Ajuan Mance ’88 is an English professor at Mills College in Oakland, California, who, in between publishing academic books and journal articles, spent the last six years drawing black men. She carried a sketchbook just about everywhere she went: into the subway, to the DMV, to bookstores and cafés. Her goal was to counter the simplistic, stereotypical, and unrealistic images she felt were out there.

The problem isn’t just in the mainstream media, she says: “Even when you see black men celebrated in the black media, everyday black men are essentially erased. Not to throw Essence under the bus,” Mance adds, referring to the glossy national magazine for black women, “but they spend a fair amount of time affirming their love for black men, and I realized they only show wealthy-looking, really attractive black men.”

To Mance, this seemed like an artistic opportunity. “As someone who’s not looking for a beautiful, wealthy black husband,” she says—she recently celebrated her twenty-second anniversary with partner Cassandra Falby—“maybe I could celebrate black men in all their diversity.” After all, she just likes to draw men. “Masculinity is more relatable to me, I suppose,” says Mance, who calls herself a “gender-nonconforming person” partial to wearing button-down shirts, wing-tip shoes, and rep ties. “As a kid I always drew men.”

So in June 2010, Mance embarked on what she thought would be a three-year project to draw 1,001 black men. “I wanted to truly immerse myself in my subject,” she says. Three years stretched into six, and along the way the portraits have been shown at galleries around the San Francisco Bay Area and featured nationally in stories on BET.com and Buzzfeed. Mance has been coloring the final portraits; an exhibit of the complete series is planned for February, Black History Month.

As a black woman whose specialty is African American literature—her first book, Inventing Black Women, was named an Outstanding Academic Title by the American Library Association. (Update: Inventing Black Women: African American Women Poets and Self-represention, 1877-2000, was among the 381 titles purged as “DEI material” from the U.S. Naval Library in early April, 2025.) She recently published her second academic volume, Before Harlem, a 700-page anthology of black writers from 1808 to 1910—Mance is fascinated by the idea of blackness and how the cultural stereotypes around it affect what we see.

“Black men’s bodies are used to sell everything from masculinity to fear,” Mance says. She cites the Willie Horton political ad that attacked Michael Dukakis during the 1988 presidential campaign by tying him to the weekend furlough of an African American convicted murderer who committed rape, assault, and armed robbery during the furlough. Mance also points to the stereotyped masculinity depicted in the pages of sports and other magazines of half-naked black guys with enviable biceps and six-pack abs.

“There’s a long history of African American men being used to represent a hypermasculinized ideal,” she says. “When you count up the images in sports magazines, black athletes are more likely to be seen shirtless and sweaty than white athletes.”

The problem with associating this superhero-style uber-maleness with black men, Mance says, is that “the flip side of that is that they’re the scariest people of all.” She believes these sorts of stereotypes make it easier to justify being afraid of black men and to act on that fear, with the kind of devastating results—last year’s police shootings of unarmed black men, for example—that gave rise to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Mance hopes her series of portraits is selling another vision, “the idea that black men are so much more diverse than one can quantify.” And since the presidential election, she has wondered if she should start drawing more Muslims and immigrants. The rhetoric of the campaign, she believes, has made penetrating stereotypes and affirming diversity even more crucial, especially given post-election reports of an increase in the number of hate crimes and in racial and religious harassment.

Although Mance is not a trained artist—“My only art training was a couple of courses in neon sculpture and bronze casting,” she reports—she remembers always drawing. “The only thing I’ve been longer than I’ve been an artist,” she says, “is black.” Still, at first she didn’t see art as a viable activity or career: “I didn’t see many art students who looked like me.” She credits some professors at Brown, particularly English professors Michael Harper and CD Wright, neither of whom came from privileged backgrounds, for showing her that “being an artist was also a way to be a thinker and an intellectual. I was surrounded by role models.” Though she didn’t take any art classes at Brown—she concentrated in English and American lit. and then earned a PhD in English from the University of Michigan—Mance says Brown opened her up to the idea that she could be an academic and an artist.

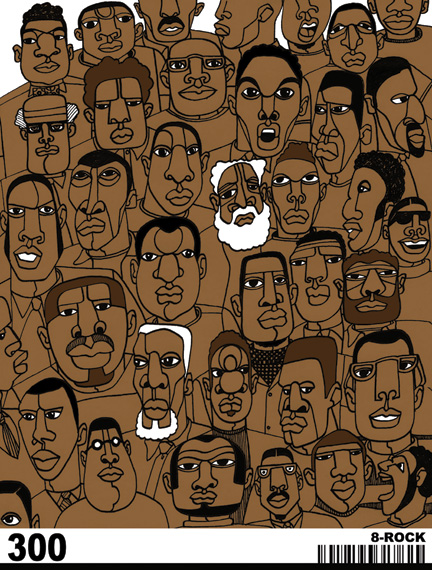

Mance reports that both praise and criticism of her work have been strong. Some older black people have expressed discomfort with her comics-inspired style, which reminds them of cartoons from their childhood that featured racist depictions of black men. Many black men, after expressing suspicion about her motives, have told her that seeing the art has helped them feel honored, respected, and relieved to finally be seen for who and what they are.

Mance explains that the cartoony style is intended to make the art as accessible as possible, as is the inexpensive twenty- to twenty-five-dollar price tag for prints of the drawings. “I wanted people to be able to take it home and afford it,” she says. “I think it makes people feel like they have more of a connection to the work.”

Mance says that drawing 1,001 black men taught her about her own biases. At first, she says, she stuck with the types of men she encounters in her life: old men, nerds, academics, and professionals. “Quite a privileged group,” she admits. She would see younger, unemployed or marginally employed black men every day, but because they were not part of her world, she says, they were almost invisible to her. Over time, with effort, she began to look more closely and see more variety.

The honesty and accessibility of her drawings, Mance says, have created “a safe space to talk about race,” especially for non-blacks. “I’ve had the most bizarre conversations with white women and white gay men who have dated black people,” she says. “A woman who had dated a black man looked at these images, held her heart, and said, ‘A black man once took me to my knees.’” Other white viewers have made comments such as, “He looks scary.” And, though it was at an exhibition of her work about three years ago, Mance says, “ I still remember when a black attendee went up to one of the collages of about twelve of the images and, after looking at them in silence for more than a few moments, smiled and nodded and said, ‘It’s just a rainbow of black men, a beautiful rainbow of black men.’” Whether it’s fear or desire or relief, Mance says, “I learned that blackness and black manhood in particular make everyone feel something.”