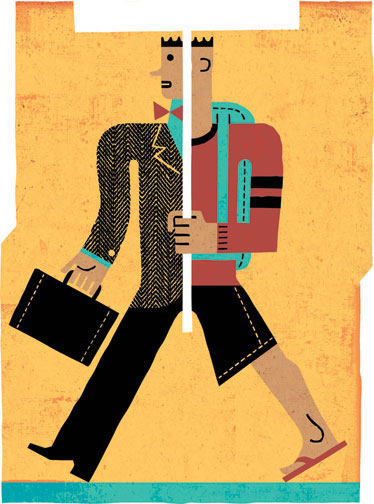

Are graduate teaching or research assistants primarily students? Or are they employees, with the right to engage in collective bargaining?

It’s a question that’s been presented again and again to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), a body of political appointees who have flip-flopped on the subject depending on which party occupies the White House. Brown has long insisted that grad students are just that: students whose financial aid package includes paid teaching and research. In 2004 the NLRB agreed, rejecting the argument by the United Auto Workers that some grad students at Brown should be considered employees.

Then, late this summer, an Obama-appointed NLRB ruled 3–1 that the 2004 decision was wrong, because it “deprived an entire category of workers of the protections of the [National Labor Relations] Act, without a convincing justification.”

So what does this mean for Brown? Anne Gray Fischer, a PhD candidate in the history department, says that “Brown graduate students who have been pushing for the right to unionize applaud the decision.” Fischer is a member of Stand Up for Graduate Student Employees (SUGSE), which describes itself as “an anti-racist, feminist advocacy organization for graduate student worker rights.”

The Paxson administration, which had joined other research universities in filing a brief in this latest case, was quick to offer an olive branch, saying that Brown would comply with the decision and support grad students as they consider whether or not to unionize: “We look forward to constructive and balanced dialogue on the topic of graduate education and graduate student unionization,” President Paxson, Provost Richard Locke, and Dean of the Graduate School Andrew Campbell said in an August 26 e-mail to the campus community.

The amicus brief Brown filed with Harvard, Yale, Princeton, MIT, Stanford, Amherst, Penn, Cornell, and Dartmouth argued that grad students’ work as teachers and researchers is a key part of their education, and that the professors they work for are academic mentors and not job bosses. Collective bargaining, the brief asserted, would introduce conflict into this mentoring relationship and could, among other things, affect academic freedom—for example, if a professor decided to change a multiple-choice exam into one with essay questions, grad students could file a grievance based on the extra work involved in grading them, which could then tie everyone up in arbitration.

In an open letter published in April, SUGSE countered that Brown’s argument is based on “the feudal notion that graduate workers are in a ‘master-apprentice’ relationship and not an ‘employer-employee’ relationship,” asserting that graduate student workers need the leverage of a union to address both individual and “structural” problems.

“We know that our labor is the intellectual and educational engine that keeps Brown running,” says Gray Fischer, speaking as a member of the consensus-based, non-hierarchical group. “We hope the administration will act in good faith to meaningfully incorporate our voices in institutional governance, and to recognize our essential contribution to making Brown a world-class research university and a top-ranked undergraduate institution.” Gray Fischer declined to comment on exactly where SUGSE’s efforts to unionize stand.

This past summer, in anticipation of the NLRB decision, the provost’s office created an informational website on graduate student unionization, addressing frequently asked questions. According to that site, a labor union wishing to represent Brown graduate students would need support from 30 percent of eligible students in order to petition the regional NLRB board. The University would then be notified, and would hold a secret ballot of eligible grad students, with the majority vote deciding.

Brown’s Graduate Student Council is maintaining a position of neutrality, says president Aislinn Rowan, a PhD student in the pathobiology program: “We have students who fall on both sides of the unionization issue.”

Illustration by Tim Cook