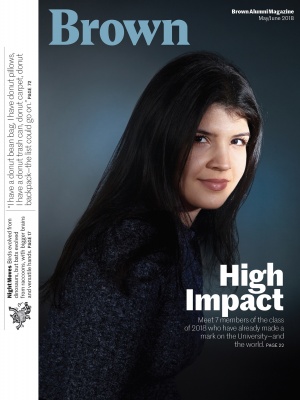

Nearly 1300 undergraduates will walk out through the Van Wickle Gates this year. Here’s a small sampling of the many exceptional members of the Class of 2018 who, through their creativity, their scholarship, and their dedication to serving others, have already made an impact on their world—and ours.

Mursal Gardezi

The Real Deal

Mursal is the real deal,” says Christopher T. Borne, director of the Weiss Center for Orthopaedic Trauma Research at Rhode Island Hospital. “She has the ethos and capacity to make a meaningful impact on society.”

Gardezi, along with principal investigators Borne and Assistant Professor of Orthopedics Dioscaris Garcia ’12 PhD, has been devising a speedier test for surgeons to test for bacterial infections. Current tests take up to two weeks and are, as Borne puts it, “fraught with inaccuracies.” Gardezi, he says, has gotten a test down to 35 minutes—potentially revolutionizing the way these infections are treated. Her work has already been presented at national conferences.

“I was very, very fortunate to get into Brown,” the soft-spoken Gardezi says. Born in India to Afghani Muslim parents who had fled the Taliban, Gardezi notes that as refugees the family was “sometimes homeless, not always having food.” They made their way to California, where Gardezi entered public kindergarten, despite speaking only Hindi and Farsi. Her dad, a former army general from a wealthy family, became a cab driver. “We live low-income and we’re supported by the government to this day,” Gardezi says.

Growing up as a Muslim immigrant, Gardezi was once threatened by a group of angry boys on the way home from elementary school. Her mother stopped wearing a hijab, to avoid being a target. In high school Gardezi earned a 4.6 GPA and won awards for community service leadership. She knew she wanted to study biology and become a doctor-researcher. Gardezi applied to Brown and was offered a full Sidney E. Frank scholarship and a spot in the New Scientist Catalyst pre-orientation program.

Gardezi credits her success to the extra help Brown offers low-income students from historically underrepresented groups. “Without Catalyst,” she says, “I don’t know if I would have passed. It’s that drastic.” She also met friends from similar backgrounds. “There are people like me who need to be here [at Brown], who offer a different perspective,” she says. “If there’s no one to have that voice in research”—such as studies of differences in how breast cancer affects African American women—“then that research isn’t going to be done.”

Gardezi, who spends hours peering into a specialized microscope, throws around such words as “osteomyelitis” and “polymerase chain reaction,” but she’s still able to describe “biofilm” in layman’s terms: “You have this big clump of bacteria—they start talking to each other and start behaving differently. Antibiotics can’t penetrate the gooey weird stuff that they secrete.”

Outside the lab, Gardezi does community service—mentoring low-income high school students, cuddling drug-addicted babies at Women’s and Infants Hospital, volunteering at the Rhode Island Free Clinic. She explains she’s gotten a lot of help and, as she did in high school, wants to “pay it back and pay it forward.” —Louise Sloan ’88

Tin Dang

In and Out of the Lab

Like most of the class of 2018, Tin Dang arrived on campus clueless about his meal plan.

He didn’t yet know that Jo’s was the place to go late-night for fried chicken sandwiches and that the lines in the Blue Room usually peaked around 4 p.m. when students could pay with meal swipes instead of points. He was so confused about meal swipes that he lost 30 pounds during his first semester.

It never occurred to him to ask fellow students or faculty about the school’s seemingly meager meal plan. As a first-generation college student, he says he had “learned how to figure everything out for myself.”

Dang has since gone from a student who had “no idea how Brown worked” to one who makes it work for others. As a coordinator for the Sidney E. Frank Scholars Association, which assists low-income students who have received the school’s Sidney E. Frank scholarship, he helps facilitate programming for the recipients and eases the transition of first-years into Brown. He advises students on extracurriculars and courses as a Meiklejohn adviser, and spent two years as a volunteer for the Swearer Classroom Program, making weekly visits to William D’Abate Elementary School to tutor Spanish-speaking students.

“Growing up,” Dang says, “I never thought what I had to say was really important. Just knowing what I say can have an impact has changed that.”

Dang says he’s leaving Brown with a newfound confidence, which he attributes to these mentorship roles, along with a healthy heaping of humanities courses.

These past four years, Dang has zigzagged between departments, balancing pre-med requirements with courses in anthropology and Hispanic studies. Dang’s looking to life after Brown with the same desire to try it all. After a summer working in a lab at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Florida, Dang felt ready to explore the world of health care outside the four walls of a laboratory. He returned to the center the next summer to conduct educational outreach on colorectal cancer for the elderly.

Last summer, when he came across a training curriculum on palliative care for physicians and nurses in Vietnam, he thought this approach, which treats both the physical and mental pain of those with life-limiting illnesses, might allow for a deeper connection with patients. And as a Vietnamese immigrant—he, his parents, and sister settled in Clearwater, Florida, when he was five years old—he is drawn to the idea of returning to his home country. He grew up speaking Vietnamese at home but felt a constant need to “hide” his roots at school.

Dang says Brown provided him “an opportunity to reconnect with (his) identity,” home to more first-generation and low-income Vietnamese students than his “really rich and white” high school. He’s mulling booking a plane ticket to try and work for the doctor who introduced the palliative care system in Vietnam before heading to medical school. —Rebecca Ellis ’18

Aidea Downie

Let’s Be Honest Here

When Aidea Downie, the daughter of Jamaican immigrants living in a working class community on Long Island asked her college counselor about Brown, his answer was blunt: “Let’s be honest, here. You’re probably not going to get in.” When he tried to steer her toward community colleges, Downie’s mother started shouting from the back of the room: “She’s going to Harvard! She’s going to Harvard!”

Downie laughs. “People from low-income backgrounds, we’re told all the time, either explicitly or implicitly, that some spaces of privilege don’t belong to us; that we shouldn’t even dream about accomplishing certain things.”

When Downie was 14, her uncle, a convenience store owner, was mugged and shot dead on his way home with his earnings. It was a turning point in Downie’s life and the life of her family. She decided she wanted to become a prosecutor so that she could be part of creating a safer community.

Then, her first year at Brown, Downie took Professor of History Amy Remensnyder’s class Locked Up: a Global History of Imprisonment and Captivity, and everything changed again. “That course introduced me to the structural inequalities that people go through that make them vulnerable to going to prison,” Downie says. “The thing that I’d been trying to be for the last four years of my life I didn’t want to do anymore,” she says. “I felt really lost.”

Remensnyder also taught Brown-level classes in a Providence-area prison, and Downie was inspired. This struck her as a better way to help. So, while still a first-year, she started a Brown chapter of the Petey Greene Program, a national nonprofit that trains college students to be teaching assistants in prison education programs. The popular program, now in its third year, has about 50 tutors and sponsors panels on topics like restorative justice.

In summer 2016, Downie used an Undergraduate Teaching and Research Award to assist history professor Nancy Jacobs on two research projects in Kenya. She brought Angela Davis to speak at Brown in 2017, and through the Swearer Center, she spent last summer working for the New York Division of Human Rights.

Downie has held a variety of jobs to support herself and to send money home to her grandmother, like cataloging films for anthropology professor Lina Fruzzetti and helping anthropology professor Kay Warren research police brutality. But the work she’s done in the prisons stands out. “It’s been amazing to help someone learn how to read a book, conquer fractions, have that happy moment when they get their GED.” Downie has enrolled in the Urban Education Policy master’s program at Brown, and after Commencement she’ll be regional manager for the Petey Greene Program. Next, law school: “I want to work to change the criminal justice system and find ways to do that tangibly through laws.” —L. S.

Eric Rosen

Computer Science for Everyone

Eric Rosen wants kids to know that coding is cool. As the president of Brown’s Google Ignite CS Initiative, he gets Brown students to teach coding and robotics in local schools. Whether it’s creating a program that turns English into Pig Latin or explaining how Google Maps decides the best route for people to take, Rosen brings activities into the classroom that he hopes will make computer science fun and accessible to everyone.

“I love actually getting to be a teacher because I’m learning, too,” Rosen says. “It’s less about teaching students a coding language, and more about showing them how computer science relates to everything around them.”

Outside the classroom, Rosen has spent a year and a half developing his own research projects in the Brown Robotics Lab. Starting as a sophomore, Rosen worked with graduate student David Whitney to design an algorithm that allows robots to decide when to ask questions in response to human commands.

“The goal is for robots to know what they themselves are confused about,” Rosen says.

A person might point and ask a robot to pick up a cup, but if there are two cups next to each other the robot will ask which one, Rosen explains. The farther apart the cups, the less likely the robot will have to ask a question.

The idea of improving human-robot interactions fascinated Rosen, leading him and Whitney to try and figure out how people could work more efficiently with robots from afar. “We wondered, ‘Can we use how humans move around to make a really intuitive way for the human to control the robot?’” Rosen says.

Rosen and his team paired robots with virtual reality software, allowing the robot to respond directly to human movement. Strapping on a Vive headset and nunchucks in the Brown Robotics Lab, Rosen can make a robot in an MIT laboratory 41 miles away stack a series of cups perfectly, as one video test shows. The headset allows Rosen to view a representation of what the robot itself sees. By using the nunchuck in his own hand to pick up the cup, which is three dimensionally projected in front of him, the robot’s arm will follow suit.

For now, robots and humans in Rosen’s lab are working together to practice folding laundry, but bigger plans are in store. The goal is for robots and humans to join forces on difficult but potentially life-saving tasks too dangerous for people to do on their own, such as disabling a malfunctioning nuclear reactor.

After spending much of his undergraduate career engaged in PhD-level research, Rosen will continue his work with the Brown Robotics Lab following graduation as a postdoctoral student. Still, Rosen keeps the door to his lab open to the high school and middle school students he works with and is always eager to give them a tour and test out equipment.

“Students explode for robots,” Rosen says. “I want my passion and love of CS to bleed into them.”—Jack Brook ’19

Sierra Edd

Politics and Art

Born on the Navajo Reservation in Shiprock, New Mexico, Sierra Edd has been making art since she was six. Her parents are both artists, and from a young age Edd and her three sisters started selling their paintings and drawings at the Santa Fe Indian Market. Over spring break, she and her sisters painted a commissioned mural in an Albuquerque hotel depicting Navajo cosmology and the creation story.

Activism is also part of Edd’s DNA. At school in Durango, Colorado, she was one of the leaders of the Prejudice Elimination Action Team. Her mother was a big influence. “I was really aware growing up of the different issues facing Native communities and other people of color,” she says. At Brown, she decided to concentrate in ethnic studies to learn more.

Awarded a Mellon Mays Fellowship, Edd researched border town violence near Farmington, Colorado, which borders the Navajo reservation. She interviewed people who had lived there for more than twenty years, including her uncle, for an oral history project and was surprised to hear about the violence he faced in high school—like having his hair lit on fire.

“That was pretty wild learning my own family history,” she says. She also did archival research in which she learned of the murders of two Navajo men in the 1970s and the subsequent boycotts and protests that took place. “All this information was just really shocking to me, because nobody talks about it.”

Edd’s studies fueled her artwork, which was included in the “Native Re-Appropriations” exhibit at the Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America at Brown, which attempted to confront stereotypes of Native people. “Native art is, and will always be, political,” she wrote on her website (www.eddgirlart.com/sierra). She contributed poems to The Round, a Brown literary magazine, and to the AsUs journal online. Synecdoche Publishing, based at Brown, published Red House Wanderings, a book of her painting, photography, poetry, and graphic art. Three of Edd’s paintings were featured in “We Are Native Women,” a show at the Rainmaker Gallery in England.

As coordinator for the Brown Native American Heritage Series, she has brought many Native American speakers to Brown. She was also one of the leaders in the push for Indigenous People’s Day at Brown.

After graduation, Edd plans to head home to paint with her sisters and, as she does every summer, sell artwork at Indian Market. Then it’s off to UC Berkeley in the fall to start a PhD program in ethnic studies. Her ultimate goal: to be an educator for Native people and “build a curriculum that is non-Western, uses indigenous knowledge, is focused on restorative justice and decolonization and all these resistance models of education that would be accessible to schools everywhere.”—Leslie Weeden

Anne Prusky

The Power of Language

Before arriving at Brown, Anne Prusky, a native English speaker from the Philadelphia suburbs, had mastered Hebrew and Latin. So she wanted to study another language. She chose American Sign Language (ASL), not because anyone in her family is Deaf (“I had never met a Deaf person before Brown,” she says) but because she thought it would be “way easier” than learning a spoken language. “I was super wrong,” she laughs. At the time she had no idea that ASL would end up being the focal point of her college career.

“I loved who it turned me into,” she later wrote. “When talking with my hands I was suddenly more expressive, braver, even funnier.” Prusky sought out new people to sign with, and in fall 2015 she founded the Brown University Sign Language Society, which hosts variety shows that include poetry, storytelling, and improv games involving the local Deaf community.

As a first-year, Prusky took Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology and fell in love. “It was amazing,” she says. She soon learned, however, that not enough courses existed for a concentration, so she designed her own, Socio-Cultural Linguistics (SCL), based on the languages she knew—English, Hebrew, and ASL—and their distinctive cultures.

Though she aligned herself with the Linguistics Department, she sought a broader perspective, wanting to study not just the technical systems present in language, but also “the real-life effects of language on society and society on language.” She was primarily interested in a multidisciplinary approach—delving not only into linguistics but into anthropology, sociology, psychology, Judaic Studies, and history as well. “In short,” she wrote in her proposal, “SCL is a way of understanding the human world through our most defining characteristic—the use of language.”

As part of the Engaged Scholars Program, which combines academic studies with “community-based, experiential learning,” Prusky worked in three different Deaf communities. As an intern for the Rhode Island Commission on the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, she helped coordinate data on Deaf students in Rhode Island schools. While working with the DeafYES! research team at UMass Medical School, whose goal is to make research studies more accessible to Deaf people, she was in a “fully signing environment” where her “sign-language skills jumped four feet.” She’s also been working for the Governor Henry Lippitt House in Providence as an accessibility intern, helping to make the museum more welcoming to the Deaf. She recently won a $2,000 grant to purchase new equipment and create an ASL museum tour.

After graduation, Prusky plans to pursue what she’s wanted to do since middle school: teach. She’s not sure yet if that will be at a Jewish or secular school or working with the Deaf. But one thing she does know: “I hope to be engaged socially and politically with Deaf folks forever.”L.W.

Adam Moreno

The Bird Lover

Adam Moreno passed out feathers to first grade students at the Paul Cuffee School in Providence and watched their faces turn to complete awe. It was the first week of April, and the students were learning about birds.

Since he first started working as an animal care volunteer at 14, Moreno has been obsessed with everything about birds—their colors and feathers and flight and how he could see them anywhere he went. In the fall of 2016, Moreno took Feathery Things, a history class offered by Professor of History Nancy Jacobs. It focused on how birds interact with human cultures in different ways. For his final project, Moreno began work on a bilingual field guide, written in English and Spanish, showcasing 33 birds found in Providence and using images from a local photographer, Pam Tesler-Howitt.

“A lot of people living in cities have the impression that there is no wildlife here because it’s a city,” says Moreno, who has concentrated in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology.

Moreno wants kids to appreciate the common birds they see around them every day and how these birds represent an important part of the landscape. Given that many people in Providence speak Spanish as their first language, Moreno felt it was important to gear his book toward Spanish speakers. In the field guide he writes of the epic migratory patterns of such birds as the Ruby-

Throated Hummingbird, which travels to Mexico and South America in winter.

“The idea is that migration is something that is wonderful and beautiful and should be admired,” Moreno says. “Borders are something we’ve set up arbitrarily, and moving and migrating is not something that should be looked down upon or make kids feel different or strange, but just a part of life. Birds don’t see country borders, they are going to go where they know home is.”

Moreno is working with the Cuffee school to launch a program that pairs Brown students with third and fifth graders for nature walks using donated copies of his field guide.

“My hope is that after the program students will continue to use the book and explore and learn new things,” Moreno says. “Because it’s written in both languages, they can read it with their families at home and involve them in their outdoor learning experiences.”

Outside his avian education work, Moreno has conducted ecological research in Panama and Costa Rica and is the president of the Brown Poler Bears pole-dancing club. Moreno performed blindfolded in the Brown Aerial Arts Society’s spring show in late April to two nights of packed audiences in Alumnae Hall. The Poler Bears exists to promote the athleticism and artistry of pole dancing and to combat the stigma associated with it, Moreno says. “If anyone comes to one of our shows, that’s immediately erased,” Moreno told the BDH in 2017. This fall, he’ll enter Ohio State’s College of Veterinary Medicine, where he hopes to learn to treat birds and other forms of wildlife.—J. B.