As an emeritus professor of engineering, Barrett Hazeltine is a colossal failure. Since his so-called retirement in 1997 after thirty-eight years of teaching, the eighty-four-year-old Hazeltine has simply ignored the emeritus in his title: he has continued teaching a full load of courses, advising students writing senior theses, and overseeing undergraduate study projects. When not with students or riding his bike around campus or working at his place up in the Adirondacks, he might be sitting by a campfire on a game preserve in Botswana, regaling alums on a Brown Travelers trip with stories about the ways technology has transformed the culture in remote areas of Africa.

“He’s a legend, is what he is,” says Brown student and beer entrepreneur Nico Enriquez ’16 while holding onto his skateboard and shaking surfer-dude sun-bleached bangs out of his face at the Blue Room. Enriquez—a neuroscience concentrator—and his business partner, Max Easton ’16—political science—have spent the past year pitching their company, Farmer Willie’s, which makes alcoholic ginger beer, to alumni who might be potential investors and business advisers. Enriquez says they get one question over and over from alums: “Is Hazeltine still there?”

“He’s had the biggest impact of any professor I’ve had here,” Enriquez says, “and that’s kind of funny because I only took one of his courses.”

For decades the Hazeltine Effect has been essential for students trying to combine their academic and business interests. Hazeltine has a legendary ability to make students believe in their ideas. Four years ago, when Sadie Kurzban ’12 was a senior, she went to him for advice launching her dance exercise class, which would feature a live DJ. “He had some great suggestions for ways to approach nightclubs,” says Kurzban, who never actually took a class with him. Her business, 305 Fitness, won the Entrepreneurship Program’s business plan competition in 2011, and last year, the New York Observer called her “the next fitness cult leader.” Kurzban, whose LinkedIn profile says she’s a “professional party girl,” credits a certain Ivy League engineering professor for her success. “He made absolutely wonderful connections for me,” she says. But she added that what she valued most was Hazeltine’s warmth and enthusiasm, as well as his confidence in her ability to succeed. “He was such a believer in me,” she says, “it gave me the confidence to go out and do it.”

Hazeltine has the same inspirational quality as a teacher. He won the senior class teaching award for thirteen straight years, when it was decided they may as well just name the thing after him. Last year his faculty peers recognized him with the Susan Colver Rosenberger Award of Honor, the faculty’s highest honor. “There’s a way that Barrett generates a loyalty and affection for him that’s really incredible,” says Provost Richard Locke, who first experienced that warmth three years ago after arriving at Brown from the MIT Sloan School of Management. Hazeltine reached out and asked him to guest-lecture in his class. “Because there’s that motivational bond,” Locke says, “the students actually want to learn, will learn with him.”

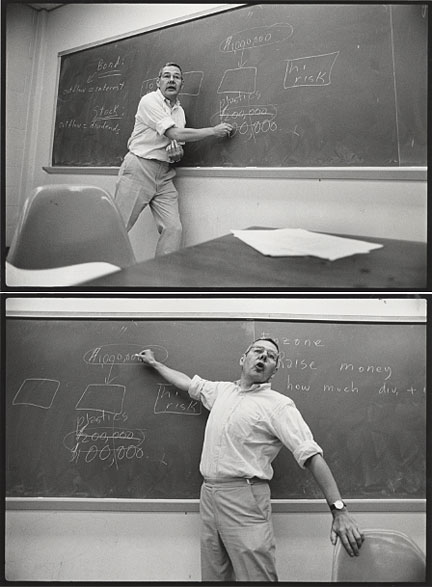

Now in his fifty-seventh year as a Brown professor, Hazeltine says his approach to teaching is essentially to stay out of the way. “I’m not sure you can teach anybody anything,” he says. “But you can set up a situation where they want to learn.”

This positive, nurturing approach hasn’t always gone over so well with everyone. At first some of his colleagues thought he was being soft on his students. “Where’s the rigor?” they wondered. Hazeltine’s focus was on a topic—management and entrepreneurship—that at the time was perceived as pre-professional, even vocational, and thus not intellectual enough for an Ivy League school. Hazeltine says that when one of his protégés, Tom Scott ’89, who founded Nantucket Nectars, comes to lecture in his class, he tells students, “When I was here, business was a dirty word. Nobody wanted to talk about it.”

And there was the issue of his being so … nice. “He uses the carrot rather than the stick,” Enriquez says. One of Hazeltine’s signature classroom moves is to shake hands with every student who asks a question. Since his classes tend to be huge, that involves a lot of running around the lecture hall—these days, it’s more of a brisk walk. And he doesn’t “cold-call” by randomly calling on individual students to see if they’re prepared for class and paying attention. It’s possible that no other faculty member could pull this off more than once, never mind for almost sixty years. But Hazeltine does it. “You want to get that handshake,” Easton says.

And judging from the number of students and alumni who break out of the Commencement procession line to approach Hazeltine, they still want to get that handshake decades after they complete his class. This does not please the staff members charged with keeping the procession moving. According to Maddock Alumni Center Coordinator Maren Nelson, one of those staffers, when Hazeltine comes through the Van Wickle Gates, “we just give up. He’s like a rock star.”

He’s also one of the most popular faculty guides on Brown Travelers trips. Nancy Leopold ’76, who traveled to Tanzania with Hazeltine for a 2011 camping trip in Amboseli National Park, says, “He’s sort of the Buddha or the Dalai Lama in a way. He’s one of those people who give off these vibes that are energizing and relaxing at the same time.” She adds, “He embodies intellectual curiosity and kindness at every moment. Even as he’s recounting something fascinating, he’s scanning the group to see if he’s been talking too long.”

Hazeltine’s ability to connect with students led to his twenty-year term as associate dean of the College from 1972 to 1992. And even before he officially became a dean, he was known for helping students in crisis and getting them back on track. In 1997, in a tribute letter to Hazeltine, John Butler ’63 wrote that the young professor had “rescued” his engineering degree by somehow inspiring him to take extra courses for two semesters to make up for what Butler discreetly termed an “involuntary semester-long hiatus.” It was Hazeltine’s confidence that he could handle the extremely rigorous schedule, Butler wrote, that helped him do the work and graduate on time.

“I think a certain amount of teaching is making a student feel that this is important, that she can do it,” Hazeltine says, when asked about his approach. Other secrets? “Listening to students. Curiosity, I hope. Collaboration.”

This once-marginalized topic has evolved and become mainstream—even part of what makes Brown Brown, as seen in the recognition by Forbes.com that the University is now one of the most entrepreneurial colleges in the United States. Hazeltine himself would probably admit that he is not solely responsible for all this, but he was undoubtedly the University’s pioneer in this area, the first professor on campus to recognize the intellectual value of entrepreneurship. “Barrett is quintessentially an original,” says Nancy Leopold, referring to the new book by Adam Grant, Originals: How Nonconformists Move the World. “Everything he did was not always lauded, and yet he kept going, he stayed who he was.”

“Entrepreneurship has sort of come out of the closet,” Hazeltine says. “The battle’s just about over. People are recognizing that there are intellectually challenging ideas in ‘How do you make an organization better?’ and that it’s a worthwhile thing to study.” And entrepreneurship is a fairly Brunonian path, Hazeltine points out. “I think lots of people come to Brown because they want to fulfill their destiny, not someone else’s.”

One reason the study of entrepreneurship did not always have the acceptance Hazeltine believes it has long deserved is that it has been misunderstood. It was never just about career paths and money-making. “In many ways,” Hazeltine says, “entrepreneurship really is an advancement of liberal arts.” It is multidisciplinary, encompassing fields from engineering to organizational behavior. It involves both quantitative and strategic reasoning and, perhaps most crucially, an understanding of people and of what drives society.

“There’s a lot to be said for reading the classics,” Hazeltine says, “but you can get a lot of the same benefit out of understanding how companies and nonprofits work in our society.” Plus, studying start-ups provides an incentive to get students to focus on important societal themes. “Students,” he says, “are much more attracted to what’s happening around them than to, as they say, dead white men.”

One of Hazeltine’s current course offerings, “The Engineer’s Burden,” deals with the philosophy and ethics of technological innovation. “Do you need technology to change the world?” he asks. “The obvious answer is yes.” But there are important, deeper issues, such as “asking not just the question ‘How do you build a better mousetrap?’ but also ‘Should you build a better mousetrap?’”

The business world, Hazeltine insists, can be not a hindrance to important social change but a potential agent of it. “It’s easy to knock big business,” he says, “but social change has come through many of the things that companies and organizations have done.” One of his courses studies how adapting certain technologies has helped and served people in remote areas and developing countries. Having taught at the universities of Zambia, Malawi, and Botswana, as well as at Africa University in Zimbabwe, he’s particularly interested in Africa. His “Appropriate Technology” course gets liberal arts students actually building stuff and learning about how such things as aquaculture and simple applications for solar power can be useful in the developing world.

There’s always something new at the junction of technology and culture, and it’s this constant change that keeps Hazeltine fresh after all these decades. “It’s fun to keep up with it and think about it,” he says. And the case studies he uses in his classes are always changing—he replaces a third of them every semester. He swears that he really was going to retire back in 1997. He was going to travel, spend more time in the Adirondacks—stuff like that.

“But when it really got down to saying I wasn’t going to be coming in next week, that didn’t seem attractive at all,” he says. “I don’t play golf. Cleaning out the basement would be interesting for two to three days. I already travel.” For a while after he retired, Hazeltine says he was asked every year whether or not he would teach the next one.

“Now it just happens,” he says. “Nobody asks.”

Read more about the launch of the multidisciplinary center for entrepreneurship here.

Louise Sloan ’88 is the BAM’s deputy editor.