If we mere mortals are lucky, we might—if we train really hard—run a marathon or two in our lifetimes. Or maybe a half-marathon. How about a 10k?

And then there’s the relatively unknown ultramarathon. To put it in perspective, an average marathoner takes between three and six hours to finish. To get through the Ironman Triathlon World Championship in Kona, Hawaii, you need eight to sixteen hours. The Western States 100 Endurance Run, whose course winds partly through a California wilderness, takes between fifteen and thirty hours to complete.

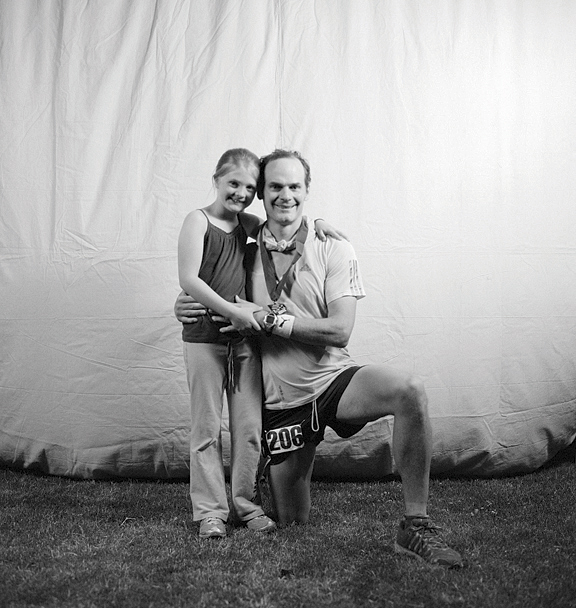

Who would even attempt such a grueling, physically demanding sport? Meet Karl Hoagland ’87, a former Goldman Sachs investment banker and hotel entrepreneur. Hoagland grew up in the Midwest playing baseball and soccer, and, after he chose Brown over Stanford, he played both sports for the Bears. After graduation, he continued to play soccer in a competitive league, but thirteen years ago, at the age of thirty-eight, he blew out his knee by tearing his ACL, MCL, and meniscus. While working to get back in shape, he attended a New Year’s Eve party at which a friend challenged him to run a marathon. He took the challenge.

“I had never run distance before, so a marathon was pretty audacious,” he says. About two months later, in early 2003, Hoagland completed the Napa Valley Marathon in just over four hours. (He lives in Fairfax, California, near San Francisco.) “The last six miles were incredibly painful and arduous,” Hoagland recalls, “but once I crossed the finish line I had such a great feeling. I started thinking, ‘I love this and maybe I could even do better.’ I was really drawn to it.”

Distance running has never been more popular in the United States. More than two million runners compete in half-marathons every year, and more than half a million finish marathons. For the rare few who find running 26.2 miles a bit of a bore, the next frontier is the ultramarathon. Although there is no one ultramarathon distance—anything longer than a marathon can be considered an ultramarathon—the most common events are fifty kilometers (about thirty-one miles), 100 kilometers (a little more than sixty-two miles), fifty miles, and 100 miles. Some ultramarathons are also timed events won by whoever runs the most distance in six, twelve, twenty-four, or forty-eight hours.

As Hoagland continued to train, he began running with friends who were a subspecies of ultramarathoners who ran on trails. “I liked trail running even more [than marathons],” he says. “Up and down hills made it a lot more interesting.” In November 2003 he completed the Quad Dipsea, a hilly 28.4-mile race along the Dipsea Trail near Mill Valley, California.

Not only did Hoagland love the competition, he thrived. A few months after the Quad Dipsea, in early 2004, he competed in his first fifty-mile race, the Jed Smith Ultra Classic, named after early-nineteenth-century mountain man Jedediah Smith. At the age of thirty-nine, he finished in eight hours, thirty-five minutes, and fifty-six seconds, good enough for eighth place.

Next up was the Western States 100 Endurance Run, which begins in Squaw Valley, California, and ends in Auburn, northeast of Sacramento. The Western States 100 bills itself as “the oldest and most prestigious 100-mile trail race.” It includes a climb of more than 18,000 feet and a descent of nearly 23,000 feet. “It seemed to be my destiny,” Hoagland says, “to do the Western States 100.”

In June of 2005, Hoagland finished the race in twenty-two hours, forty-nine minutes, and nineteen seconds, earning a silver buckle for a time of under twenty-four hours. For most people—you might even say for most sane people—that would be the pinnacle of an ultramarathoning career that could now continue with less challenging courses.

But not Hoagland. “I was going to let it go and not do it again,” he says, “but I wanted to see what would happen if I really trained to race it instead of just complete it. I wanted to see if I could go under twenty hours.”

He returned to the Western States 100 in 2009—it took four years for him to get through in the qualifying lottery—and finished sixteenth, posting a time of nineteen hours, forty-one minutes, and twenty-two seconds. The following year, he was fourteenth, with a time of eighteen hours, sixteen minutes, and twenty-six seconds. In 2011, he finished twenty-first, despite his personal-record time of eighteen hours, fifteen minutes, and forty-eight seconds.

The faster time, Hoagland says, was due to a bear encounter at mile ninety-eight: “A mama bear and I had a showdown. The bear ran up a tree, but I had such a shot of adrenaline that I just sprinted in for the last mile.”

He also completed the race in 2012, 2014, and 2015, earning a silver buckle every time he’s competed. Including the Western States 100, Hoagland has completed fifty-five ultra races over the past twelve years. He has also run several marathons, including four New York City Marathons. In 2006, he finished that race in 2:59, a personal best marathon time.

Hoagland is now fifty years old, and although he plans to keep competing, he concentrates more on other parts of his life now, including his three children. “I am going to keep doing it,” he says, “but I am getting a lot out of just completing the distances and being part of the races, instead of trying to race them for my fastest time possible.”

In 2013, Hoagland bought UltraRunning magazine. “I like new challenges,” he says. “I am kind of a serial obsessionist.” The magazine has become a way “for me to participate in the sport and give back to the sport, and help the sport grow, and help other people be successful and enjoy it.”

He’s also started playing baseball again and will travel with his team to Cuba in February. “It should be a really fun cultural experience,” Hoagland says. He also coaches his son in the sport. “With me playing and him playing,” he says, “it is something we share that’s fun.”