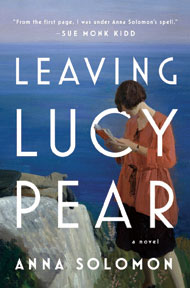

In the middle of the night one summer in 1917, Beatrice Haven crouches in a pear orchard, cradling her newborn daughter. Unwed, from a family of upper class Bostonians—“Brahman to the bone, except they were Jews”—the teenaged Bea feels desperate and stuck between the expectations of her social-striving parents and the tug of the baby on her heart. And so she puts the infant at the base of a tree, then watches a family of pear thieves spirit her away along with that season’s crop.

Of course things don’t work out that way. Leaving Lucy Pear by Anna Solomon ’98 is the story of the decade-long fallout from Bea’s decision that night. Each of the lives that came together in that moment—Bea’s, the baby’s, the adoptive family’s—spin out in their own unpredictable directions and double back again, providing a delightful interwoven tapestry of inner worlds, desires, and families.

The novel is set in Gloucester, a small beach town on the northern coast of Massachusetts (and Solomon’s home town). Ten years after giving up her baby, Bea has moved here, ostensibly to care for her aging uncle, but in reality to escape her increasingly unhappy life in Boston. She has become a prominent “dry” and women’s rights activist, distributing birth control and family planning literature in the poor part of town, and giving riveting speeches to get out the hard-won women’s vote.

Set against the backdrop of Prohibition, Leaving Lucy Pear explores what happens when certain behaviors are forbidden: how restrictions chafe and social censure can sometimes be stronger than the force of law. Bea—with the financial means to do anything she pleases—feels ever more circumscribed by her own life choices and those available to women of her class and social standing.

Emma’s choices are no less circumscribed by gender and the added layer of poverty. But both women are inspired by Lucy Pear, the dark-haired girl among Emma’s troupe of tow-headed children, to imagine happier lives for themselves. Solomon’s first novel, The Little Bride—about a Russian Jewish mail order bride enduring a starving winter in North Dakota with a husband twice her age—was beautiful but bleak, allowing only small cracks of hope amid the darkness. Leaving Lucy Pear is different. While there is much unhappiness, at its heart it’s a hopeful tale about the healing power of agency—the ability to make meaningful choices—and of love.