What do the Marx Brothers, the Internet, and Sean Kelly ’84 have in common?

Give up? They all share in the spirit of S. J. Perelman ’25, whose career as a humorist and New Yorker writer left an indelible mark on America’s funny bone.

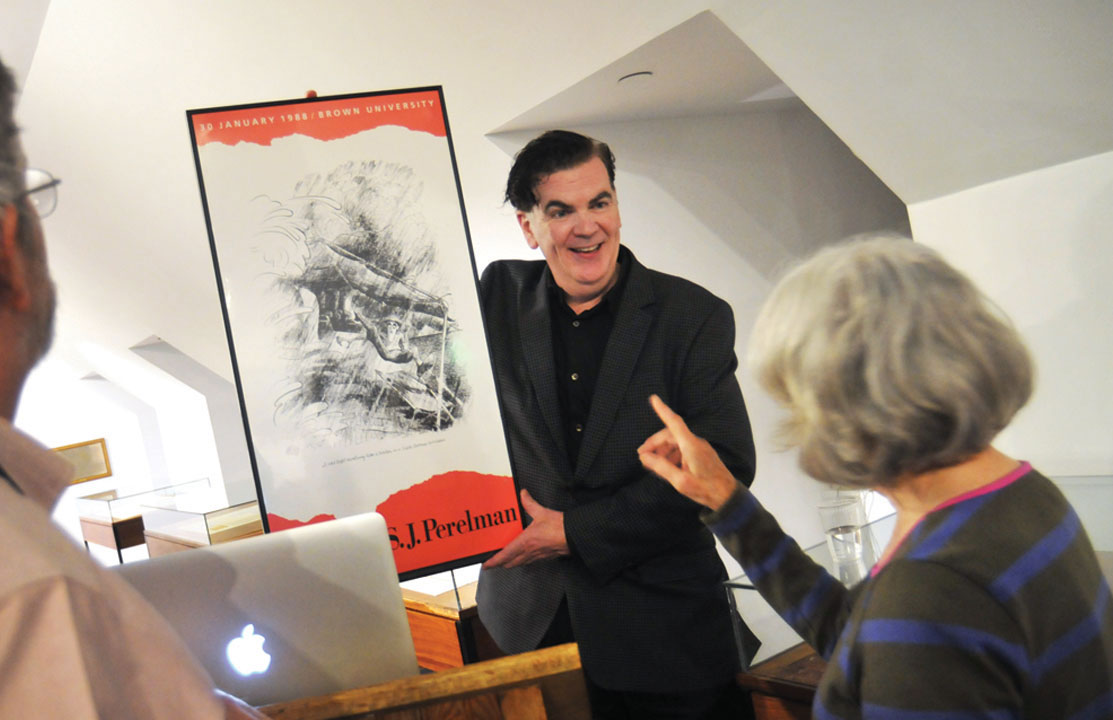

At least, this is how Kelly told it in his multimedia presentation, "The Sophisticated Silliness of S.J. Perelman ’25," at the John Hay Library in November. Like Perelman before him, Kelly is an award-winning cartoonist whose career started gaining traction while at Brown. In fact, Kelly might not have landed at Brown if it wasn't for Perelman—Kelly says he'd never heard of the school until he read a biography of Perelman.

Ironically, Perelman spent so much time writing for the campus humor magazine, the Brown Jug, that he never actually graduated. He may have been, as Kelly claims, “the greatest twentieth century comic,” but Perelman couldn’t pass trig. He redeemed himself with an honorary degree in 1965.

By that time, he’d graduated from cartoons to long-form written pieces. He’d even written screenplays for a few Marx Brothers movies. Kelly points to one of these movies, Horse Feathers, as Perelman’s satirical take on Ivy League brown-nosing. Perelman had made a name for himself as a cultural polyglot—someone who mixed Yiddish with Latin, puns with street slang, and high-minded poesy with low-brow punchlines.

People didn’t really get it at first. Tamar Katz, one of the English professors interviewed in Kelly’s presentation, says the New Yorker originally rejected Perelman’s work because, between the allusions and digressions and what seemed to be nonsense, “there was too much going on.” It was impossible to follow—absurd, even surreal. But, Kelly says, this was part of the fun. Perelman’s work lampooned the pretentiousness both of the New Yorker’s readers and of Perelman himself.

Thanks to a wealth of archival material left behind by the humorist’s family, Kelly had a window into Perelman’s creative process. He’d been a manic consumer of information, Kelly says, who curated bits of news from far and wide and “quite literally cut-and-pasted” them into absurd juxtapositions. Perelman inundated himself with information that was bizarre, even worthless—“It was essentially the Internet,” Kelly quips. But it was more than just a time suck. “He used these snippets as springboards, opportunities for wild adventures.”

The process of turning random ideas into art was often painstaking. Kelly recounted a story he’d heard about how Perelman was once in the middle of writing a sentence when the phone rang. He answered it and said, “I’ll call you back when I finish this sentence.” And he did—a full two days later. Kelly says such intensive labor is evident in “the richness of his wordplay and the complexity of his structure.”

But despite the sly critiques, the self-deprecation, and the obsessive work ethic that dominated Perelman’s career, Kelly says, what lingers is “a profound sense of joy.”