What Would You Do?

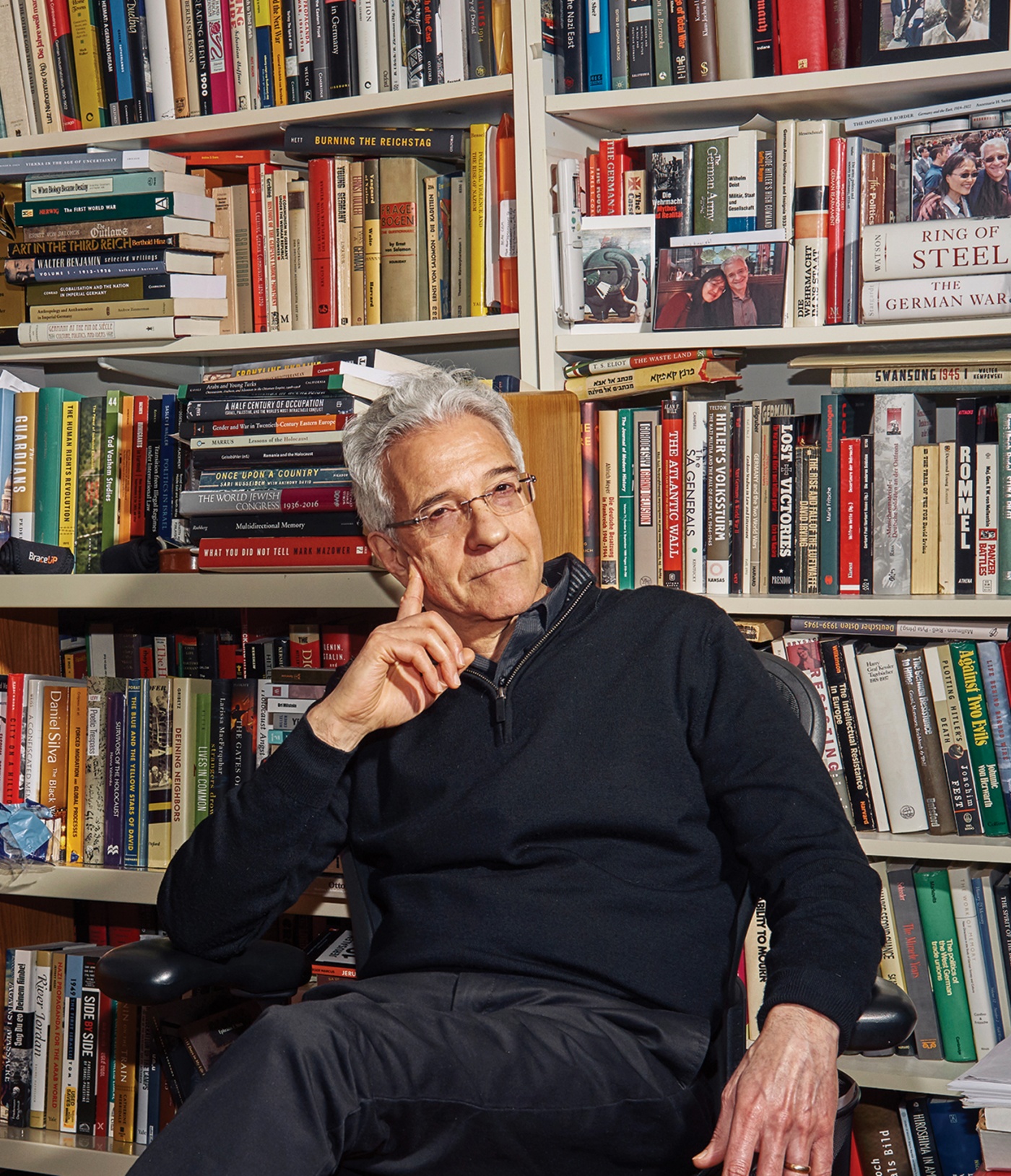

History professor Omer Bartov asks why, despite living as neighbors for hundreds of years, Ukrainians and Poles helped slaughter some 10,000 Jews during World War II.

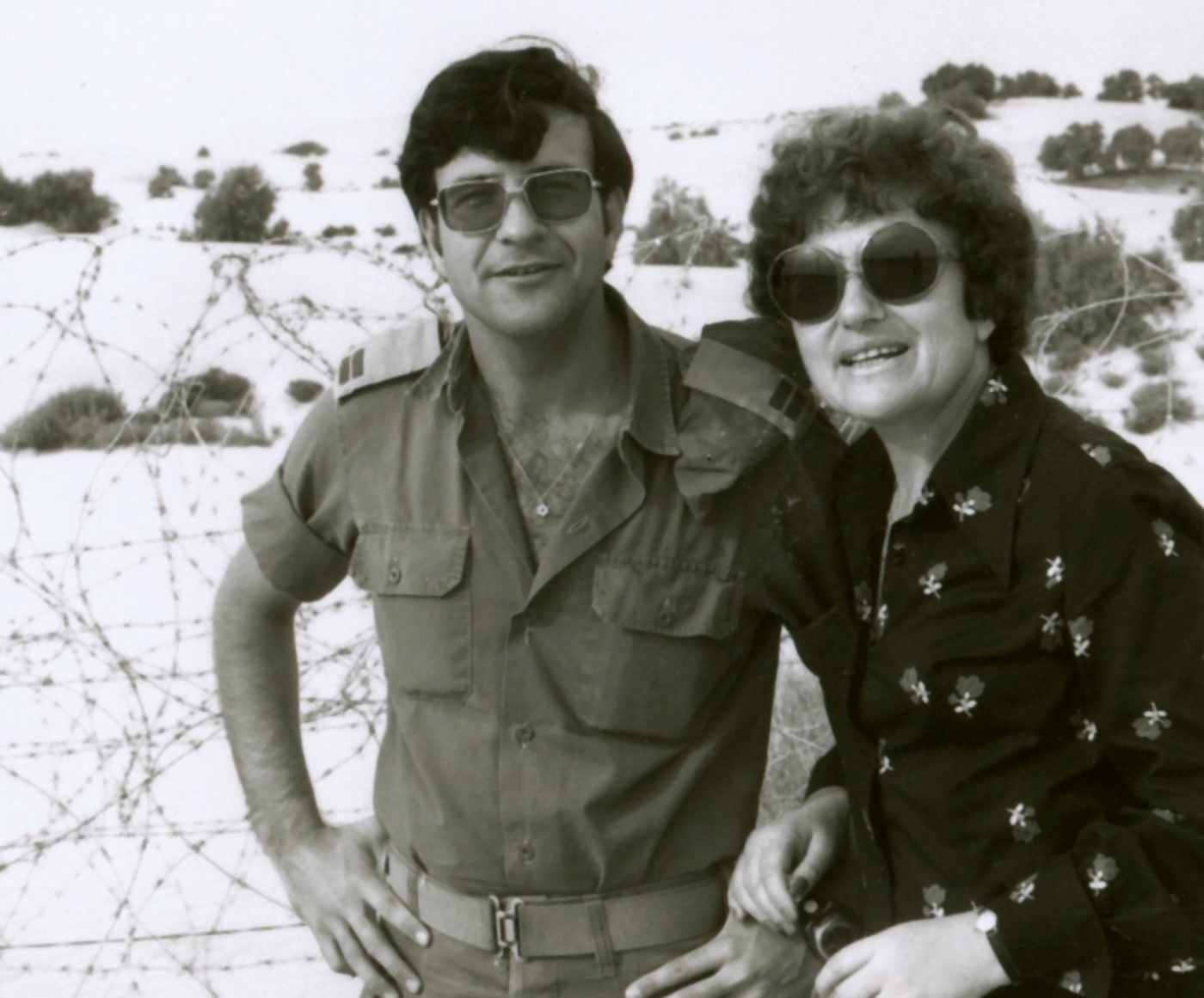

The journey began, in a sense, with a casual conversation four decades ago. Omer Bartov, a young reserve officer in the Israeli army, was on patrol near the Golan Heights when an older soldier, who’d been a boy in Romania during the Holocaust, asked what he did in civilian life.

“I am studying modern history—Nazi Germany,” answered Bartov, then an undergraduate at Tel Aviv University.

“You know, there are people who’ve made the Holocaust into their profession. Can you believe it?” the older soldier said. “I was there. And now there are people who are getting tenure on the Holocaust.”

“It just was weird and strange and unnatural to him,” Bartov now says, “that an event so personally traumatic to him was also the occasion for people to have a career. He found it, I guess, disturbing. And I kind of agreed with him.”

A dozen years later, Bartov, who is the John P. Birkelund Distinguished Professor of European History at Brown, was writing an essay on several Holocaust-related books when he experienced an epiphany: “I realized that all those years I’d been reading about the Holocaust, thinking about it, but I’d never acknowledged it to myself. And there was something that I needed to deal with.”

That something culminated in the January publication of Anatomy of a Genocide: The Life and Death of a Town Called Buczacz, a project 20 years in the making. Bartov’s interest in the Ukrainian town of Buczacz (pronounced Buchach) is partly personal: it was his mother’s childhood home, though she left years before German soldiers invaded and began slaughtering Jews with the help of local Ukrainians and, to a lesser extent, Poles. The town also became an historical laboratory for a larger question that has long troubled Bartov, a pioneer in the field of comparative genocide studies: how, as in 1990s Rwanda and Bosnia, can ethnic groups that have lived together for centuries suddenly turn so savagely on their neighbors?

His research took him to nine countries, where he interviewed survivors and witnesses. He taught himself to read Polish, Ukrainian, and Russian so he could mine newly available archives. He pored over handwritten Yiddish diaries, German court records, centuries-old Latin documents, and the Hebrew stories of the Israeli novelist and Nobel Prize-winner Shmuel Agnon, who had once lived in Buczacz.

He discovered a complicated history of both coexistence and upheaval. In Anatomy of a Genocide, Bartov writes, the Nazi-supervised genocide of 1941–43 became “a communal event both cruel and intimate, filled with gratuitous violence and betrayal as well as flashes of altruism and kindness.” As neighbor turned on neighbor, Jews were forced to bargain, beg, and flee for their lives. Nearly all were murdered, including everyone in Bartov’s extended family who had stayed behind.

“Tell me about your childhood,” Bartov asked his 71-year-old mother on a 1995 visit to Tel Aviv. In Anatomy of a Genocide, he describes today’s Buczacz as “a shabby post-Soviet backwater ... Poor, derelict, depressed.” But his mother, who left for Israel in 1935 with her Zionist father and the rest of her immediate family, remembered a quaint, tranquil place where Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish children often played together and spoke one another’s languages. “Had she stayed another four years, she might never have come out,” Bartov notes, “and I might not have been born.”

Though they talked of returning to Buczacz together, his mother died three years after their conversation, and the trip never happened. Bartov, now 64, instead undertook the pilgrimage on his own, curious, in part, about his own fragmentary family history. He found only a single document related to his family’s emigration. So he turned his attention to the ongoing debate about the nature of genocide.

According to Bartov, many scholars believe that “in order to kill large numbers of people, especially in a modern society, you need to create a certain mechanism of both dehumanizing the prospective victims and distancing the killers from the victims.” In Nazi Berlin, for instance, neighbors saw Jews being taken to a train station, “usually with their little coats and with their suitcases. You don’t know what happens to them, and you don’t ask too many questions.” In the camps, where the gas chambers awaited, “the people who kill them don’t know anything about them, and don’t really have much contact with them,” effectively compartmentalizing the process.

“The problem with that model,” Bartov says, “is that most of the Jews killed in the Holocaust were living in Eastern Europe—and were killed in Eastern Europe,” only about half in extermination camps. “So, what happened to the other half?”

Anatomy of a Genocide zeroes in on what Bartov calls “the encounter between the perpetrator and the victims.” Holocaust historians have used the categories of perpetrator, victim, bystander, and rescuer, and the Auschwitz memoirist Primo Levi famously described a “gray zone” in the camps and the ghettos in which collaboration became necessary for survival. But in the intimate setting of a town such as Buczacz, with a 1939 population of 15,000, Bartov argues that “everything is a gray zone. There is no other zone. Everyone is in it.”

Even the line between perpetrator and victim can blur. Take the case of a Jewish survivor Bartov interviewed in 2002, a former partisan who attacked Ukrainians for denouncing Jews to the Germans. Bartov later discovered testimony the man gave to a German court in 1968 in which he admitted to having been a Jewish policeman.

“In Buczacz, Jewish policemen, as in many of these towns, helped Germans and Ukrainians round up Jews and take them to the killing pits,” Bartov explains. “And I thought, ‘Did he lie to me?’ No, he didn’t. He just didn’t tell me the whole story.” The man was a policeman until the Germans, in 1943, turned on the Jewish police. Some escaped to the forests and became partisans. The common conception, Bartov says, is, “‘The policemen, they were

terrible people. The partisans, they were great.’ They were the same people very often! These were young men, and sometimes women, who wanted to survive—and they did what it took to survive.”

When he began researching Buczacz, Bartov says, “the idea was really to write a biography of a town through the eyes and words and experiences of people who were there.” During the period of World War II and its immediate aftermath, amid the turbulence of alternating Soviet and Nazi invasions, Bartov uncovered “more and more fraught and complicated and urgent voices.”

He says he believes, for example, that the Ukrainian and Polish women he interviewed were being honest about “how horror-stricken they were” to see “their Jewish girlfriends being carried out or killed. And I also think that some of them did actually try to help. But when they say, ‘We, all of us, Poles and Ukrainians, did all we could to help,’ I know that’s not true. And they are either saying it because they would like to remember it that way, or they think that’s what I should hear, or they just don’t want to tell the truth and accuse their own people.”

Anatomy of a Genocide has been widely praised by other Holocaust scholars. “I had waited for that book for a long time,” says Saul Friedländer, a celebrated historian and memoirist of the Holocaust who was one of Bartov’s teachers at Tel Aviv University. He calls Anatomy of a Genocide “an exemplary microhistory … the best we have.”

“What impressed me particularly,” Friedländer says, “was the detailed descriptions of the relations between the Ukrainians, Poles, and Jews,” which explain “in great part, very convincingly, the explosion of murderous hatred.”

Bartov is distinctive for his “voracious historical curiosity,” says Maud Mandel, Brown’s dean of the College and a Judaic studies scholar who in July will become president of Williams College. “Omer has an idea of something he’s curious about, and then he brings people together. He has these multiyear international conversations. It creates an intellectual excitement that the Brown community can participate in.”

While researching the Buczacz book, Bartov initiated “Borderlands,” which convened historians, political scientists, sociologists, and others studying Eastern Europe and produced an essay collection that he coedited. He has since launched “Israel-Palestine, Lands and Peoples,” another interdisciplinary project, and teaches undergraduate seminars linked to these gatherings at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, bringing in students to interact with scholars. Daniel Wayland ’18, a history concentrator who has taken Bartov seminars, says that the historian brings to the charged subject of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict “a measured perspective and cautious optimism that’s very heartening.” Bartov is also spearheading an exchange program to pair a half-dozen undergraduates with Jewish and Arab students at Hebrew University beginning next year.

In the field of genocide studies, Bartov has helped turn the focus from top-down examinations of their political mechanisms to the quotidian decisions of individuals. Genocide imposes “a sense that you have no choice,” he says. “And maybe in the [larger] scheme of things that’s true. But on the ground, where people are actually living or dying, people always have a choice. They may be very small choices, and they usually are bad choices, but they have choices.”

Not that the moral course is easy to discern. A Ukrainian peasant caught sheltering Jews might have his entire family murdered by Ukrainian police. “It’s very hard to make judgments,” Bartov says. “Ultimately, you end up thinking about yourself and your own neighborhood. What would you do if the police came? If they knocked on the door, would you open the door?”

Asking such questions, he says, takes genocide “out of this metaphysical sphere. It brings it down to earth. It doesn’t make it pretty. It makes it even more horrible because people, most of whom are not particularly good and not particularly bad, act in ways and have to make choices that are completely impossible for us to consider ourselves making. And yet we are no different from them.”

Bartov, a naturalized U.S. citizen, adds a cautionary note about today’s fraught national politics. “When you identify a group as being insidious, as being less than normal, then this is the first stepping stone toward violence. The political discourse in this country in the last couple of years has done more and more of that with greater and greater abandon,” he says. “With a country that has so many millions of guns, certainly it is dangerous, and should be stemmed.

“When I started this book,” he continues, “it had nothing to do with what is happening today in the United States. But when you see this kind of writing on the wall, you should take care. And when you see what happened in Buczacz, you know it starts also with these kinds of hatreds, resentments, little issues that are internal to each community, that are given license, that are legitimized, that are mobilized by larger political forces. And once you set them loose, it’s very hard to stop them.”

Julia M. Klein, a cultural reporter and critic in Philadelphia, has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Mother Jones, The Nation, Slate, and other publications. Follow her on Twitter @JuliaMKlein.