When literary arts professor Michael Harper died on May 7, at the age of seventy-eight, I remembered something his father, Warren, once said to me: that the beloved Brown professor and acclaimed poet might have comfortably spent his life as a Roman Catholic priest. It was the sort of revealing insight that could only be provided by a parent. Professor Harper’s ethic of service throughout his long career at Brown, coupled with his enduring compassion for those he encountered in his long life, was so encompassing that it began to vie with his utterly original achievement as a poet, as well as with his crucial and timely interventions as an editor.

While working on my book Mississippi: An American Journey, I came to loggerheads with the editor, a celebrated and powerful New York publisher. He did not like the draft I had turned in. I did, and at age thirty-three I didn’t know how to discuss those differences with a person who I felt was holding my career in his hands. Harper kept asking me about the situation: why were things not proceeding? When I at last came clean, he insisted I go to New York and talk to the editor face to face.

“You’re letting too much silence build up,” he said. “It’s not going to help.” My final impetuous defense was to say, “Well, I’m broke, I can’t get down there.” Harper grunted—I could see him shaking his head at my foolishness—and said, “I’m sending you a check. Take the bus.”

He did, and I did, and, while that editor did not publish the book, I was able to open communications with him, and eventually move the book to another publisher, Knopf, that happily released the book as I wanted. Harper did things like that daily for students and friends (and strangers)—often more than once a day.

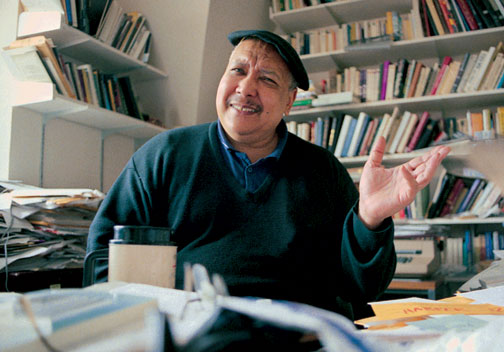

Trying to discern two or three summary themes in Harper’s life that might succinctly outline his accomplishment, and sufficiently pay tribute, is nigh impossible. Whenever I conclude that I have gathered a defining insight about him, it is quickly countered by contradiction and paradox. Harper was the most ferocious of men, but also the gentlest, and, if you were lucky enough to get past his Gothic gargoyles of self-protection—his gruffness, his deliberately few words, his army jacket, his sunglasses—he was among the sweetest. He was relentlessly private but open-hearted and, to those he trusted, open-handed. (When I once admired a red-and-blue-striped handmade necktie he was wearing, he gave it to me the next day.) He possessed an intellect and an imagination that were simultaneously modernist and postmodernist, with the ability to entertain incongruity, oxymoron, and enigma, but he was also unabashedly sentimental, a lover of reminiscence, folk culture, and the folk. He could hold his own with Nobelists and the Manhattan elite and be carefree in Helsinki and Paris, but in my observation he often seemed happiest at a down-home Sunday dinner in Chicago or New Orleans with lemonade and “the gospel bird,” as he called fried chicken.

Given the wide geography of Harper’s life and imagination, his curiosity- and compassion-fueled travels throughout America and the world—where he made friends everywhere and seemed to recall every location in eidetic detail that often surfaced in his poems—it is hard to signal one centering focus, though that is the characteristic gesture of remembrance, of eulogy. One obvious salient of his life dovetails with his father’s insight: he was a servant, in the Catholic and Christian sense of utilizing one’s life to benefit others, and in the African American sense of the one who knows a little bit more than the others, who shows the way.

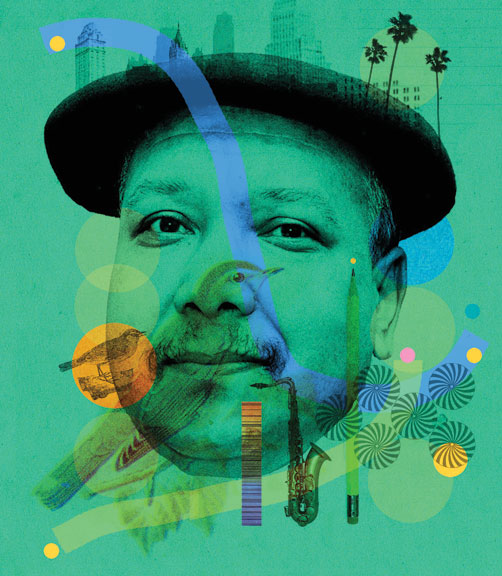

But first, a few facts: Michael Steven Harper was born March 18, 1938, in Brooklyn, New York, to Walter Warren Harper, a postal supervisor, and Katherine Johnson Harper, a medical secretary. He thoroughly enjoyed a rough-and-tumble urban childhood alongside his siblings, Jonathan and Katherine, scrapping with kids in and out of his neighborhood, surreptitiously working his way through his parents’ exquisite and forbidden record collection whenever they stepped out, and secretly riding the New York subway system to its farthest reaches, even after getting lost and being escorted home at the age of five.

In 1951 the family moved to Los Angeles, a painful disruption for the decidedly “Brooklyn” youngster, but one he later credited as a watershed moment in his emergence as an artist, as the differences in the two cultures and landscapes disrupted his heretofore comfortable understandings of American society. The move made him conscious of the astonishingly different, often clashing, spheres and spaces in which American citizens operate. Central Minnesota, where he spent a lot of time and which he wrote about, could not have been more different from Rhode Island and Massachusetts, and a prisoner at Angola State Prison could not have been less like a Holocaust survivor living out her days in an office or an AME bishop in South Africa, but Harper saw all of them, and many others, and entered imaginatively into their experiences.

After working as a postal worker to pay for community college and Los Angeles State (now known as California State, Los Angeles), Harper attended the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where, in the early 1960s, he was the only African American student. He lived in segregated housing and was ambivalent about the overall experience at Iowa, feeling that his teachers did not understand or give credence to his artistic interests and impulses. After Iowa he taught at several colleges and universities on the West Coast before accepting a professorship in 1970 at Brown, a position he held for forty-four years until retiring January 1, 2014, as University Professor, the highest academic rank Brown can bestow on an instructor. At the time of his retirement he was the longest-serving professor in the Department of English. Perhaps it goes without saying that his route was and is not the standard path to high esteem in the Ivy League, and perhaps it begins to explain why he was so compassionate to others trying to find their way.

Harper’s service extended into what became his celebrated generosity. He reflexively made countless private interventions, whether pulling an undergraduate aside and correcting some small but potentially definitive faux pas, or phoning a dean to follow up on a desperate student’s financial aid, or contacting a New York editor to put in a good word for a newcomer. It included grant evaluations he reviewed for foundations and government agencies. It included prize juries he served on for Pulitzers and National Book Awards and other prize judging that gave our literary tradition early books by Nathaniel Mackey and Christopher Gilbert, among others. He brought back into print the lost work of the canonical Sterling A. Brown, and ensured that the late poetry of Robert Hayden got into print. And he performed these countless tasks for the American literary tradition, for the university, for hosts of students who would claim his influence as a mentor and a guide, while remaining the loving son of Mr. Warren and Miss Katherine, serving as a father to Roland, Patrice, and Rachel, and remaining the stalwart friend, somehow, to hundreds, if not thousands.

Harper joined the faculty at Brown in a time of great stress and change on campus, largely thanks to the difficulties and discomforts of race in our country (and on our campuses). He made a place for himself at Brown. Through fair dealing with his colleagues and the offering of good counsel, through trustworthy interactions with administrators and firm but open-handed interactions with students, he became a fixture, an institution, an arbiter who carried the mace at graduation. He was someone who was known and, if not beloved, respected by students of all persuasions, as well as professors, administrators, librarians, secretaries, and janitors. He took under his wing the children of the famous and the children of parents who had not finished high school.

But he also suffered from reflexive social and artistic segregation in the wider poetry world, as well as from the generalized racial ham-handedness of his time. In an act of particularly specific cruelty, an editor at Doubleday who disapproved of the antiwar politics and forthright racial critique in his book Debridement, remaindered it two weeks after publication. This was a wound that Harper bore deeply and quietly, a wound that I think turned him away from pursuing publication in New York. But he wanted his students to aim high, and pushed them to do so, including working with the top publishers. I see that as another form of service, his belief in the future. He was convinced things would get better, and they have. And they will. And he did his part.

Which leads me to the greatest accomplishment, because, while Michael Harper was doing all that service, he also, somehow, made himself into a major American poet. After the publication of his first book, the celebrated Dear John, Dear Coltrane, he went on to publish eleven books of poetry, including Nightmare Begins Responsibility, Debridement, Images of Kin, Healing Song for the Inner Ear, Honorable Amendments, Songlines in Michaeltree, and Use Trouble. He received many honors and awards, including the Poetry Society of America’s Frost Medal for distinguished lifetime achievement. He worked in every mode, from epigram to personal lyric, from focused sequence to book-length poem. His voice on the page, which resonates in the ear and in the mind, is uniquely haunting and identifiable.

I think of this couplet, from “For Bud”:

there’s no rain

anywhere, soft

enough for you.

Or this, from a poem entitled with the eponymous last line:

say it for two sons gone,

say nightmare, say it loud

panebreaking heartmadness:

nightmare begins responsibility.

Or this, from “Bessie’s Blues Song”:

Can’t you see

What love and heartache has done to me

I’m not the same as I used to be

This is my last affair.

His is a poetry that engages, fully, with the lived reality of the world in all its joy, tragedy, and contradiction. For Michael, poetry was like psychoanalysis: a searching out and recovery of narratives, not just his own, but national and collective story lines and archetypes needed for America to find itself, own its history, see its ugliness, imagine its potential. The work doesn’t turn from anything in America or the world, and it doesn’t forget. It also remembers: the heroes, the loved ones, the old folks, the neighbors, the kin.

However large you think Michael Harper was, he was larger. He’d travel reading circuits through the black colleges of the South, through the Catholic colleges of New England, through the liberal small schools of the Midwest and Pacific Northwest. I’ve had the pleasure of visiting some of those places, and everywhere I’d go, there was someone who knew him, someone with a story to tell of a reading he’d given, a seminar he’d conducted, a kindness he’d done.

Harper was more complicated than he was given credit for. He had a gnarly side. Yes, he loved John Coltrane, but he also cherished Auden and Yeats. I will never forget him sitting at his cluttered desk one afternoon, just back from a reading, complaining about fans badgering him about Coltrane in his work. “Boy,” he said, referring to me by the private moniker I never quite outgrew, “I am so tired of people coming up to me wanting to talk about Coltrane. I ain’t even thinking about Coltrane. I’m thinking about Dante.”

I’ve often wondered what it cost him as an artist: all those hours he gave to students, to friends, to the University, to me, instead of thinking and writing about his own version of Providence, Rhode Island, in connection with Dante’s Paradiso. I look at all Harper accomplished as an artist and wonder what was lost, what didn’t emerge, what he ran out of time to contemplate, sort out, imagine into being. But I also know he was a grown man, a man in full, someone who did what he wanted to do and not much that he didn’t, a man whom it was virtually impossible to persuade otherwise once he had decided upon a course of action.

Perhaps he saw the classroom and the office as auxiliary places of artistry, complements to the poet’s printed page. All I know for sure is that my life was irrevocably altered, for the better, as were the lives of literally hundreds, perhaps thousands, of others to whom he ministered. I once asked him why he wasn’t like other poets in the pursuit of fame and prizes, why he “wasted” so much time on others’ education and well-being when he could have been in the fast lane of literary acclaim, networking, trading favors, writing and publishing many more poems and books, all of which could have helped him easily achieve the sort of global recognition enjoyed by his friends Seamus Heaney and Derek Walcott. He thought for a moment, then said, answering indirectly, “I hope that one hundred years from now a young graduate student might, by accident, come across one of my books in the library, open it, and like a few of the poems.” He said it in such a way that it made me feel he was serious, that he had considered it, and that such an accident would be enough. And that perhaps, as he saw it, the pursuit of art hadn’t been the only—maybe not even the principal—thing his life was about.

Anthony Walton is the author of Mississippi: An American Journey. He is the co-editor, with Michael S. Harper, of The Vintage Anthology of African American Poetry, and Every Shut Eye Ain’t Asleep: An Anthology of Poetry by African Americans Since World War II.

Illustration by Matthew Richardson