On a predictably humid south Florida morning last May, a couple of dozen men who pick tomatoes for a living took a break from their grueling work, sat down on a concrete wall, and listened. They had good reason to, for the lesson of the day was all about them.

Speaking in the men’s native Spanish, three former farm workers and two other staff members from an organization called the Coalition of Immokalee Workers (CIW) set about informing the tomato pickers of their rights. It’s important for them to know, the CIW educators explained, that, while working hard in hot fields, they are entitled to safe drinking water, toilets, and shade. They have the right to work away from pesticide sprayers and to get a fair wage for all the hours they put in. They should not have to face any physical or verbal abuse, and they have a right to leave the premises whenever they need to. Finally, they are entitled to report even the smallest complaint without fear of retribution.

What was extraordinary about the scene is that it has become commonplace. America’s farm workers have long been subject to brutal conditions and denied basic workplace rights. Conditions in Florida’s tomato industry were once so dismal that they inspired Edward R. Murrow’s 1960 documentary Harvest of Shame. Wage theft, beatings, and other abuses were common, and migrant workers who stuck up for themselves rightly feared retribution. Today, however, as the educators handed out pamphlets outlining the rights they’d just described and the phone numbers to call to report infractions—anonymously if the workers wished—a pickup truck idled, ready to haul a wheeled shade tent, two portable toilets and a hand-washing sink out to where they were working that day. No bosses paced nearby, anxious to get the crews out working again or nervous over the trouble all this rights talk could stir up. This uneventful scene, in fact, has been played out many times in recent years along Florida’s tomato belt. No organization has been more responsible for this change in farm worker conditions than the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. Based in the Florida farm community of Immokalee, home to a critical mass of tomato-field workers and about an hour inland from the gleaming beachfront developments along the Gulf of Mexico, CIW has in recent years attracted attention in some of the country’s and the world’s most rarefied offices, from the board rooms of giant corporations and high-profile nongovernmental organizations all the way to the White House.

CIW has been recognized by the Clinton Global Initiative, Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, the U.S. Department of State, and the United Nations. Kerry Kennedy ’81, president of Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights, which gave CIW its annual human rights award and which continues to act as a partner and adviser, called it a “pretty spectacular David and Goliath story … not only because of the extraordinary difficulty they’re up against, but also because of the incredible capacity of the CIW to actually create change.” Former President Bill Clinton has called CIW’s approach “brilliant,” and Jimmy Carter said he hoped it would be a model for the entire agriculture industry. Secretary of State John Kerry, who last year gave the group the Presidential Award for Extraordinary Efforts to Combat Trafficking in Persons, said CIW has “pioneered a zero tolerance policy that puts workers and social responsibility at the absolute center.”

Founded in 1993 when Greg Asbed ‘85 and Laura Germino ’84 teamed up with a small group of workers, the CIW was soon directing labor stoppages, hunger strikes, and 200-mile marches, all to draw attention to conditions in south Florida’s agricultural fields. The group focused on everything from ending a decline in worker wages to exposing the brute force some growers were using to keep workers on the job.

Although reforming conditions in south Florida fields back then was contentious and often dangerous work—90 percent of the country’s winter tomatoes are picked in south Florida, whose farms supply most of the country’s fast food chains, food service vendors, and grocery stores—it was not that different from the kind of advocacy that had been going on for decades. What has distinguished the CIW approach—and what has made it a particularly successful agent of change—is a more sophisticated, marketplace-centered strategy.

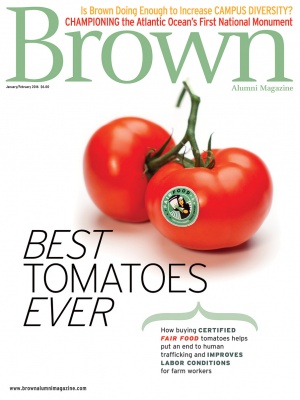

This strategy developed after Asbed, Germino, and other CIW leaders became frustrated that CIW’s traditional tactics were not producing the kind of wholesale improvement in workers’ lives they were seeking. Noting the periodic eruptions of bad press for American brands discovered to have profited from unsafe and unfair labor practices, especially in facilities located overseas. the group shifted its aim from the local farms to the big companies atop the supply chain. Given the public-relations benefit to major corporations like Walmart, the country’s largest grocer, to be able to claim that all their produce was picked by relatively well-treated farm workers, could the CIW set up a system to make the claim affordable and credible? If consumers were so eager to buy certified organic tomatoes, wouldn’t they feel even better about choosing certified fairly grown ones?

The result has been the Fair Food Program (FFP). The program begins with the idea that the end user, in this case the consumer, is likely to prefer tomatoes that have been credibly certified to have been picked and processed without any worker abuse, and that reputation-sensitive chains are eager to give the customer what he or she wants. That means companies like Walmart, which is now working with CIW to expand the group’s program to other tomato-growing states and to other crops, can no longer claim ignorance of what happens in the farm fields. Tomato growers who sell to companies in the program—including Taco Bell, McDonald’s, Burger King, Whole Foods, Trader Joe’s, and, as of last year, the parent company of the Giant and Stop & Shop grocery chains—must guarantee that workers are treated in line with the program’s requirements or lose their right to sell to these mega-buyers. No longer can farm-crew leaders lord it over workers with the impunity that prevailed for decades.

The FFP includes rigorous auditing overseen by former New York Judge Laura Safer Espinoza, who retired to Florida and who, after hearing news reports of slavery in the fields, volunteered to help. It relies on front-end education, health and safety committees on all participating farms, detailed interviews with workers during comprehensive audits covering field conditions, management and payroll practices, and an investigation process that can lead to a joint corrective action plan with the grower, or, if that fails, suspension from the program and loss of access to customers. An FFP approval label is used in some participating stores to let customers know their food was grown under closely monitored, humane conditions. Thanks to the Internet, customers also have an easier time learning about how the supply chain works and stepping up pressure to ensure better treatment of farm workers.

Another important element of the CIW approach is that farm workers are involved in every aspect of its work, from setting strategy to educating fellow workers. Many CIW employees came up through the fields and so have seen horrific conditions firsthand.

Over breakfast after the training session in May, education team members recounted how conditions used to be. One of them, Julia de la Cruz, said that before the Fair Food Program, wage theft, verbal abuse, and sexual harassment were rampant, and “you couldn’t speak up about anything” for fear of losing work. Bathrooms were filthy and often so far away that it was easier for workers to urinate and defecate in the nearby groves, and as for drinking water, well, “You don’t even want to talk about that,” she said.

Lupe Gonzalo, who wore a T-shirt reading “Is Your Food Fair?”, said that for women in the field, sexual harassment and sometimes violence were universal, “everybody, every day.” The first time she heard a CIW team speak, she recalled, “I saw that it was going to change,” and the prospect of “being given back your dignity” inspired her to get involved.

The role of workers in CIW has been key to its success, say Asbed and Germino. After all, farm workers have experienced life in the fields, and they know better than anyone what needs to change. In the old days, for example, growers would bus workers to the fields and then force them to wait, unpaid, until the dew dried from the crops. Now the FFP guarantees they are paid even during downtime, and it requires growers to use time clocks that can be checked by auditors.

“Only your lunch break can be deducted,” a CIW pamphlet distributed to all workers explains. “If you are waiting for the dew to dry from the plants, you’re on the clock (count it); if the truck is late and you have to wait for it, you’re on the clock. If it rains and you have to stop, but you do not go back home, you’re on the clock.”

Pay for tomato pickers is calculated per bucket, and in the past a “dumper” could refuse to accept a bucket as full unless it was “cupped,” or overflowing. The educational pamphlet likens that to “giving away work,” and includes a picture of what constitutes a full bucket. Susan Marquis, the author of a forthcoming book on CIW, points out that only people with experience working the fields could understand the significance of the definition of a full bucket. “Yet it’s something that was a major flash point for violence in the field,” says Marquis, who is dean of the Pardee RAND Graduate School, which is based at the RAND Corporation in California.

The FFP also calls for companies buying tomatoes to pay a penny-a-pound bonus. It’s an insignificant amount to consumers, but Asbed and Germino say it has boosted paychecks by fifty to seventy dollars a week. And if workers do see abuses in the fields, the pamphlet they receive from CIW includes a phone number for anonymous complaints that help CIW track the worst offenders.

“If you are working (or you know someone else who is working) for an employer who does not let you leave the camp or change employers,” the pamphlet reads, “hits you or threatens you, and who leaves you almost without pay because he says that you owe him, call the Anti-Slavery Office of the CIW immediately!”

Marquis says the FFP raises the ante for an industry that the government has failed to adequately regulate for almost a century. To gain political support from Southern Congressmen, New Dealers in the 1930s excluded farm workers from the program’s labor protections. Although there was some progress in the 1960s and 1970s, she says, enforcement has been lax. “It’s a migrant workforce,” she says. “They’re moving all the time, following the crops up the coast. So if you’re taking years [to investigate a complaint], the probability of that worker being around is not high.” The Fair Food Program, thanks to its worker education program, its grievance process, its extensive auditing, and the participation of workers themselves, forces quick action. If that doesn’t happen, she says, “then there are market sanctions.”

To hear Asbed and Germino tell it, they didn’t start out with a grand plan to develop a new paradigm now being studied by labor advocates in other industries, from Vermont dairy farming to Asian clothing manufacturing. Nor did they come up with some ambitious economic theory they wanted to test. Their goal was to solve the problems that the workers themselves identified. Despite their increasing fame, Asbed, Germino, and other CIW staffers still work in a modest one-story building that doubles as a community center, radio station, and rudimentary community store. The windows overlook the parking lot where workers load onto buses each morning. And they politely resist efforts by journalists to focus on them rather than their coworkers, even as they recognize that their backgrounds give them a better chance of being heard in the corridors of power.

Neither Asbed, a neurosciences concentrator, nor Germino, who studied history, was a stereotypical Brown campus activist, although Asbed traces his hunger for social justice back to his own lineage. His grandmother’s family was killed in the Armenian genocide, and his grandmother only survived, he says, because she was sold to Kurds at the age of thirteen. As for his father, Norig, Asbed says, “there’s no word for the type of poverty he was born into.” Norig Asbed, who died in October, found his way to the United States to study physics and engineering and eventually went to work for the defense department. Greg grew up in Rockville, Maryland, and originally planned to become a doctor, a researcher, or a teacher after Brown. He met Germino, who grew up in Charlottesville, Virginia, and worked as a writing fellow while at Brown, at an off-campus party. They married in 1993.

After graduation, Germino served with the Peace Corps in Africa. Asbed went to Haiti as part of the Providence-based Haitian Project (whose current president is Patrick Moynihan ’87) during a time of growing social unrest in the country, where he picked up organizing tactics from the peasants movement and, just as importantly, learned Haitian Creole. The language connection drew the couple to legal aid work in south Florida, where many workers in the tomato fields at the time spoke Creole. This allowed Asbed to help unite workers from Haiti and Spanish-speaking countries at a time when farm bosses were using language differences to pit workers against one another.

In Florida, Asbed and Germino went door to door to make sure workers knew their rights. They met Lucas Benitez, who became CIW’s cofounder and codirector, and who’d come to the United States from Mexico at seventeen “ready to work but not ready to receive really low wages and no respect,” he said through a translator at CIW’s headquarters last spring. Benitez described a world in which crew leaders yelled at workers and used barking dogs to intimidate them, where attempts to take a break or speak up about abuse could lead to word that “tomorrow, you don’t have work.” Benitez became good friends with Asbed and Germino, as well as partners in their organizing work. It helped that, while preparing to launch CIW, Asbed worked in the fields. “His diploma from Brown wasn’t enough,” Benitez joked.

The couple and their colleagues surveyed workers about their priorities. They organized a seven-day general strike against one area growing company that was trying to lower pay below the minimum wage. Marches and protests against buyers followed, all against a backdrop of abuses that ranged from the petty to the horrific. The tomato industry, with its migrant, largely foreign-born population, wasn’t just rife with exploitation, it was also a place where human trafficking flourished. It was, one U.S. Department of Justice official said, “ground zero for modern slavery.”

Behind closed doors workers were guarded at gunpoint, threatened, beaten, raped, denied access to telephones, or deprived of their pay. In one case, workers were locked and chained inside a U-Haul truck at night until one of them spotted a hole and managed to escape. The CIW would later secure the same model of truck and create an anti-slavery museum inside it.

Human trafficking became Germino’s specialty. She and her colleagues worked closely with local and federal authorities, using intelligence they’d gathered through CIW’s rapidly expanding network of contacts, and even some undercover work. Over the past fifteen years, Secretary of State Kerry said at the White House award ceremony, nine major investigations have freed more than 1,200 workers in the area from captivity. CIW played a key role in seven of them.

“The coalition has effectively eradicated human trafficking in the farms that participate in their Fair Food Program,” Kerry said. “That is an extraordinary accomplishment.”

Asbed, meanwhile, focused on organization and strategy. Discouraged that, despite CIW’s successes, abuses in the farm fields were still going on, he set out to zero in on why the problem persisted. The issue, he said, was deniability. Growers could simply claim they didn’t know what the crew bosses were doing. And companies buying the tomatoes could say they knew nothing about worker conditions, as it wasn’t their responsibility.

To change this, CIW first approached Taco Bell, which wanted nothing to do with it. CIW launched a four-year boycott, lining up partners, from students to religious groups, to ramp up pressure on the company, which finally came around. Other companies gradually followed suit after seeing the public-relations hit Taco Bell had taken. Conditions in the fields continued to improve. Susan Marquis says the relationship between CIW and growers has evolved over the past twenty years from “open warfare” to “quite collaborative.”

Craig Cogut ’75, a former Brown trustee and chairman of Pegasus Capital Advisors, is an enthusiastic backer of CIW. He describes its work as a model in tune with the times. “I think business is increasingly receptive to this,” says Cogut, who learned of CIW when his son Jonathan ’13 worked on Food Chains, a documentary about the group’s efforts. “They don’t like to be pushed. They like to be proactive.” At the same time, “there’s ready information available in the media, and corporations do care about image, particularly with millennials. Everything else being equal, they will come to brands they see as sensitive versus those they don’t.”

Not all food companies see the value of CIW’s work. Wendy’s, for example, is a longtime holdout, and among supermarkets, Florida mainstay Publix has refused to talk, despite years of requests, demonstrations, and pleas to ensure that their neighbors are treated with dignity.

Still, CIW’s success has spawned similar efforts in other states, including a group called Migrant Justice in Vermont, which is negotiating with Ben and Jerry’s on an FFP-like agreement for dairy workers. Like some of the boutique brands that have agreements with CIW, Ben and Jerry’s seems an obvious fit, says Brendan O’Neill, the development and campaign coordinator for Migrant Justice. Yet, he says, “there was a passivity” to their earliest conversations with the company until dairy farmers took their case to the public and to board members.

O’Neill says he and his colleagues had been following CIW’s work “as fans from afar,” particularly of its method for dealing with big, image-conscious brands. He called Germino’s work on slavery “tremendously inspiring,” and said she’s talked to the Vermont group’s members about similar situations and explained their options. O’Neill describes Asbed as a mentor and “a tremendous strategic thinker who never lost sight of his role, to be behind the scenes and to help build an organization. But it’s all about the workers. The workers need to be leading.”

Kerry Kennedy, whose father famously supported farm worker-rights activist Cesar Chavez in California, has joined CIW at demonstrations along with her mother, Ethel. She offered similarly effusive praise for Asbed and Germino. “I think they’re a reflection in some ways of Brown at its very best,” she says. “I think that Brown offers an extraordinary liberal arts education that attracts people who are interested in taking a creative twist in their career choices and their approach to the world.” As a parent of one Brown student and another who’ll matriculate next year, Kennedy adds, “I hope and pray they look at Greg and Laura and say to themselves, ‘This is what success looks like.’”

Asbed and Germino have their own, typically low key, yet brazenly ambitious idea of success. Rather than see their work celebrated, they dream of its becoming obsolete. As Germino put it at a White House session on human trafficking in 2013, success means not exposing abuse and bringing those responsible for it to justice—it means preventing it entirely. “Actual success,” she said, “would be getting to the point where that headline ‘Slavery in the Fields’ doesn’t happen—where the dog doesn’t bark. Where the headline is ‘No Slavery in the Fields.’ Not a compelling headline for the press, but so much more exciting.”

“Then you have a world without victims,” Asbed says. “That’s what this system achieves.”

Contributing Editor Stephanie Grace is a political columnist for the New Orleans Advocate.