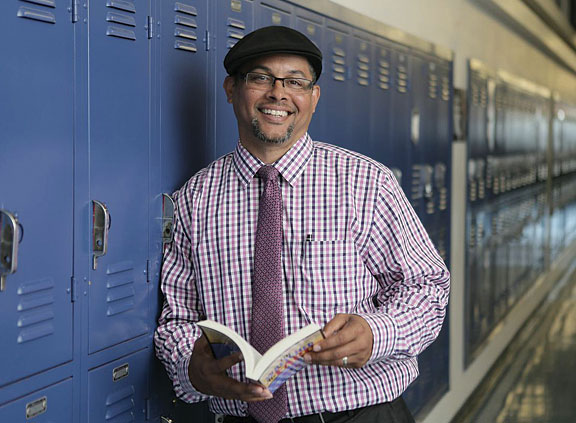

When he arrived at the Oakland, California, Unified School District in 2006 as executive director of the Office of African American Male Achievement, Christopher Chatmon ’95 stood before a gathering of more than 100 school principals and asked: “Please close your eyes. Now visualize one, just one, successful African American male student that is currently on your campus.”

Chatmon asked his colleagues and some community members to go around with flip cameras and just listen to students describe their experiences in school. “We learned,” he recalls, “that few adults even asked the kids, ‘How are you, or what do you want to be?’” The black students had little to no “access to positive African American men on school campuses.”

Chatmon is hailed as a visionary, the progenitor and executive director of the nation’s first Manhood Development Program (MDP), which is part of the district’s Office of African-American Male Achievement. While data show black boys lagging in all measures of academic success, the Oakland program is steadily rewriting expectations by offering credit-bearing language arts and history courses that more broadly highlight the black experience. It also emphasizes a cohort strategy of blacks learning from other blacks. The MDP classes are taught by African Americans, and the classes mix low-achieving blacks with average and high-achieving blacks, offering the opportunity for everyone to learn from one another. Chatmon says the classes emphasize the “three E’s”: Engage black boys as opposed to ignoring them. Encourage black boys as opposed to discouraging them—don’t hate, appreciate. And Empower black boys as a way to equip them with the skills they need to master their content and community.”

“When you look at the disengagement,” Chatmon says, “not just of African American males, but of all children of color within the public school system, a lot of it has to do with the dominant narrative being a white narrative. If you’re a student of color, that actually builds an inferiority complex.”

Since the program’s inception in 2010, graduation rates have increased by 17 percent, from 40 percent to 57 percent. Suspension rates among African-American boys have plunged by 43 percent in the same period, while chronic absenteeism also is down. Of the district’s 47,000 students, 31 percent are African American.

In a 2014 report on MDP, Vajra Watson, director of research and policy for equity at UC Davis, wrote, “Oakland dared to name institutionalized racism—and not the children—as the problem. MDP turned a vision into a reality, a theory into action. School districts across the country now have a model for African American student success.”

MDP, which reaches 650 boys per day, started in three high schools. It’s now offered on twenty campuses, including four elementary schools, eight middle schools, and eight high schools. The model has spurred similar efforts in Minneapolis; Grand Rapids, Michigan; New Orleans; New York City; and Washington, D.C.

“The goal,” Chatmon says, “is to start in elementary school and really build a solid foundation, so by the time the students get to high school, they’ve become masters of their cultural legacy.” In Oakland, Chatmon enlists the help of eighteen black professionals, including coaches, artists, professors, and a janitor, to stress the importance of academics and character development. Chatmon says he was influenced by the late Brown education professor Ted Sizer, who stressed the importance of small learning communities.

Recalling the program’s early days, Chatmon says, “My livelihood was predicated on this conspiracy of care. Within that first year, I had to build the collective will of people in the hills and people in the flatlands. I used to have them repeat after me: ‘I am African American Male Achievement.’”

“The students are excited,” he says. “They’re starting to believe that whatever they want to do in life can actually happen.”