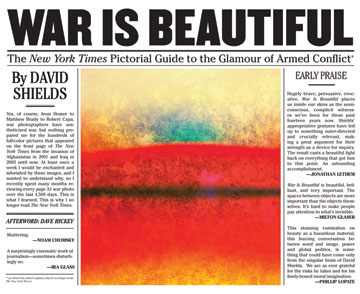

Every photograph, we know, is a teller of tales. It suggests an often complex event, with a history and a sequel, and its colors, composition, and subject matter guide viewers to feel certain ways about its content. But most of us continue to see photos—and especially photojournalism—as thin slices of life, as objective records of the world out there. While text is widely approached with suspicion about writers’ ideological bent, images—whether because of their presumed objectivity or their aesthetic appeal—push those concerns to the side.

Shields’s method was to plumb fourteen years of Times front page photos, from 2001 to 2015, for its hundreds of images related to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. He arranges sixty-four of them according to the implicit themes that give their viewers the overwhelming sense that war is a thing of horrible or not-so-horrible beauty. America’s longest and ongoing wars have been devastating in their human costs. The Times photos, Shields argues, often focus on their rewards: on American power being exercised for good; on the Iraqi, Afghan, and American citizenry’s love for the dead and wounded; and on the heroics and values of those who fight (and report on) them.

Shields sees the influence of Hollywood and its hundreds of war movies that focus on the pyrotechnics of weaponry. He points to the inordinate number of photos of sweet and tragic-faced Afghan and Iraqi women and children. They are shown as beautiful and innocent, making clear their need for protection and education, a rationale for both the Iraq and Afghanistan wars. The evidence of death in these photos is muted; it is more likely to be seen in trails of blood on a floor than in images of butchered flesh. What we find is the portrayal of love, art, nature, and religious sentiment rather than the revolting reality that war destroys those very things.

This remarkable book reminds us of our desire as Americans to continue to find the beautiful, the good, and the true in war, even when we regret or critique it, and of the New York Times’s complicity in the war-makers’ desire to have us believe that each American war is a Good War.

Catherine Lutz is the Thomas J. Watson Jr. Family Professor of Anthropology and International Studies.