In 1969, my parents bought a rather grand high-fidelity stereo system for the living room in our house in the Connecticut suburbs. It was funereal, stately, ostentatious, and occupied the better part of one corner of the room. The housing, which secreted away the stereo components, consisted of some elegant finished hardwood, within which was inlaid a turntable, and a tuner, and a shelf on which to store some portion of your LP collection, and two speakers, at either end. All dolled up in the cabinet. The Joneses must have had one and we were keeping up.

Mostly, the coffin-sized stereo got played right before dinner. My mother liked to put on music while laboring domestically in the kitchen, and I liked to sit around in the living room preoccupied with whatever was on. My mother’s most fervently listened-to albums were by Simon and Garfunkel. We had their every release, and I can remember deep engagement with “Bridge over Troubled Water,” which still causes the hair on the back of my neck to stand up.

And then there were the Beatles.

I heard them on the radio practically from my first culturally aware moment. I can remember “A Hard Day’s Night” (and that F9 chord) not long after its release, and “Eight Days a Week.” “Help!” might have been the first Beatles single I contemplated as it was happening, and maybe this is indicative. I knew “Yesterday” and “Michelle,” likewise. But it wasn’t until the single releases in the span of Sgt. Pepper that I had a grip on the hysteria of the Fabs—who the artists were, what they looked like, their apostolic names. Magical Mystery Tour, and its related effluvia, was on heavy rotation on a small close-and-play upstairs in my bedroom, even though those songs were strange, and thereafter I was hooked. There was ample material to catch up with, and then there was the new stuff coming out. The White Album! Let It Be!

I don’t know what prompted my mother to acquire Abbey Road, because she wasn’t as fully committed to the Beatles as were her children. In a way, it’s a measure of how demographically immense the Beatles’ popularity was. The “granny tracks” that John Lennon so uncharitably (in the solo-era Playboy interview) disparaged among Paul McCartney’s compositions lured in the likes of my mother and father. My mother was interested in the popular song only when it was very literate or musically sophisticated. Therefore, it must have been some single from Abbey Road that was much in evidence. Let’s say it was “Something” by George Harrison, for example, which was a justifiably celebrated single from that album, with its swells of romantic feeling. (I considered myself a partisan of George above all other Beatles in those days, and I still feel awed by his unusual set of gifts—his love of augmented and diminished chords, his feel for Indian classical music, his melodic lead parts, etc.)

Whatever the cause, my mother bought Abbey Road, and soon it was playing on the high-fidelity stereo system with great regularity during the dinner hour. I liked to dance to it. So did my sister and my brother and my mother. I can recollect, for example, dancing to “Come Together,” which, while not exactly James Brown, is plenty danceable if you are eight or nine years old and just like any song that features a drum kit. I had no idea about the double entendre in the chorus.

My parents’ marriage was dissolving at the time. That’s the portion of the story that serves as the backdrop to this suite of songs that I’m about to describe.

I didn’t know it was happening, not exactly. It is the fate of the child to adapt to the circumstances on the ground. Whether it’s sheep-herding on the Mongolian steppe, or rock-throwing in Palestine, or marital disaffiliation in the Connecticut suburbs in the early seventies, the child adapts. I knew that my parents didn’t have very much to do with each other. I rarely saw them in the same room, and, when I did, they didn’t exactly embarrass themselves with a surfeit of affection. The arguments were few and far between, but so was the kindness. I cannot remember ever seeing my parents kiss. I assumed, as was perhaps not infrequent in the upper-middle-class enclave where we lived, that this was just how people were. I often had my nose in a book, or was camped out in front of the television, and I didn’t consciously attend to any nearby drama that did not impress itself upon me.

The evening came when my mother sat all three of us kids down to tell us something important, and, though there is much that I have forgotten from that time in the Connecticut suburbs, I can remember a lot about this moment—my mother’s lipstick, my brother weeping and saying, “You aren’t going to get divorced, are you?” before she had even finished her declaration. We were sitting in front of the fireplace in the den. It must have been a significantly uncomfortable moment for my mother, who was leaving my father, to attempt to explain her decision, and now I can feel it, that woe and misery and remorse, which I didn’t feel then. My perception, while sitting there by the fireplace with her in the den, was of resignation. My feeling was that there was nothing I could do about it. My feeling was that I was about to be an item on an itemized list of marital property. My brother wept.

Here’s what I have often found in my moments of keenest disconsolation: that music has an unexpected power to console and to transmute what is most grievous. The layers of imperviousness that smother a song when you listen to it a lot, these layers are sundered away, and music is apparent in its most elemental guise, full of mystery and passion and awe. Things that you haven’t heard in a fresh way in a thousand listens are suddenly bright and new, when you really need them most.

And so it was with Abbey Road.

One night, after the sit-down, my parents enclosed themselves in the living room at our house, in a way they had never done before, and it was in this conversation, it seems to me, that they negotiated the sundering of their union, without any of us present. There were louvered doors in the living room, which space, as I have said, also featured the hi-fi and the piano, and on this night the louvered doors were closed. I don’t know what was said exactly, but I noticed, from upstairs, by peering down the staircase, that these metaphorically rich doors were closed, and I suspected that an end was near.

It’s not that Abbey Road was playing that night. It’s that through some metonymic action, in which a work of art becomes a symbol of all that is adjacent, Abbey Road, with its bright, glorious production, its elegant string arrangements, its strange and elevated moments, its harpsichord and Moog synthesizer, has become the sound, for me, of my parents separating. And, in particular, one passage on Abbey Road, when I think back now, inevitably suggests the grief about my family as no other artwork does. It’s the passage that begins with the song “Golden Slumbers.”

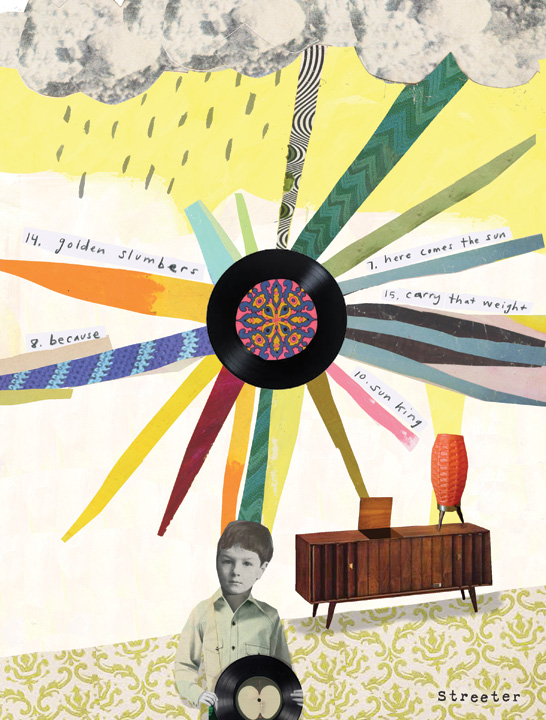

John is alleged to have hated the “medley side” of Abbey Road, which was the conceptual work of Paul and George Martin. I remember my mother explaining how the songs flowed from one to the other in the medley, and my epiphanic recognition of this was first located in the fact that the theme from “You Never Give Me Your Money” turns up much later in the medley (in “Carry That Weight”). (I was also fascinated that George’s “Here Comes the Sun” echoed John’s “Sun King.”) The Abbey Road medley was a gorgeous, playful, sophisticated expanse of fragments, urgent and propulsive. As others have suggested, the medley was much preoccupied with the Beatles’ own dissolution, in a way that was dark and regretful—at least until the passage entitled “Golden Slumbers.”

It’s a lullaby! A lullaby that spontaneously appears after “Polythene Pam” and “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window.” And it’s because it’s a lullaby that it was so powerful for an eight-year-old in a confused, resigned state. A song to soothe and mollify. And it’s a particularly ancient lullaby, moreover, when you consider that the original poem on which it is based, by Thomas Dekker, was written in the early seventeenth century:

Sometimes the oldest art has the greatest power to summon the uncanny, and maybe this was what impressed Paul McCartney, expectant father, at the sessions in question, the eternal agape of parental concern. Mary McCartney was to be born right after the sessions for Abbey Road, and no doubt his performance reflects this. Paul, as recorded, was the father who cared about the welfare of the kids in “Golden Slumbers,” who lingered over the children of his domain, and it was the tenderness, the generosity, of McCartney’s performance (and his summoning of the idea of home in the section of the lyric that he added to Dekker’s original) that somehow had such an impact on me, that made me envious, that made me aware of what I wanted that I didn’t even know I wanted, upstairs, gazing down, the idea of home.

Still, if you linger over the perfect tenderness of “Golden Slumbers,” the paternal generosity of it, as with many fleeting moments in the Abbey Road medley, you miss what happens next, which is “Carry That Weight.” With a considerably evident Ringo belting in the chorus. It would be a lie if I didn’t think, as one does in troubled moments, that the idea of a burden being carried by a “boy” seemed, in 1970, wholly directed at me. No one else could know as I knew about carrying that weight! I took on that line from “Carry That Weight,” which is the only striking bit of lyric-writing in the song, excepting the brief calling forth of an additional “You Never Give Me Your Money” verse. (Yes, one could develop an argument about “You Never Give Me Your Money” and divorce, but that would be to accord a ligamentary passage in the medley more space than it had in the original recording.) “Carry That Weight” does not endure much beyond 1:37, but it lingers as an afterimage in what follows.

The medley would not have crafted its legacy, that is to say, if it didn’t land well. It would be a collection of diverse and unfinished investigations, as John Lennon worried it would be, if it didn’t end dramatically. If it didn’t come down with emphasis, in a commentary on what the Beatles were up to at that time. And as befits the unparalleled achievement that is Abbey Road, the medley comes down, therefore, on “The End.”

Beatles in their adulthood, battle-scarred from internal struggle, had become, as adults do, exceedingly good writers of searching and reflective ballads (see “Golden Slumbers,” above, or “Let It Be,” or “Across the Universe”), of the meditative, and the melancholy, of the complex. But they were, at the moment of their origin, a really great rock-and-roll band. Scrappy, loud, and sexy. And the moments on Abbey Road, like “Oh! Darling” and “Come Together” and “I Want You (She’s So Heavy),” when the band trafficked in that idiom of rock and roll, are indelible moments, important moments, some of the most important moments in all of rock and roll. For me, none of these passages exceeds the compacted and cumulative power of “The End.”

There’s a little intro section, a mere smattering of words, and an upwardly ascending guitar figure. Oh yeah! All right! Played through just once, it invokes the dream register, desire and nightfall, after which “The End” (and the medley, generally) immediately does what it needed to do: it improbably yields to a Ringo Starr drum solo. As if proving that rock and roll is first of all a thing that requires drums. All toms! Not even a glancing cymbal in the solo, nor hi-hat, just those toms, spread wide in the stereo signal (it sounded incredibly great in the living room, when you turned the hi-fi up loud). So rare are the drum solos on rock and roll studio albums that they have an especial intensity when they do come to pass. Ringo, it is said, especially resisted solos. This one was crafted from an ensemble instrumental passage, from which everything else was stripped out. It is blunt, simple, and incredibly forceful.

But even the drum solo is not the final word on “The End.” The song, as an ending, has to end even more dramatically than it might have done here. So: first Ringo falls back into his backbeat, his groove, and then bass and rhythm guitar enter, on the I–IV, of course. A7 to D7, if you want to be specific (there’s a whole argument about how the medley is in A when it’s about “greed” and in C when it’s about the triumph over greed), and that’s when something additionally important happens, perhaps something more than important.

What is it about the I–IV chord progression that’s so lasting? Well, it’s modal, yes, so you never have to leave the home key, and you can drone as much as you want, which is why Lou Reed liked it so much (on, for example, “I’m Waiting for the Man” and “Heroin”), and it’s easy to learn on the guitar (especially if the song is in E: see, for example, “Gloria”), and it somehow permits all the old folk melodies. It has been used in every era of the popular song. In this case, it’s as if the Beatles are going back over the entirety of their career, finding what is the lowest common denominator of everything they ever played together, at the Cavern Club, in Hamburg, at Shea, in all those studios, and up on the roof, the I–IV. If you were to try to describe, to some sequestered person, raised on the fabled desert isle, who had never heard rock and roll, what it was, and why it saves lives, you might begin by trying to describe melodically the I–IV. You might say that it’s the minimum of melodic development to still qualify as development, rock and roll style. And so: this is where Paul situated his climactic moment of the medley, right here on the I–IV, and it’s like those moments on Van Morrison albums when you can hear Van shout to the band behind him, One four! which means Play on. As with Al Green’s church revivals, when he just wants to feel the word of God, when he wants to let go and testify, and he looks at the band, and they know it’s I–IV. This part of “The End,” which some people describe as the last moment when all the four Beatles recorded together in a studio, is like that, it’s like the word of God, if the word of God were a thing explicable only in guitar, bass, and drums, the most infernal racket that is the most divine racket.

And let me say something about the seventh chord. That flatted seventh is so Beatles. Most I–IV progressions, like when Lou Reed played them, avoid the flatted seventh, but to play the “accidental” seventh with the gusto that the Beatles played it (there are lots of these sevenths in the Revolver period) is to summon up the tradition of the blues, and soul music, and black music generally, and to make that gesture part of the ending on “The End” is to remember the role that black music played in who the Beatles were: commentators on the whole expanse of the popular song, and even beyond. Not capable of being confined by British popular music, or psychedelia, or Baroque music, or Indian music, or anything else, but magpies, claiming whatever shiny thing seized them, and refining and repurposing it.

Here is the I–IV as if it were written on a scroll, or on parchment, over which the Horsemen of the Apocalypse ride in, the tripartite guitar solo section. The infamous Paul-George-John guitar showdown at the end of a long and winding career.

It is fair to say that there was not a perfectly proficient improviser in the band, remarkable though they were. Paul was probably the best instrumentalist in the Beatles, but he was most effective on the bass. George was an exceptionally beautiful lead guitar player, as I have said, but more as a composer of melodies on guitar, more as a microtonal note bender and slide player, than as a guy who could just whip off a great solo. The most technically accomplished guitar solo on any Beatles album is perhaps Clapton’s solo on “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” George would never have written a part like that. He wrote out his parts for the songs to adorn the songs, not for the display of virtuosity, and he perfected them, labored over them, like a great composer. And that’s why his parts are so sublime. (Compare, for example, the two extant solos on “Let It Be.” Two completely lucidly thought-out solos. And utterly different.)

And John was no kind of guitar player at all. John was an unsurpassed writer, and an incredible singer. A singer of richness and singularity and emotive power. But he was not a guitar player of much note. Nevertheless, they were going to do this thing, these three men, and they were going to do it in a really inventive way: by playing two bars of a solo each, in rapid succession—Paul, then George, then John. Two bars! An abbreviated space! The solos are astoundingly good, and if you go online and watch all the many, many times that Paul McCartney has reconstituted live this particular passage of music in the decades since, you will learn, inferentially, how great the recorded solos are, because no matter how road-tested Paul’s band is now, and no matter how spectacular are his guest players (e.g., Dave Grohl), he cannot best the performance of the three internally feuding Beatles. Paul is all spiky and sharp on the recording, like he was in the mid-sixties, while George is given to improbable melodic leaps of huge intervals, like a slide player, and John is a rhythm guitar noise factory. They only have the two bars to develop each musical thought, and they develop them quickly, with great mastery, in the context of the group. They develop the ideas together.

To me, almost no moment in rock music is more epiphanic, more shamanic, and more transporting than this little piece of the medley. It’s a demonstration of what rock and roll is, and it derives rock and roll, like rock and roll is a mathematical theorem. And then, after the tremendous noise assault of John’s last two bars, a swooping string section and piano part come in, the whole thing swerves back into George Martin–style chamber pop, and Paul reduces down the medley and the album and the decade of the sixties and the oeuvre of the Beatles to one essential equation about the nature of love: what you take = what you make. All the entire career of the Beatles, all those love songs, all those experiments, boiled down to the equation.

What did the equation mean to a kid in the suburbs, the equation of that last line of “The End”? It was a comparable gesture to “All You Need Is Love,” which I also thought was exceedingly deep. “The End” and its equation attempted to demonstrate that the whole troubadour history of the popular song, in which the eminences of song were strolling minstrels singing under the windows of particularly fetching noblewomen, for example, could be restated in a few simple ways. Love, as transitive verb, or perhaps as philosopher’s stone, was passed from hand to hand. Love, the equation remarks, is a restatement of the Golden Rule, the Golden Rule as some universal constant, and it makes clear that the goal of life is to total up evenly, and to recognize that that evenness, the ultimate serenity of love, constitutes a kind of moral vision. Perhaps, to me, sitting at the top of the stairs, watching the louvered doors of the living room, beyond which there was the hi-fi, the equation made clear, even in a down moment, that at some point the whole depletion of love and warmth and loyalty and common purpose was going to balance out. That could be relied on. No matter how harrowing the moment, things would get better.

If you think of the songs that the Beatles wrote on Abbey Road about how hard it was to be a Beatle at that time (George’s “Here Comes the Sun,” Ringo’s “Octopus’s Garden,” Paul’s “You Never Give Me Your Money”), it’s nonetheless possible to see the equation of “The End” as yet another example of the yearning for something better that those four guys managed exceedingly well when they were at their very best. And that’s part of why “The End” feels so sublime, when it winds up into the sinewy George Harrison solo that closes it (in the company of some winds and some horns); even in the midst of bitterness and distrust, there is, nonetheless, a bounty of hope.

The dream was over. Even, in the coming days, while dancing around to a brand-new high-fidelity stereo system in the coffin-sized pine box, during the coming-to-the-end of family, before all the moving around, and changing schools, and losing my friends, I could sense that the dream was over. And yet, when the music came on, there was the bounty of hope.

From In Their Lives: Great Writers on Great Beatles Songs, edited by Andrew Blauner ’86 (Blue Rider Press/Penguin Random House). Used with permission of the author.