Alone Among Animals

Evolution explains a lot—but can it really account for human consciousness?

Kenneth R. Miller ’70, professor of biology, loves to gaze at the night sky. “Ask my daughters,” he says. “When they were little, I’d drag them in the backyard to watch the Perseid meteor showers.” They also brought the family golden retriever, April. “My dog is very confused as to why I’m lying out there,” Miller says. But as Miller lay there looking up at the shooting stars, he’d wonder about the identity of the stars, the age of the universe, the mysteries to be solved in the starlight. “Of all the creatures, only one looks this way into the night-time sky. To me that’s what makes the human being special.”

In the process, evolution’s popular defenders not only inflame religious conservatives, but alienate the public at large. “Increasingly I’ve been concerned that advocates of evolution are [the theory’s] own worst enemy in the public eye,” he says.

Defending evolution

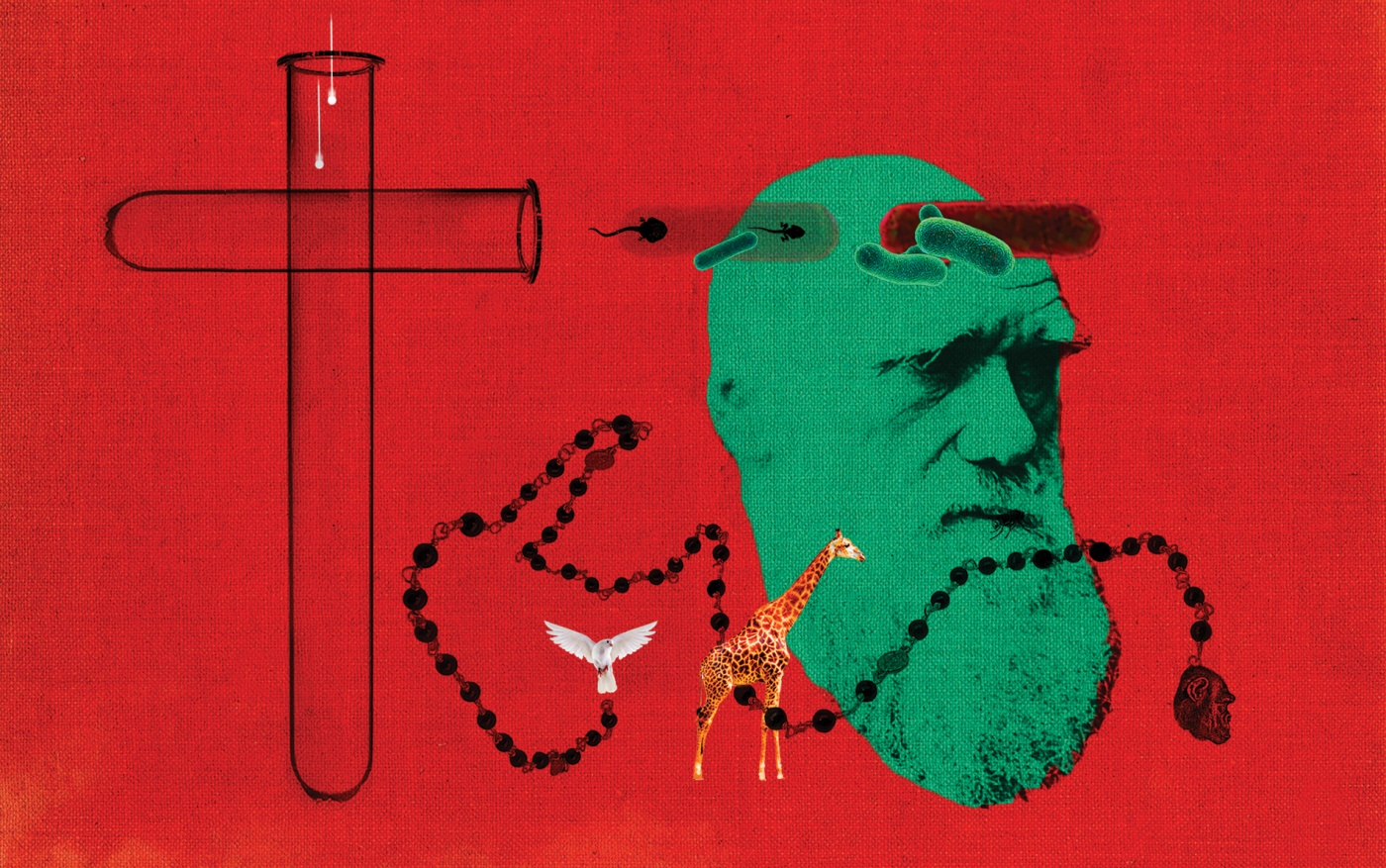

Miller is a working cell biologist, and when he isn’t teaching or publishing papers on cell membranes, he has served as one of evolution’s most visible public advocates himself. To defend the science of evolution from the pseudoscience of creationists, Miller, a practicing Roman Catholic, has written three popular books, including his latest. He has debated William Buckley and three anti-evolutionists on Firing Line; appeared many times on national television, and served as lead plaintiffs’ witness in Kitzmiller v. Dover, a pivotal Pennsylvania lawsuit that stopped a school district from teaching biology students intelligent design, a version of creationism.

Authors of popular books on evolution such as E.O. Wilson (Sociobiology), Richard Dawkins (The Selfish Gene), and Henry Gee (The Accidental Species) have made some solid points about human evolution, Miller says. For example, a Canadian study showed that a preschool child was 120 times as likely to be fatally beaten by a stepfather than by a genetic father, supporting the idea that biological fathers are evolutionarily driven to protect their kin. Other studies provide plausible evolutionary explanations for male sexual jealousy, female emotional jealousy, and our widespread fear of snakes.

In his new popular science book, The Human Instinct, Miller argues that while creationists are just plain unscientific, some of evolution’s most well-known advocates have also gone far astray. In their zeal to defend evolution, they’ve argued that the most inspiring human traits—our consciousness, our reason, our moral sensibility, our free will—are simple byproducts of Darwinian selection.

But many evolution defenders have dramatically overreached, Miller maintains. The Canadian study doesn’t mention, for example, that fatal child abuse by stepfathers is extremely rare, happening in just one in 2500 families—in the vast majority of cases, human values and ethics override animalistic instincts.

Humanity evolves

Ultimately, authors like Dawkins and Gee portray humans merely as products of their history, dating back eons to animal ancestors. In The Accidental Species, Gee, a former editor-in-chief of the journal Nature, argues that none of the signature traits of humanity—walking on hind legs, using tools, intelligence, language, sentience—are unique to our species. “The giraffe scientist would no doubt think the lengthening of the neck was the pinnacle of evolution, and any bacterium that wrote a book would view us as habitat,” Miller paraphrases.

What Gee is missing is that “there are no giraffe scientists and no bacteria that write books,” Miller says. “If we’re only the product of our evolution, it takes our species down a notch, dehumanizes us, and takes our independence away from us.”

The existence of the human spiritdoes not necessarily point to a divine designer, Miller believes, but it can’t be explained as the inevitable consequence of Darwinian selection, either. To bolster his point, he draws on insights from quantum physics—that the universe is inherently unpredictable—and modern neuroscience, which shows how the brain can spawn original thoughts and quickly and continually adapt. In other words, evolutionists have missed the “magic” that puts humans in a different category—and that science can still explain. Our brain is much more than an input-output device; our decisions are hardly determined by our evolutionary history. Instead, our brain is a unique organ that can generate independent thoughts, parse ethical distinctions, and make independent choices.

“We are the only species that is capable of looking out at the rest of the world, assessing it, and determining its place in it—and that alone makes the human species very, very special.”