In the summer of 1987, the black sand of a seedy Tyrrhenian public beach in the Italian town of Ladispoli was my open-air reading room. My parents and I had left Moscow after almost nine years of refuseniks’ limbo, and we were spending the summer in Italy, waiting for our U.S. refugee visas to be processed. In preparation for coming to America, I pored over books by Russian exiles. First on my list was Vladimir Nabokov, who remade himself after coming to America as a refugee in 1940, having rescued his Jewish wife and son. Would I ever be able to write in another language? I wondered that summer. What would be the price of losing my Russian voice?

Silver-haired, witty, verbally perverse, Hawkes listened to my rambling account of leaving Moscow, writing poetry and fiction in Russian, and coming to the United States. He waited, silently, lips twitching, then asked: “Have you read Nabokov?”

Hawkes pronounced the second “o” in Nabokov’s name with an extra roundness.

“Nabokov?” I asked, in disbelief. “Of course I have.”

“He’s remarkable,” said Hawkes.

Even though Hawkes had no interest in Soviet politics, no ear for Jewish immigrant anxieties, he let me into the seminar. So in the spring of 1988, a translingual novice surrounded by other young writers—all of them American-born—I tried my hand at composing in English.

I’ve now lived in Boston longer than in my native Moscow. Over the years in America, I’ve written in both English and Russian, sometimes simultaneously, sometimes not. I’ve often wondered what this means for my identity as a writer.

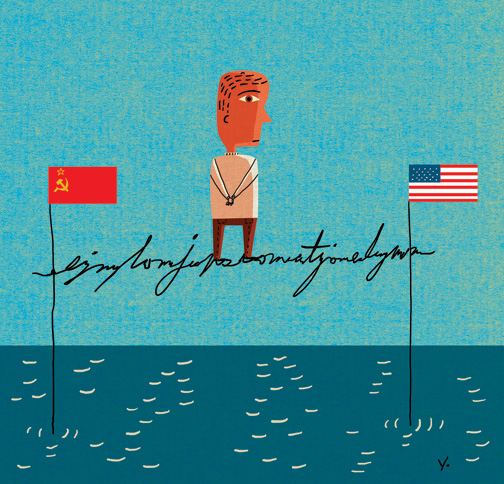

In the not so recent past translingual writers were all alone, artistically homeless, culturally stateless. Think of Paul Celan, a multilingual Jew from Northern Bukovina who lost his family during the Shoah, went on to write and publish peerless German-language poetry, and in 1970 killed himself in Paris. Writing translingually can leave one betwixt and between. But what happens when writing across culture and language becomes a literary movement, as has happened in recent decades?

Let me turn to the story I know best, that of ex-Russians—and ex-Soviets—writing in English. Nabokov had very few colleagues when he arrived in America from France in 1940. But in the 1970s and 1980s, many more writers came to the United States and Canada from the U.S.S.R., many of them children and young people, riding the wave of the great Jewish emigration. They have literary great-uncles and great-aunts on both sides of the Atlantic.

In addition to plenty of role models, representatives of this new wave of American and Canadian translingualism also have lovers and partners, friends and next-door neighbors, who work in both languages. It’s almost become a Russian-American family business, and also something of a Jewish community affair. Will being a part of this new translingual community cause us to modulate our unique literary voices?

Only time will tell. Thirty years after taking John Hawkes’s fiction workshop—and feeling like a stranger among my American peers—I’m still discovering the hidden pleasures of writing in tongues.