Peter Andreas sits talking about his mother at a table in his third-floor office at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs. Behind him, a large window overlooks Thayer Street and lower Wriston Quadrangle, and floor-to-ceiling bookshelves line the side walls. One shelf holds copies of the ten academic books he has authored and coauthored, including Smuggler Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America, which was selected by Foreign Affairs as one of the best books of 2013.

An Ivy League PhD, a named professorship at an Ivy League university—you might think that Andreas’s childhood education was equally prestigious and tweedy. For three decades that’s what most of his colleagues and students probably thought. “I had long kept most of the details of my childhood to myself,” he says. “It wasn’t a secret, but I felt talking about it would generate questions. It isn’t something you can explain in a few minutes of casual conversation.”

Then, in December 2004, his seventy-one-year-old mother, Carol Andreas, died suddenly of a cerebral aneurysm in her Colorado bed. “It was the most devastating moment of my life,” Andreas says.

In her house he found “boxes full of diaries – more than 100 notebooks that covered three decades.” He brought them back to Providence and spent winter break reading them backwards chronologically. “It was part of my mourning process,” he says. And his childhood came flooding back.

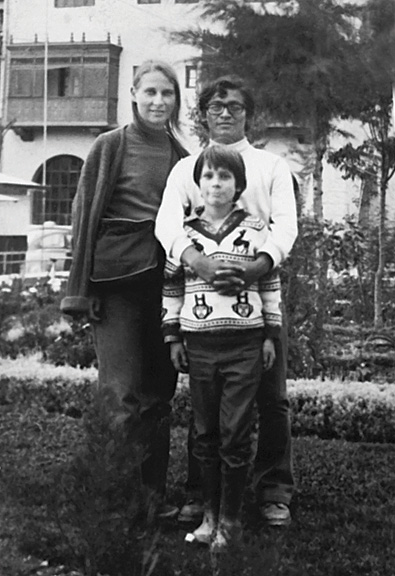

As a boy, Andreas had been kidnapped by one or the other of his divorced parents three times, moving between a conventional suburban life with his father and a nomadic, rootless existence with his mother, a political activist who spent most of her adult life wandering South America in search of one revolution or another. While his father, during their infrequent times living together, kept him in school, focused on going to college, his mother would swoop in and take him away. For decades, Andreas was torn between love for his impossible mother and a need for the reassuring stability of his father, all the while trying to figure out who he was and what he wanted his life to be.

The Andreas family turmoil began during the 1960s, when Carol, a graduate student at the time, became increasingly radicalized and eventually filed for divorce from her more conservative husband, Carl. Drawn to the idea of a revolution that would free “the people” from oppression, she resolved to go in search of it by abducting Peter—who was five years old and living with his father in Detroit at the time—and fleeing to California. Gone were TV, clean sheets, and a parent who returned home every evening at the same hour, replaced by life in a Berkeley commune that hung a Vietcong flag from one of its windows. But Berkeley wasn’t enough for Carol. After a few years there she dragged Peter with her to South America, an incendiary battleground of social change, and began a four-year period of life on the road.

“Long before her death,” Peter Andreas says, “I had in the back of my mind that I should write something about my childhood, maybe an article. When I found the diaries I realized I had a treasure trove of research material.” Reading his mother’s the diaries, he says, “helped jar my memories of those years.”

“Some would say my upbringing was tumultuous or neglectful,” he adds. “My mother was arguably negligent, but I never felt neglected.”

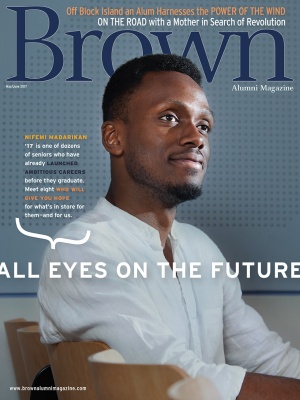

In April, Simon and Schuster published Rebel Mother: My Childhood Chasing the Revolution, Andreas’s attempt to make sense of his childhood. In a scholar’s measured voice, he describes his picaresque and sometimes harrowing journey as a young boy wandering through the hectic political landscape of the 1970s. At its center is Carol Andreas, and although his mother’s obsession with “the rebellion” at the expense of hands-on mothering may seem irresponsible, the book is as much a love story as it is an unorthodox adventure.

In the late 1950s Carl took a four-year government-funded job running a medical school program in Karachi, Pakistan. Carol, intrigued by the local culture, couldn’t help but notice the contrast between Karachi’s poverty and the comfortable bubble that encased the expatriate community.

Back in the United States, the family settled in Detroit, where Carl took a job as benefits manager for the United Auto Workers. Carol enrolled in a PhD program in sociology at Wayne State University and discovered the works of Marx, Engels, and other seminal leftists. She was writing her dissertation when Peter was conceived, a development that she later told him was a mistake, but a happy one.

Carol and Carl had demonstrated against the Vietnam War, but Carol went further. She rooted against the U.S.-supported South Vietnamese government and for North Vietnam’s communist regime—“heroic anti-imperialists,” she called them. While teaching college classes part-time, she joined People Against Racism, which was aligned with the Black Panthers. She founded a left-wing academic journal, The Insurgent Sociologist, and wrote a book, Sex and Caste in America, the first of four she would go on to write over the years.

As a leader of the Michigan Women’s Liberation Coalition, she made headlines by keeping male reporters out of a press conference. Her sons, however, were welcome at the revolution. “I went to my first antiwar demonstration before I was eating solid foods,” Peter writes in Rebel Mother. “At age three, I rode a ‘flower power’ tricycle sporting a peace sign in a parade.”

The disconnect between her radical convictions and the more conventional liberal politics of her husband, Carl, prompted Carol to file for divorce in 1969. When Carl came home one day and found her belongings gone, he acted quickly to pick Peter up from preschool before Carol could take him—the first abduction. “That afternoon is my first memory,” Andreas writes. “The war over me was just getting started.”

The older boys chose to live with Carol during the year and a half until the divorce hearing was scheduled in November 1970. To Carol’s shock, the judge refused to grant her the divorce. That same month she took Peter from his kindergarten and within days fled with him, Joel, and Ronald to California, where she created a commune in a big old Berkeley house. Thanks to California’s more liberal laws, Carol succeeded in getting a divorce and custody of all three boys.

In early 1972, several years after arriving in Berkeley, Carol decided she could better serve the Marxist cause in South America. “My mother had less and less patience for feel-good American bourgeois liberalism,” Andreas writes in Rebel Mother. As they prepared to move, Carol told her seven-year-old son, “We’re going to be part of a revolution. It will be the biggest adventure of your life.”

Joel, in his mid-teens, opted to stay in Berkeley, while middle son Ronald accompanied Carol and Peter but immediately left to hitchhike the continent alone. In Guayaquil, Ecuador, Carol rented a bug-infested house next to a sewage-filled river, proudly describing the environs as “one of the largest slums in South America.” She began reading and doing field research in preparation for writing a book on the role of women in the Chilean leftist uprising.

Peter, meanwhile, was left to explore on his own. Shortly after their arrival, he wandered away from the house in search of ice cream and became lost in a maze of city streets. He had no idea of his new address. Eventually a helpful man drove Peter around in a pickup truck until he recognized his house. “Next time you wander off,” said Carol, “don’t forget our address again.”

Carol’s work took them to Chile, Argentina, and Peru. They stayed in rundown hotels, apartments, and squatters’ shacks, where Carol bedded a succession of young lovers, often in the room she shared with Peter. Sometimes their only plumbing was a hole in the yard. Rats ran freely indoors, and fleas swarmed on their beds at night. Peter sporadically attended local schools, but he didn’t learn to read until he was eight.

Mother and son shared a house in Santiago with political exiles drawn to Chile by the leftist presidency of Salvador Allende. “It felt like we were part of something important,” Andreas writes in Rebel Mother. “I started to mimic my mother, talking constantly about being for ‘the people,’ ‘the masses,’ ‘the working class,’ and being against ‘the system,’ ‘the ruling class,’ the dominant elite,’ ‘the bourgeoisie,’ and the ‘capitalists’ and ‘imperialists.’” His anti-establishment habits died hard: back in the United States years later, when his tenth-grade teacher announced that President Reagan had been shot, Peter reflexively raised his fist and shouted “YES!”

While Peter was generally unfazed by his chaotic life on the road, Carol often underestimated how much her young son needed her. In the book he relates that for several months in 1973 she left him in the care of cooperative farmers in rural Chile. Peter happily tagged along with an older boy on the farm, learning how to weed bean fields and tend animals, while Carol worked on her book in Santiago.

On September 11, his idyll was interrupted by a broadcast on the farm’s kitchen radio: a right-wing military coup in Santiago had toppled Allende’s government. For several weeks Peter heard nothing from Carol, and he became agitated. “How could my mother have left me there by myself?” he writes. “How could she care more about her book than about me?” Carol eventually returned, but with Chilean soldiers searching for Allende sympathizers she knew it was time to move on. For a year the two traveled to Argentina and a number of cities and towns in Peru.

Then, in December 1974 they returned to the United States so Peter’s parents could finalize their property settlement—contingent on a custody ruling. To Carol’s horror, the judge awarded custody of Peter to Carl and his new wife, Rosalind. In August 1975, Peter left his mother’s vagabond life to move into his father’s comfortable home, where he thrived on the couple’s attention. Carol feared her son was in danger of being co-opted by mainstream American values. She sent him urgent letters, writing in Spanish so his father couldn’t read them, about her plans to free him and return to Peru. The resulting emotional tug-of-war still stings when Andreas talks about it today.

“Out of my entire childhood, that was the most torturous moment—having to choose between my parents,” Andreas says. “I knew if I didn’t go with my mother, I would not only risk losing her affection but also explicitly reject the class struggle and be a spoiled sellout.”

Overwhelmed by Carol’s pressure, and believing she needed him more than his father did, Peter allowed her to abduct him from school one more time. “By choosing to leave, I had to be complicit in breaking the law, fleeing over the border, and not seeing my father for years,” he says.

The two escaped to Peru and lived with Carol’s young street-performer husband, Raul, and his family. Sleeping on straw mats and using newspaper for toilet paper, Peter continued to feel pulled between two worlds. “I intensely missed my flea-free bed, Saturday morning cartoons, and Frosted Flakes,” he writes.

Raul and Carol fought continuously, and she gave up on the marriage. In the summer of 1976 she and Peter left South America for good. They made their home in Denver, not far from Carol’s parents’ home in Kansas, for the next seven years—the longest Peter had ever lived anywhere.

In Colorado, Peter, now eleven, was free to be an American boy again. He lagged behind his age group at school but learned quickly. Thanks to a tiny television set Carol bought for their apartment, he put aside the futbol he had played in South American streets and began to root for the Denver Broncos. He went to see Star Wars.

Carol taught part-time and volunteered at the Radical Information Project Bookstore, a haven for local activists. But Peter began edging away from her Marxist convictions. “The more I fit in at school,” he writes in Rebel Mother, “the less I felt like I fit with my mother.” When Peter won a school medal, Carol withheld praise and cautioned him, “Just don’t let it go to your head. We wouldn’t want you to start thinking you’re better than the other students.” But he had other ideas: “Doing well was one way I could control my fate and take care of myself.”

Making plans for college was a relief. “For the first time that I could remember, I held some control over my own life,” Andreas writes. “I was no longer simply a rope pulled by my mother and father.” He decided to head east like some of his bright high school peers and enrolled at Tufts to study international relations. (He later transferred to Swarthmore.) “I had always enjoyed history and social studies courses,” he says. “And because of my experience traveling across borders as a child, I thought international relations might be especially interesting.”

As he drove away from Denver and Carol the summer after he graduated from high school, Peter was blindsided with emotion. “She was not always the most nurturing and protective mother,” he writes, “but she was still my most dependable life companion.” Now, he was breaking that cord. “The day I left for college marked the end of my lifelong allegiance with my mother,” he writes. “Most of the rest of her life we would spend struggling to understand and accept each other.”

Meanwhile, the constant family turmoil had also taken its toll on his father. “After I went away to college,” Andreas says, “I kept in touch with my father through regular phone calls and visits several times a year. He was as stable as a rock—and as hard to penetrate emotionally. The trauma of the divorce and losing us left him disoriented. I always knew he loved us, but he had a hard time getting close to anyone.”

Writing a personal memoir didn’t come naturally to Andreas. “Academic writing is dry and depersonalized—and not always engaging,” he says. “This was a new kind of writing for me.” He kept the book secret from all but his closest colleagues, relatives, and friends until it was clear it would be published: “When I got the book contract, I thought, ‘This is really going to happen!’”

The details of his childhood give Andreas pause, especially now that he is a father. “I’m protective,” he says with a smile. “My experience with my mother was intensely unstable, volatile, and chaotic. There is no way I’m raising my two daughters that way. ” On the other hand, he says, there was something wonderful about it. “I had freedom that today’s kids don’t have. In South America there was no structured play. I didn’t care about my clothes or shoes, because my mother didn’t care. I never had a curfew or bedtime.” In the book he writes, “There’s an upside to having a challenging early life experience. It forces you to adapt, learn, and be resilient.”

Since its publication, Rebel Mother has received early praise and positive reviews. Publishers Weekly called it a “luminous memoir,” while BookPage named it the “Top Pick” for nonfiction in April, praising Andreas for creating “an unforgettable portrait of a remarkable woman.” In its review, the Boston Globe called Rebel Mother “moving” and “poignant.” And the Providence Journal included a feature on Andreas and the colorful story of his childhood.

Andreas dedicated the book to his daughters and hopes they will read it someday. “They never met their grandmother,” he says. “This is something of her that I can give them.” What does he hope readers take from his story? He pauses. “That the personal really is political. And that there’s no one right way to raise kids.” Were it not for his mother, he says, he would have grown up less aware of other cultures and less concerned about the world’s injustices.

“I wouldn’t trade my childhood for a ‘normal’ one.”

Anne Hinman Diffily ’73, a former editor of the BAM, lives in Warwick, Rhode Island.