RaMell Ross’s textured, intimate Hale County is both a lyrical love letter to a black Southern community and a challenge to many viewers’ preconceptions.

Early on in Hale County This Morning, This Evening, the camera—more or less static in a corner—watches Kyrie, a 3-year-old black boy, pick up a toy gun and run around his living room. The shot pans and drifts dreamily in and out of focus while Kyrie runs toward the viewer and away, across the room and back. He puts the gun down and keeps running. His breath is heavy, his steps tottering and earnest. The scene lingers with Kyrie for almost three minutes. Eventually he comes right up and puts his face into the lens, laughing. The screen goes black. Then Kyrie runs away, out of focus.

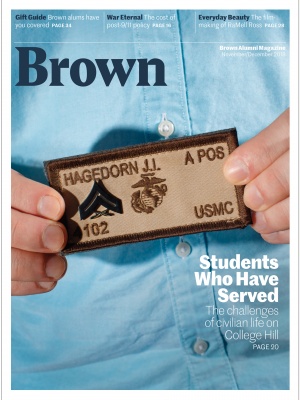

Released in theaters in mid-September, Hale County is the first film from RaMell Ross, a Mellon Gateway Fellow and assistant professor in Brown’s Visual Arts department. In 2016, Ross became the Brown Arts Initiative’s inaugural professor of the practice, teaching photography classes while he finished editing his movie about life in the rural Deep South.

The sequences this approach yields are meditations on what Ross calls “the epic banal” of blackness—images of the subdued beauty in these everyday black lives that subvert and transcend many viewers’ preconceptions of race and class. Daniel’s sweat drips onto the floor as he dribbles a basketball, followed by the patter of rain on the ground. A kid stands up on a horse and calls out to friends, laughing. A little girl holds up a homemade electric circuit, lighting up the mini-light bulb to show her friend and saying: “Y’all do this in science yet? Y’all gonna do this in science.”

These are images, Ross says, that are new to American media culture. They’ve always existed, but not necessarily in cinema. Traditional documentary storytelling tends to depict the lives of people of color in terms of their struggles. Ross calls this “the silhouette of blackness”—cultural perceptions of American blackness “backlit by history.” Ross did not want his art to be confined in this space, and he didn’t want the stories of his subjects—boys he had coached, taught, and befriended—to be told in that stereotypical way.

Ross, who grew up in a suburb of Washington, D.C., first moved to Greensboro, Alabama, nine years ago, working as a basketball coach and photography teacher. Fascinated by the landscape, he took photographs, then began filming his friends. He wasn’t thinking about what he’d do with the images he collected—he was seeking, rather, to investigate daily life in this quiet, predominantly black Southern community. “I didn’t expect to make something this grand,” he says. “But the more I filmed, the more I realized there was potential to get as close as I could to understanding someone’s point of view through my perspective.”

The result is an ambitious movie that eschews traditional narrative structure in favor of sequences of moments that capture a poetic loveliness in both lives and landscape. Its dreamy filming and editing techniques are punctuated by intertitles—such as “What happens when all the cotton is picked?”—that both contextualize the scenes and challenge the viewer. In the process, Hale County creates its own cinematic language, an achievement honored with a Special Jury Award for Creative Vision at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

The film focuses on two young men, Daniel and Quincy, and their friends and family. Ross had taught Daniel on the court and Quincy in the classroom. He considered them friends, and says he would have spent time with them whether he was filming or not. In Daniel, obsessed with basketball and driven to succeed on the court and in school, Ross says he saw a version of his younger self. With Quincy, a good-natured and goofy young father, he felt comfortable and at ease.

In the years he spent filming them, the camera became a quotidian presence. Ross used it merely to “look,” he says, rather than to capture any particular narrative. “I’m using the camera as close to fluidly with my consciousness as possible,” he says, an attempt “to participate in their lives.”

At the same time, Ross directly confronts the legacy of racism in Hale County, along with racist depictions of blacks in the media, with scenes like the one of 3-year-old Kyrie—Quincy’s son—running around with the toy gun. “When you’re not given a narrative, everything that you think has less to do with what’s happening in front of you and more to do with your experience,” Ross explains. “You create the meaning. If you’re thoughtful, you’ll think about why you’re thinking that: Is it true? Or am I putting my own narrative on this kid?”

Another shot in Hale County is a long, slow-motion drive-by of a cotton field stretched out indolently across the landscape. “It’s the fact that here you have to drive by a cotton field every day to go to work and then just become desensitized to the cotton field’s history,” Ross says.

In 1941, the photographer Walker Evans and the writer James Agee published their famous nonfiction book about Southern sharecroppers, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Though they focused on Hale County, there is not a single image of a black person and barely a mention of the black community that also lived there. Ross’s film offers another view.

“The ultimate goal,” Ross explains, “is to create new meaning, to lengthen the spectrum of what it is to be a person of color in the historic South.”