The Cost of Skepticism

Scientists advance climate prediction models as the U.S. lags behind.

It’s been a hard year, I have to tell you,” J. Timmons Roberts said after returning from the UN Climate Change Conference held in Bonn last November. Roberts is the Ittleson Professor of Environmental Studies and director of the Climate and Development Lab (CDL). His conclusion? “Literally every country in the world is moving ahead [on reducing carbon emissions] without us.”

On the other hand, Roberts is pleased that in December, World Bank president Jim Yong Kim ’82 declared that the bank will no longer finance fossil fuel development. And with a lack of federal action on curbing carbon emissions, Roberts praises Massachusetts, California, and several other states for taking action to reduce them on their own. He says it might even be possible to meet the United States’ international obligations without federal leadership.

An expert in international climate finance policy, Roberts nevertheless emphasizes moral imperatives: because the West in general, and the United States in particular, has benefited most from fossil fuels, he says, they need “to show leadership and help developing countries cope,” aiding them financially to avoid an over reliance on fossil fuels.

Climate change will also increasingly influence another hot political issue: immigration. As sea levels rise and droughts get worse, people fleeing these conditions become refugees. “That’s already happening, destabilizing places around the world,” Roberts notes. Even U.S. Secretary of Defense James Mattis admitted as much during his confirmation hearing last year, when he told senators that “climate change is impacting stability in areas of the world where our troops are operating today.”

Having invested billions of dollars internationally on business and trading partners, the United States should protect its investments through climate action, Roberts insists. “Those decades of development are all at risk if they can no longer grow crops or their cities become uninhabitable.”

In the United States, Roberts says, “The impacts are going to cost trillions of dollars. It’s much cheaper to deal with the problem and much more expensive to deal with the impacts.”

Universities like Brown also have an important role, he says, in combating climate change denial: “I think that’s really where Brown can make a big difference. If we can’t speak up about this, then who’s going to?”

2 - THE NEXT GENERATION

Since 2010, Roberts has been training the next generation of climate activists by, among other things, taking them to international climate meetings. Last fall, he took 15 students to Bonn to observe how the 18,000 conference delegates attempted to hammer out ways to turn the broad 2015 Paris conference goals into specific actions.

Because the Trump administration has promised to abandon the international climate agreement in 2020 and has been quietly reversing rules banning oil and gas exploration on public lands and such little-known policies as removing consideration of greenhouse gas emissions from environmental reviews, the students did not expect the United States to be much help in Bonn.

“We went in with the understanding that the United States is no longer committed,” says Julianna Bradley ’17. Even if it were, she says, the Paris agreement alone cannot reverse the problem of global warming: “The Paris agreement is a big deal, but it is by no means a saving grace.”

Born the same year that the U.N. climate process began, Bradley became active on climate change after viewing An Inconvenient Truth, which features Al Gore and was directed by Davis Guggenheim ’86.

“The best way to address the fear and anxiety about climate change is to act on it,” she says. “Otherwise we’re just going to sit here, and the world is going to get hotter. If we don’t do something about it, as a generation, then it is going to even more deeply define us than it already has.”

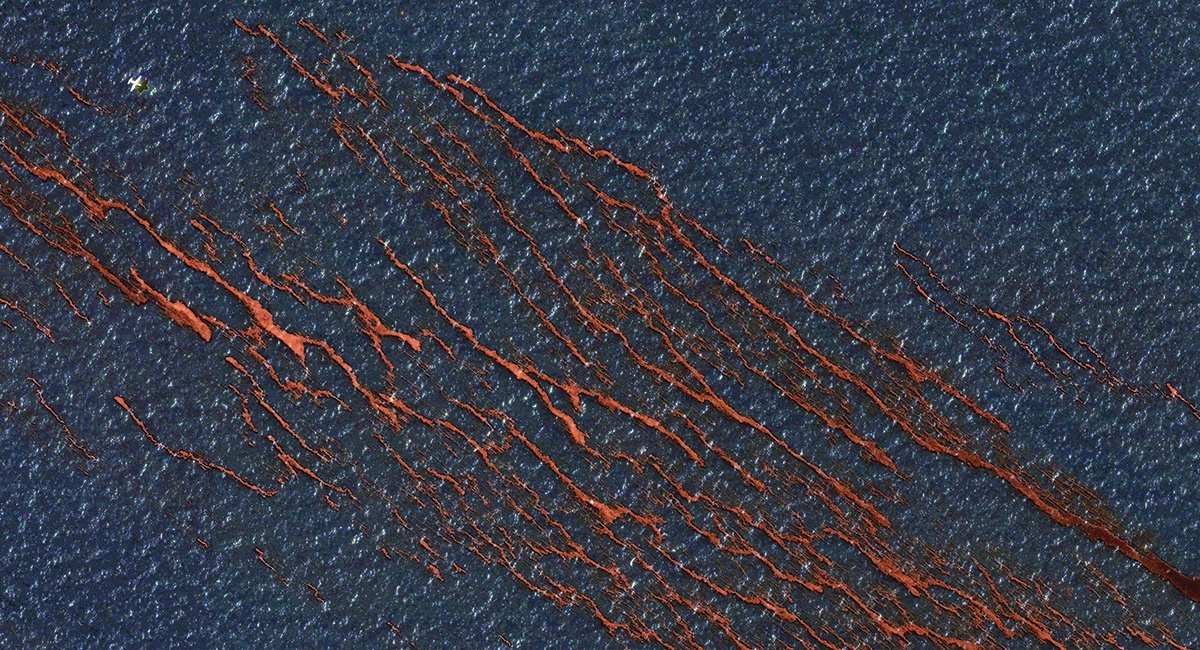

3 - LINES IN THE WATER

To model something as big as Earth’s climate, you have to understand the oceans. Baylor Fox-Kemper, an associate professor of earth, environmental, and planetary sciences, studies Langmuir circulation, a current that can have a significant impact on the ocean’s absorption of carbon emissions. When wind blows in a steady direction over open ocean water, running parallel to the wind are lines of foam made by long vortices of slowly rotating columns of water. The lines form because adjacent columns rotate in opposite directions, creating a signature of foam and debris on the surface.

For the last decade, Fox-Kemper has studied how this special wind-mixing affects the climate system. Air meets ocean at the boundary layer—the top layer of ocean, which absorbs such components from the atmosphere as energy, oxygen, CO2, and fresh water. A warmer climate means more wind and warmer water, which can accelerate the mixing of this top layer. “The rest of the ocean only knows about the boundary layer,” he explains. “Langmuir mixing makes that boundary layer deeper. That extra mixing really matters.”

About half the carbon dioxide produced from burning of fossil fuels ends up in the oceans. But whether it’s 40 percent of the CO2 or 60 percent has a lot to do with this boundary layer. Langmuir mixing connects the atmosphere to more of the ocean than we thought. “Exactly how much of the energy and momentum get taken out of the wind and put into the ocean depends on that boundary layer,” Fox-Kemper explains.

Plug all these insights back in to the latest climate models, and you’ll get a more accurate prediction of sea level rise. “It has practical consequences,” Fox-Kemper says. He is now using his work to improve the models of Narragansett Bay as part of a five-year National Science Foundation project with eight cooperating Rhode Island institutions.

“We know already that there are substantial environmental and climate change-driven challenges coming,” he says. “What can we do better to get from the global scale down to the scale that matters for local management decisions?”