Brown may not be the first place you’d go to major in studio art, but the basic design and drawing classes I took just for fun my sophomore year challenged me on a gut level that academics never had. I was hooked. After a junior year in France, I had only one year to develop what would become my profession and passion. Professor of Visual Art Walter Feldman, who died May 20 at 92, guided me onto that path, with down-to-earth instruction and unwavering commitment.

Short, stocky, and gravel-voiced, Feldman embodied an approach rooted in a tactile love of materials and what they can teach. Today I never wash a brush without remembering the humility and dignity he imparted to this otherwise tedious task. And his is the voice I hear when my work is in need of revision.

Feldman’s art was shown internationally and received awards from such places as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and Milan’s Mostra Internazionale. Yet he didn’t want his work confined to museums and galleries. His art was also put to use on campus, where he designed everything from a medal for exceptional engineering alumni to a sculptural “Keep Off the Grass” sign at Wriston Quad. For decades before the digital age he created art to illustrate the course catalog.

Feldman worked in paint, wood, stained glass, mosaic, silver. He made prints and bound books by hand. His yearlong Art of the Book workshop was famous, and when he retired in 2007 Brown opened the John Hay Library’s Walter Feldman Book Arts Studio, which contained more than 300 books made by his students.

Feldman presented art as a profoundly human struggle, a battle never won but always worth fighting. As both a decorated veteran of World War II—he limped from a serious injury he’d suffered during 1945’s Battle of the Bulge—and as a Jew, his wartime experiences and the horror of the Holocaust were never far from his mind. This lent a gravity to his perspective that moved me. As graduation neared and my anxiety about the future built, he sensed my distress and invited me out for coffee. The advice he gave me, proffered with kindness, was, “Never stop being critical of your work.”

Feldman’s characteristic sweetness and grit helped students find their way, whether it took them toward or away from the arts. Todd Cymrot ’96 remembers that he was so impressed by Feldman’s cover design for his freshman-year course catalog that it helped prompt his eventual decision to abandon his premed concentration. When Cymrot told him he was premed, Feldman exclaimed, “Why the fuck would you go and do a thing like that?” It was, Cymrot remembers, “his salty and spot-on response.” Feldman had noticed “I was way more animated when talking about other things—art, book making, my thesis—than I ever was about being premed.” Cymrot went on to get a master’s in teaching from Stanford. “He also let me know, kindly, that I was a terrible artist. So that’s two career paths narrowly avoided due to Walter Feldman.”

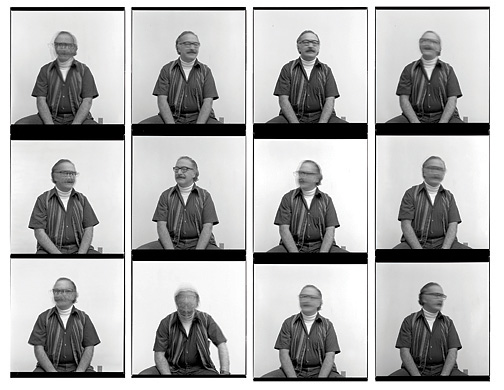

The professor wasn’t one to mince words. Feldman posed as a model for a drawing class Jill Rucker Simmons ’76 took the fall of her senior year, then he critiqued the students’ work. “When he approached my station,” Simmons says, “he stood still for a minute as he viewed my drawing, then said to me, ‘Fatter, but thank you.’”

Paul Cormier, a senior library associate, took a Feldman class in 1987 and says the professor expected a lot of art concentrators. He remembers Feldman asking one unfortunate art major about her final piece: “Where’s the rest of it?” Cormier uses that quote to this day, he says, when something falls short of its mark.

The gruffness often covered warmth.“Walter’s face would light up in a smile every time he met someone,” Cormier says. And he could be very supportive. David Goldsmith ’88, a self-described “rudderless math concentrator,” says that when he drifted into Feldman’s printmaking class he received encouragement, an invitation to Feldman’s home, and a gift of an etched carving tool—despite Goldsmith’s slow output and uneven work quality.

Virginia Coley Gregg ’58, a biology major, witnessed the teacher’s curiosity. During his introduction to studio arts course, she asked him if an assignment to draw something inspired by nature could include the “nature” she saw under a microscope. “Mr. Feldman looked at me and asked, ‘What do you see under a microscope?’By the time I had collected some slides to give him, he had already gotten permission to take an old microscope to his studio and learned to use it,” she says. Next thing she knew, he’d painted a mural in a biology department stairwell based on what he’d seen.

When Feldman joined the faculty in 1953, he was Brown’s only studio art professor, and all his students were Pembrokers.The combat veteran visited fraternities, challenging the men to take his class, telling them that “you really had to know yourself to be able to do art.”

After retiring he kept painting. He also designed, illustrated, and printed books for his imprint, Ziggurat Press, which he’d founded in 1985. In March 2016, at almost 91, he showed eighteen wartime-inspired paintings at the Providence Art Club. “Even though it is too painful to talk about some of this, I think I got there in the paintings,” he was quoted as saying in the Providence Journal. In August, to Feldman’s four battle stars, Purple Heart, and combat infantry badge, Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse added a posthumous Bronze Star. “I always thought I married an artist,” Barbara Feldman, his wife of nearly 67 years, told Whitehouse. “But I’m just finding out that I married a war hero too.”

I kept up with Feldman over the years and visited several times, arriving late once, impromptu, to a lecture he was giving on his book art at the RISD Museum. He hadn’t seen me in more than ten years, but his face lit up and he stopped in mid-sentence to say, “A former student just walked in!”

Ten years after graduation, when a friend was hired to teach art history at Brown, I asked her how she liked my beloved Walter. Her diplomatic reply was, “I think Walter gives the best of himself to his students.” Undoubtedly true—and we are grateful.

Colette Crutcher is a San Francisco painter, ceramist, and mosaic artist.