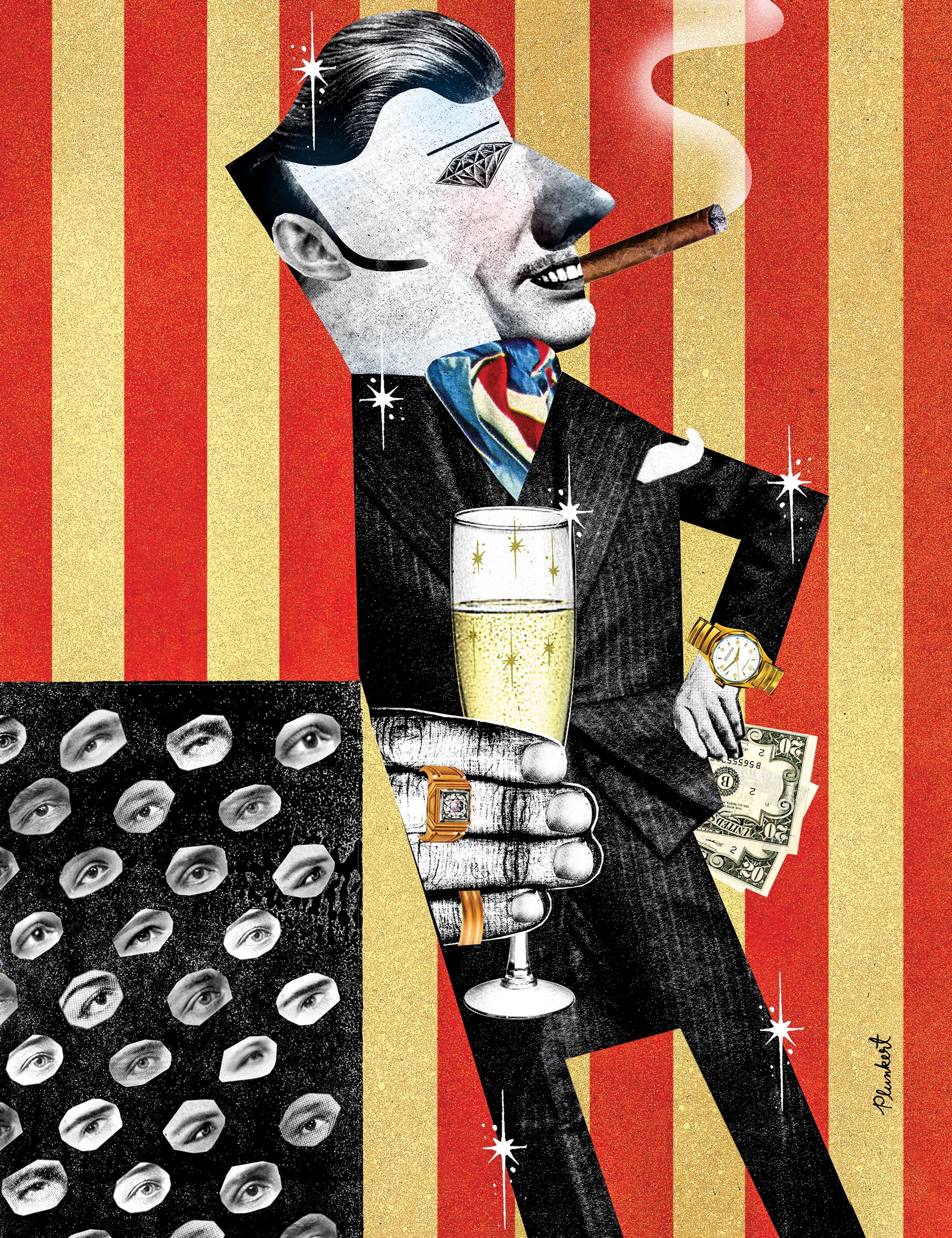

Why do I—and many others, as Billions is the channel’s second most watched show in its history—thrill to this glimpse inside a glass-encased condo with poured concrete floors? For the same reason we are watching this television show to begin with, along with the similar programs Succession, The Crown, and Empire. I call this genre “one-percent television” and sometimes also “bling porn.”

One-percent TV has taken off for many reasons. Possibly the most interesting: I believe it to be the result of the middle class’s increased social distance from the rich. “As the rich have gotten far richer, they’ve also become less recognizable and legible,” says Shamus Khan, professor and chair of Columbia University’s sociology department and author of a book on private school, Privilege. As a result, he says, these shows give us “insight into those around us who, with increasing inequality, have somehow become foreigners.”

After all, those in the one percent average over 39 times more income than the bottom 90 percent of the country. Think about that. And those in the top 0.1 percent have 188 times the income of the bottom 90. These people’s tastes and needs shape and deform our major cities, forcing up rents. They make even children’s parties into absurd luxury affairs and, yes, make our colleges places that compete over the quality of cuisine in the dining halls. They design both our corporate culture and the tech interfaces we work within. Yet their lives are so mysterious that we are left to wonder what makes them tick.

These people’s tastes and needs shape and deform our major cities...They design both our corporate culture and the tech interfaces we work within.

The desire of the merely middle class—or, indeed, the merely upper middle class—to decode this dominating new super elite explains why we binge on these shows. It’s also most likely why we spent much of this spring poring over the transcripts of celebrities scheming to get their kids into prestige colleges at any cost. It’s why we read New York Times real estate pages, and why teens follow luxury hotel photography by Instagram influencers.

Our thirst for insight into these “foreigners” is one reason one-percent TV trades in incredible specificity: the hedge fund office photography is by Gregory Crewdson, the designer watch is by Patek Philippe, the dinner is at exclusive Momofuku Ko, the sweaters are truly Loro Piana. These name-drops, along with uber-rich behaviors and language that are depicted in anthropological detail, give audiences the sense that they are unlocking the secrets of the extremely wealthy barbarians at our gates.

There are other reasons for our interest in oligarchs with ethical challenges (the shows feature laissez-faire attitudes to dreadful behavior including—spoiler alert—manslaughter). Today, our country partakes in a seemingly endless celebration of wealth, imagining that affluence is equivalent to talent or even value itself. The idea, says Khan, is that the wealthy “are exceptional people.” Having money and being of worth are equated: it’s a “particularly American elision that makes observing these people of interest.” As the critic James Wolcott wrote in Vanity Fair of today’s shows about the most affluent, “It’s floating and caressing, immortalizing.”

Nothing exemplifies the false equation of wealth and worth better than the one-percent shows that starred (and continue to star) our president. It started with his reality show The Apprentice, which ran in different iterations for over a decade. Perhaps more than any other show, The Apprentice established the genre norms of one-percent TV, from its star’s insistence that “My jet’s going to be in every episode” to his treatment of television employees as if they were plaintiffs in a Maoist show trial.

There’s a third reason why we tune into one-percent TV. Even as we suffer greater income equality than ever, we strive to maintain our fantasy of American opportunity. Our mass addiction to everything from prestige billionaire shows to the Real Housewives franchise telegraphs our need to identify upwards in terms of wealth—rather than with people like us, or, even worse, with those who are struggling. We’d rather pretend that we too will one day have our own human stretcher than spend our time thinking about addressing the many structural inequalities that keep even more modest dreams out of reach.

It’s that way for me. I use these sorts of shows as virtual painkillers, marinating in the fantasy of upper class excess. As Khan theorizes, I feel that when I am watching these dramas I am somehow unlocking the interior lives of my urban oppressors in the glass-clad buildings that occupy miles of my native New York City.

Of course, the rich have always been with us and shows like The Crown offer a kind of distorted hindsight. At $150 million per season, the Netflix show lavishly depicted another twisted one-percent family, the British royal one. The decadent, colonialist, snobby, and sometimes downright racist royal family is given the kind of ambiguous enshrinement that viewers seem to crave.

In older representations, the two meanings of worth—monetary wealth and moral excellence—were less intertwined, or more complicatedly entwined.

In its first season, in a meta-touch, The Crown depicts England’s first televised coronation. In sharing its excessive pageantry with the citizenry via TV, the monarchy distracted them from their postwar rations and hardships—much as today’s shows like The Crown distract us now. Historical bling TV reminds us that our fascination with the super-rich is nothing new. But has it increased? We might wonder how it could not have: the hyper-rich are omnipresent in the largest American cities and in our political and popular culture, exemplified by the literally gilded trappings of our president himself.

Older representations of wealth had a different timbre. Viewed through what the singer Michael Franti once called the cathode ray nipple, Falcon Crest and Dynasty featured rich people who were often unrelatable baddies. On Upstairs, Downstairs—a PBS hit and British import that ran in the 1970s—the bluff, friendly maids and cooks were presented as morally superior to their snooty social betters, reflecting the New Left class consciousness of the U.K. in that period. Perhaps, back then, the two meanings of worth—monetary wealth and moral excellence—were less intertwined, or more complicatedly entwined.

A further point: The riches on these shows weren’t usually produced by entrepreneurial zeal. Wealth was more often inherited, leaving the viewer less likely to fantasize that they might actually become one of these scions.

But now, if we’re honest with ourselves, we suspect one day we too will luck into becoming a hedgie. This delusion may be the strongest argument for not spending our leisure hours zoning out on one-percent TV. We use it to forget our anxieties—even as the truths underlying it cause those anxieties in the first place. In a perfect world, we would jettison this self-imposed paralysis to fight income inequality in all its guises.

I think we can continue to watch, and even enjoy—but with a more critical eye, one that inspires us to fight against the institutionalized advantages these programs joyfully depict, including tax and criminal loopholes for the richest. Let’s go ahead and watch, and allow billionaire TV to give us the rage to get out the vote. If we’re successful, one day the

gleefully one-percent TV show streaming from our capitol right now could

ultimately find itself canceled.

Alissa Quart ’94 adapted these ideas from her book Squeezed: Why Our Families Can’t Afford America, just out in paperback. Quart is the executive director of the Economic Hardship Project, a journalism nonprofit, and is teaching advanced writing at Brown.