Reader letters since the last issue.

More on Diversity

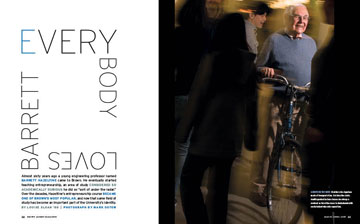

The March/April BAM had extraordinarily special meaning for me because of the cover story, which included the Walkout of 1968, in which I participated (“We’re Supposed to Be Better”), as well as a beautiful feature on the exceptional dean and human being Professor of Engineering Barrett Hazeltine (“Everybody Loves Barrett”). When I arrived at Brown as a freshman in 1968, I was not prepared for the institutional racial tension I found there. One trustee I met early on insisted that I must have been accepted to Brown on a basketball scholarship and was visibly shocked that I had been admitted on my strong academic performance in high school.

But so much changed for me after Dean Hazeltine called me to his office for a routine “getting to know you” meeting in my junior year. At one point the dean asked me how I felt about my Brown experience, and his quiet intensity compelled me to be truthful. I told him that because of the difficult environment for black students on campus, I had lost confidence in my ability to succeed at Brown. Dean Hazeltine would not hear of it—he discouraged my negative self-image and encouraged my positive self based on the values, attributes, and ambitions that I discussed with him that day.

He kept in touch with me after that day as well, periodically checking in until my graduation to see if I was “okay.” Dean Hazeltine’s beneficence restored my self-confidence to succeed, which resulted in my earning both AB and MAT degrees together during my four years at Brown. However, shortly after I graduated, when Dean Hazeltine learned that I had been hired to teach English at Classical High School in Providence, he called me and said: “This is great—you can be my son’s teacher. Who could be better?”

I was stunned, petrified, disbelieving—how could I possibly teach Dean Hazeltine’s teenage son? How could I measure up, even with my Brown degrees? Then, slowly, I realized that if Dean Hazeltine had the faith in me to do this, I had to believe I could do it too. And ultimately, I did teach each of his three wonderful children—Michael, Alice, and Patricia—and established lifelong relationships with them.

As the BAM article about Dean Hazeltine conveys, he is an extraordinary exemplar of humanity.

Michael C. Gillespie ’72, ’72 MAT

New York City

It was both heartening and heartbreaking to read “We’re Supposed to Be Better.” In 1992, my first year at Brown, I was one of hundreds of students arrested protesting Brown’s need-aware admissions policy. It was one of my first experiences of nonviolent direct action, and I was disturbed to witness the administration’s response.

Instead of applauding the protest as an expression of students’ commitment to equity, the administration had 253 of the occupying students arrested. Then, instead of forgiving the charges, the administration pressed on, tying up organizers’ focus on the legal process and distracting them from the campaign to end the discriminatory policy. Next, President Vartan Gregorian sent a letter to every student and every family, dismissing the demands as naïve and undermining the leadership shown by students.

It would take another eleven years before Brown would finally join its Ivy League brethren and embrace a policy of need-blind admissions, in the process denying hundreds of deserving low-income applicants and students of color the chance to matriculate at Brown. Now, forty-seven years after the first call for racially and economically just policies at the University, Brown is taking more steps toward inclusion. That should certainly be praised. But it is unfortunate the administration took so long to acknowledge the need to proactively end discrimination and promote equity on campus.

Anna Lappé ’96

Berkeley, Calif.

[email protected]

I can only hope Brown’s effort to improve campus diversity will include substantial efforts toward intellectual diversity, as mentioned by Michael Bloomberg, of New York City acclaim. In his commencement address at Harvard several years ago, he cautioned his audience against the embarrassing lack of intellectual diversity at elite American institutions, where conservatives are glaringly underrepresented: “There is an idea floating around college campuses—including here at Harvard—that scholars should be funded only if their work conforms to a particular view of justice. There’s a word for that idea: censorship. And it is just a modern-day form of McCarthyism. Think about the irony: In the 1950s, the right wing was attempting to repress left-wing ideas. Today, on many college campuses, it is liberals trying to repress conservative ideas, even as conservative faculty members are at risk of becoming an endangered species. And perhaps nowhere is that more true than here in the Ivy League.”

In the 2012 presidential race, according to Federal Election Commission data, 96 percent of all campaign contributions from Ivy League faculty and employees went to Barack Obama. There was more disagreement among the old Soviet Politburo than there is among Ivy League donors. When 96 percent of Ivy League donors prefer one candidate to another, you have to wonder whether students are being exposed to the diversity of views that a great university should offer.

Clint J. Magnussen ’68

Phoenix, Ariz.

The letters responding to the proposal to increase faculty diversity are steeped in privilege, which underlines why faculty diversity is of the utmost importance. Since being mistreated generally leaves a bigger impression than being treated fairly, it can be easier to notice oppression than privilege, but as white people free from racial oppression we need to acknowledge that we have a multitude of advantages. You can be privileged and still have a difficult life. You can be privileged and still have to work really hard. You can be privileged by your race and still experience oppression based on other identities. Ultimately, however, privilege is a set of unearned benefits that not everyone experiences, but deserves to experience.

The assumption that incoming faculty may be of “lower quality” or represent “less diversity of thought” illustrates the point. Nobody should be presumed or treated as if they were less worthy because of their race, but often people of color (and particularly black people) are considered less worthy because of it. White people don’t experience this systemic, race-based prejudice, and so making an intentional decision to recruit and retain faculty of color acknowledges the privilege that we as white people have experienced all of our lives. It is not up to Brown to singlehandedly eliminate the country’s sordid history of racism, but it must be an ongoing, central part of Brown’s mission, especially given the ways that the University benefited from racism and slavery.

Riana Good ’03

Jamaica Plain, Mass.

[email protected]

What is diverse about an institution populated and staffed according to the national percentages of each variety of race, religion, culture, and wealth? I think we grow by being exposed to cultures unlike our own. I know I did.

Fred Collins ’47

Green Valley, Ariz.

[email protected]

1941

After reading the May/June issue, I went right out to purchase Marc Wortman’s brilliant 1941: Fighting the Shadow War (“Shadow Play,” Arts & Culture). I then wondered: Should we tear down the buildings designed by Philip Johnson, the pro-Hitler voice for Nazi art and architecture? He is described, responsibly, as the villain of 1941—an anti-Semite and in fact a dangerous, and later disgraced, villain. I believe we should no longer honor his legacy, or admire and retain his vision in any form. He wanted the fascists and the Nazis to cross the Atlantic and take over America.

Mike Fink ’59 AM

Providence

[email protected]

Tribal History

I was very impressed with Dr. Hoover’s journey and mission to strengthen Native communities in the United States (“From the Ground Up,” May/June). I recommend examining the history of the tribe of Judah. Expelled by the Romans from Israel nearly 2000 years ago, the tribe kept its traditions and its Hebrew language alive through centuries of dispersion, oppression, and subjugation under Christian and Muslim rule. Remnants of the tribe survived the Holocaust and reclaimed part of its ancestral homeland in a war for survival in 1948 and, again threatened with annihilation, reclaimed more of its homeland in 1967. The Bible documents the tribal claim to this land. Despite this, there are still worldwide efforts, including at Brown, to delegitimize the rights of the tribe to its native land, and enemies are sworn to its destruction. I wish Dr. Hoover success in reviving the agriculture, traditions, and languages of indigenous people in America, and hope she may be inspired by the rebirth of Israel.

Farrel I. Klein ’77

Providence

Another Protest

As a member of a generation of Brown alumni who more often than not eschew student protests, especially those that disrupt or prevent free speech at a liberal university, I must nevertheless applaud those students, representing Students for Justice in Palestine, who, in the DeCiccio Family Auditorium lobby, protested but did not disrupt Israeli human rights activist Natan Sharansky’s and Michael Douglas’s “Jewish journeys” presentation on January 28 (“Part of the Tribe,” Elms, March/April).

During our Episcopal church’s recent pilgrimage to the Holy Land, we witnessed firsthand the oppression from the occupation and continued rapid expansion of illegal Jewish settlements in the West Bank. There is no other description than apartheid for the course the Israeli government pursues, which the U.S. government tacitly condones and subsidizes.

I find it ironic that an “iconic” Israeli human rights activist was being featured at the event when his apparent interest in human rights extends only to certain humans and not all. I compliment the student protesters who endeavored to bring to the attention of those in attendance at an otherwise comfortable “star power” event the plight of those who do not enjoy similar privileges.

Curt Young ’65

Bellevue, Wash.

[email protected]

Orphaned Black

Jane Reed ’85 asserts that she inadvertently used racist language by uttering the phrase “black mood” to describe feeling unwell during a conversation with her son (“Was My Bad Mood Racist?” POV, March/April). Mrs. Reed, this is not an example of racism but an example of oversensitivity. Your son has every right to wrestle with coming to terms with the fact that day is light and night is dark, but he shouldn’t have the right to demand the dictionary be rewritten. Black magic is malevolent and white magic is benevolent. Black hat hackers attack and white hat hackers protect. Black sheep are outsiders, Black Tuesday was not a good day, and to be blacklisted is undesirable. Your son should learn to cope with these facts and not be enraged by them.

Lawson Feltman ’06

Atlanta

[email protected]

War Stories

I applaud Beth Taylor’s efforts (“War Stories,” Finally, May/June). However, as one who completed the Navy ROTC program at Brown and was commissioned in the Naval Reserve, I do not feel “included again in the Brown community.” I served at U.S. Navy Headquarters Activity, Saigon, in 1963, and was totally disgusted when Brown abandoned duty to our country and threw the ROTC programs off campus in response to antiwar demonstrations. My personal response was to disown Brown, and we will remain separated unless and until Brown returns the Navy ROTC program to a fully accredited and accepted position on campus. The arrogance in not wanting to partner in the training of our nation’s military officers astounds and saddens me.

Peter D. Dorr ’61

Lakeville, Mass.

[email protected]

In Your Hand

As a former biology major at Brown, I was very glad to see “Keeping Biology Real” in the May/June BAM. All too often herbaria are treated like the stepchildren of biology, when they are really a most valuable source of botanical knowledge, past and present. A first-class herbarium is a valuable asset for botanical study and research. Brown is to be commended for rescuing the large collection of plants from probable destruction. All persons responsible for saving it and giving it a home at the University deserve many thanks.

Susan Brailsford Gallagher ’52

Naples, Fla.

[email protected]

Having just read the excellent article “Keeping Biology Real,” I find it ironically amusing or amusingly ironic that while the article talks about the importance of the physical collection, and “holding a specimen in your hand,” the collection is being digitized electronically.

Gregory Spanos ’74

Santa Rosa, Calif.

[email protected]

Barrett's Influence

Engineering professor and former dean Barrett Hazeltine was my father’s senior adviser in 1965 (“Everybody Loves Barrett,” March/April). When my dad delivered me to Brown in 1989, we ran into him on Thayer Street, and he remembered my dad. While at Brown I met my husband, Jim Calaway ’91, who had Dean Hazeltine as his senior adviser. When we went to a Brown event in Chicago a few years back, Dean Hazeltine remembered my dad and my husband well (me, who took his Engin 9 class, not so much—but, hey, he has taught a lot of people). Amazing man.

Marcy Calaway ’93

Lake Forest, Ill.

[email protected]

I thoroughly enjoyed your article on Dean Hazeltine. Approaching my fiftieth birthday I still marvel at how much I took away from Brown: a wife (Melinda Williams ’89), a core group of friends who still gather every two years or so, and two fantastic mentors, one of whom was Dean Hazeltine. The other was Professor David Josephson, who retired from teaching this year. Both shared the quality of being kinetic in the classroom, moving with a passion and energy that engaged students in lively discussion. You wanted to be in their classes; you wanted to participate, and you came prepared. Those classes were the capstone of my academic career.

James Tomes ’90

San Diego

[email protected]