Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas, Texas, is what’s known as a “safety net” hospital: an institution that accepts all patients, regardless of their ability to pay. Thus, the vast majority of the hospital’s patients are either on Medicaid or uninsured, and many are repeat visitors.

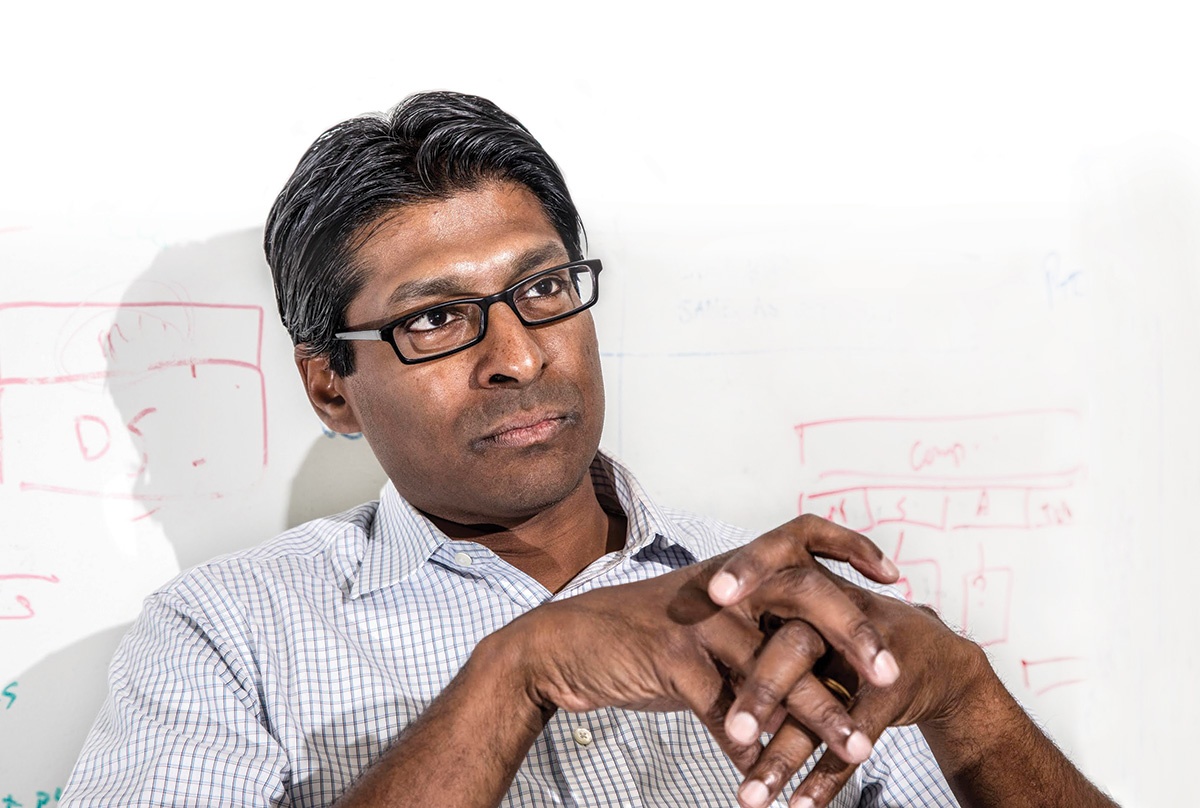

It was a 2011 hospital visit with one of these “frequent fliers”—a man with hypothyroidism who had been admitted six times in nine months—that eventually led Ruben Amarasingham ’95 to found Pieces Technologies, a start-up that aims to reshape health care in the United States.

A physician at Parkland, Amarasingham realized that his patient was homeless and semi-literate. Unable to procure the medication he needed—despite the fact that it cost less than a dollar a day—the man had been repeatedly hospitalized, racking up bills in the hundreds of thousands of dollars. So Amarasingham called the Salvation Army center where the patient had been staying and explained his condition. The man left, and didn’t return to Parkland.

“If there had been communication between the community organization and the hospital, this could have been avoided,” Amarasingham says. “I wondered, ‘Why can’t we, in this day and age, have better communication?’”

With a strong background in computer engineering, Amarasingham was primed to tackle the challenge. His solution? A computer network that would link medical centers and community organizations to treat high-risk patients more effectively. This software, dubbed Iris, became the centerpiece of the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation (PCCI) when it opened in 2015.

Iris’s initial results have been promising. Repeat visits to the hospital have, in some cases, been cut by two-thirds or more, resulting in an estimated $12 million in savings. This January, Amarasingham stepped down from his role as president and CEO of PCCI to devote himself entirely to Pieces Tech, which he launched in 2016. As the commercial arm of the Parkland initiative, the start-up is working to expand Iris’s reach beyond Dallas. It’s already begun crafting equivalent systems for cities in North Carolina, Kentucky, and Illinois.

“Good health is much more than good health care,” Amarasingham says, noting that research suggests up to 50 percent of clinical outcomes are determined by such nonclinical factors as dietary habits or unstable housing.

“My hope would be that every care plan for a patient would be able to address these social determinants,” he adds. “If that happens, I think we’ve really transformed the way that care is provided.”