Ayad Akhtar ‘93 wanted to become a great American writer. By the time

he graduated from Brown, he had read the American classics—Hawthorne,

Melville, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald. He was also steeped in such

modernist European masters as Proust, Robert Musil, Kafka, and Rilke.

But it was the Jewish novelists of the second half of the twentieth

century—Bellow, Roth, and Potok among them—that Akhtar particularly

admired.

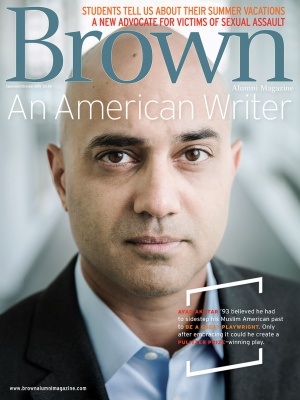

Photo: Jared Castaldi

By the time Akhtar was in his early thirties, he’d finished a novel about a poet who worked on Wall Street. Its structure and tone were heavily influenced by the work of Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa, who wrote aphoristic, nonlinear novels full of extended ruminations on existence, love, death, and the meaning of life. Akhtar hoped his work would do honor to Pessoa. There was one small problem. According to Akhtar, the novel was “god-awful.” It showed a limited knowledge of craft. The storyline was convoluted. And it certainly wasn’t entertaining.

Then, in the early 2000s, Akhtar had a revelation. “I was running from my culture,” he says. “My past, who I was.” He’d grown up in suburban Milwaukee, the child of Pakistani immigrants who were both doctors. Although he wasn’t raised to be religious, as a child he was surrounded by Muslims.

And so Akhtar wrote about Muslim Americans. He chronicled the strains in their family relations, their debates about religion and assimilation, the cruelty inflicted on women in the name of Allah, and the struggle in the face of American commercialism to retain the richness of Islamic culture. He also cast his gaze abroad, writing about America’s confrontation with Islam.

He followed the old adage, write what you know. Within a few years, he’d completed three New York–produced plays as well as the acclaimed novel American Dervish. And he’d won a Pulitzer Prize.

When I met Akhtar last winter, he looked tired. Over the previous six months, he’d had three plays open in New York City: The Who & The What, The Invisible Hand, and Disgraced, which opened at Lincoln Center in 2012, won the Pulitzer for drama a year later, and then moved to Broadway last year. At Brown he’d focused on acting, and in 2011 he played Neel Kashkari, assistant secretary of the U.S. treasury for international economics and development, in HBO’s Too Big to Fail, which focused on the 2008 financial crisis.

“I find myself exhausted,” he says. He was rewriting all three plays throughout rehearsals, sometimes until the day before opening night. Now he was rewriting an adaptation of Disgraced for television. “I’ve been facing audiences, which is always a joy,” he says, “but facing critics, which is never a joy.” Then he catches himself. Of course, he says, these are “high-class problems.”

In conversation, he often pauses and then makes pronouncements that can sound academic but that reflect a deep analytical mind and a fierce intelligence. When I asked him if his work was autobiographical, he said: “By answering in the affirmative, I undermine the truth value of the fictive creation through biographical facts. By answering in the negative, I undermine the authenticity of the fictive creation by saying I deny that experience. In both cases, it’s a dead end.”

Ask friends or colleagues about Akhtar and the first thing they will tell you is that he’s intense. “I don’t know anyone who can work so hard with such discipline and productivity,” says Michael Pollard, a longtime friend who is a TV executive at the Disney-ABC Television group. Amanda Watkins, a theater producer who shepherded Disgraced to Broadway, says Akhtar rewrites constantly: “It’s hard to know how the guy has time for a personal life.” (He did marry, though the marriage ended in divorce.) Elise Joffe ’93, another longtime friend, describes his “fierce gaze and bright eyes.” When he directed her in a play at Brown, she says, “he wanted to be rehearsing all day, every day. There was nothing more important in the world.”

Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

Akhtar's play Disgraced debuted at Lincoln Center in 2012. Asif

Mandvi's character is a successful corporate lawyer until his Muslim

identity comes under question. On top of the world, he plummets to its

depths when he commits an unconscionable act against his wife, played

by Heidi Armbruster. The play exposes the tribalism that undergirds our

ethic and religious identities.

John Emigh, a professor emeritus of theater and performance studies who taught Akhtar, offers even greater praise. He compares the reception of Disgraced to Edward Albee’s breakthrough work, The Zoo Story: “I haven’t seen an audience respond to a play like that in fifty years.” The audience at the performance he attended, he says, felt a profound shock and discomfort during the play’s catharsis.

The structure of Disgraced is classic Aristotle—a hidden flaw in the hero leads to his downfall and an unbearable awareness of his true nature. It also bears a similarity to Shakespeare’s Othello. Each outsider—a Moor in Shakespeare and a Muslim American in Disgraced—breaks from his heritage to marry a white woman. Instead of assimilating as they hope, they revert to an ugly deformation of their past selves and destroy the thing they love most.

The success of Disgraced turned Akhtar into a spokesman, at least on the literary front, for Muslim America, sought out by the media for authentic insight into Islam and the Muslim immigrant experience. It’s not a role he wanted or embraces. He’s a writer, first and foremost, he says, his goal only to depict Muslim Americans honestly, which can sometimes mean exposing their flaws and prejudices. “I’m not interested in creating work that is a public relations gesture on the part of Muslim Americans,” he says.

The characters in his plays and novel, especially the men, are roiled by self-hatred. They regard Islam with derision and repugnance. They don’t even want to be seen with other Muslims or Pakistanis. One of Akhtar’s influences, Philip Roth, wrote about a similar ambivalence among Jews about their own culture.

Akhtar won’t say what he thought about 9/11. Doing so, he believes, would prejudice the audiences at his plays. Similarly, Akhtar also refuses to discuss his politics. The message his audience chooses to draw from his work, he says, is up to them: “Muslims can see Disgraced as a cautionary tale about the perils of Western civilization. Others could see it as confirmation of the idea that Muslims are savages. It leaves you the freedom to think whatever you want.”

Akhtar entered Brown as a sophomore, transferring after an unhappy time at the University of Rochester. He was drawn to theater, though at this stage he wanted to be an actor. On the first day of a theater class taught by Lowry Marshall, he showed up in a billowing white shirt and French designer white pants. He didn’t think he looked out of the ordinary, but his outfit drew attention. “We were all instantly smitten,” says Joffe. “He seemed so romantic.”

Joffe remembers Akhtar as a “deep thinker, passionate, brooding, pondering the nature of everything.” She says they discussed God. “Despite my being Jewish and his being Muslim, we were both grateful that our religions gave us an intimate doorway to our spiritual selves.”

Akhtar majored in theater arts and performed in plays by Shaw, Mamet, Shepard, and Shakespeare, all of whom came to influence his writing. He directed Joffe, now a Brooklyn psychotherapist and still a close friend, in a production of Jean Genet’s The Maids. Joffe says Akhtar was especially good with actors. “He has a real gift for seeing things in people that they can’t see in themselves,” she says. “It was almost like he was psychic.”

John Emigh, the professor who mentored Akhtar, remembers his former student’s “razor-sharp intelligence,” which could be both an asset and a detriment. Akhtar sometimes over-thought his roles, which could seem artificial. Emigh worked with him to get in touch with his emotional core. “He needed to trust his instincts,” Emigh says. In the end, Emigh says, Akhtar overcame his cerebral inclinations and emerged as an excellent actor.

The early 1990s were a time of identity politics on American campuses, but for the most part Akhtar eschewed them. He didn’t join any Muslim student groups. Joffe says she can’t remember him talking at all about ethnicity or religion. “It was not so important to him,” she says. Like many children of immigrants, he wanted to break with his past and assimilate. “I was pursuing the great American dream,” Akhtar says. “I could be whoever I wanted to be.”

After graduation, Akhtar went to Europe to study with the famed avant-garde Polish theatrical director Jerzy Grotowski. When he returned to New York City and began his nonstop writing, he assumed no one would be interested in his Muslim and Pakistani heritage. Akhtar’s twenties were a period of spiritual searching. He read about Buddhism, Hinduism, and mysticism. Joffe says he introduced her to Kabbalah. He was soaking up ideas, she says: “Everything has an influence on Ayad. He’s a huge receptacle.”

By the time Akhtar finally began writing about his past, America had become very much interested in learning and hearing more about Muslims, and to be a Muslim in America meant being singled out at the airport, stopped by police, and subjected to harassment. It became much harder to ignore his Muslim heritage. Akhtar himself did not have any run-ins with authorities, but he knew Muslims who did. In Disgraced, the Muslim character says he always invites the security guards to search him whenever he flies even if they haven’t asked.

It was also around this time that Akhtar’s marriage fell apart. “It was a devastating experience, one that led him to reexamine his life,” Joffe says. But she says it spurred a new commitment to his writing. “He poured himself even more into his work,” she says, “and used it as a way to further explore his identity, his relationship to his family, and to Islam.”

His friend Michael Pollard remembers Akhtar returning from a fishing trip with his father around this time. Akhtar carried a picture of his father looking hip and distinguished in Ray-Ban sunglasses. He was also bald. For years, Akhtar had used Rogaine and insisted barbers leave the little that was left of his hair.

Photo: Jared Castaldi

In February, Akhtar was invited to give a talk at TEDxBroadway. TEDx events are an offshoot of the famed TED Conferences and sponsored by local organizations or businesses rather than by TED’s national headquarters.

The mood, as is common at TEDx events, was upbeat and inspirational. The theme of the day was “What is the best Broadway can be?” and featured such talks as “Following Your Life’s Path, Not Your Life’s Plan” and “Turning (Very) Bad into Good.”

The first speech of the day, delivered by theatrical producer and Broadway investor Elliott Masie, was about marketing and big data. Technology could transform theater, Masie argued. Soon, a potential audience member might walk by a show and receive an offer for discount tickets on her Apple Watch. Or, said Masie, people could relay an instant digital message to box offices around Times Square saying they were interested in seeing a show. The theaters would then send them special reduced-price offers. Essentially, theaters would be bidding against one another for customers.

Masie, who now works mainly as a business analyst, speaker, and writer in Florida, wore an orange Izod shirt, purple blazer, and sneakers with orange shoelaces. He used slides. He also brought along a Catchbox, a microphone in a padded cube that audience members could toss to anyone who wanted to participate in the discussion. Masie urged the crowd to embrace his vision of the future of the theater. The audience responded warmly.

Akhtar came next. He hadn’t brought along a PowerPoint. He used a music stand as his podium. “We are living in an era of what we would call industrial storytelling,” he said, “by which I mean storytelling at the service of an increasingly synchronized global marketplace.” As for the influence of technology, he said it was subjecting individuals to “the regime of the image,” showing them ever more graphic images of “body, blood, and beauty.” It had turned stories into commodities.

At least in its ideal form, theater was different. It was “not easy to consume.” It could bring people together to experience the tragic nature of human experience, connecting the audience to something primordial, Dionysian. At the end of a great play, he maintained, the spectators quake with Aristotelian pity and terror, “a depth of emotion commensurate with our vulnerability to existence itself” in an experience “verging on religious awe.”

When Akhtar was done, the audience, many of whom were thirty-somethings working on the commercial side of theater, clapped politely. You’d be hard pressed to find any evidence of Akhtar’s vision of theater in the splashy, whiz-bang Broadway just outside the building.

HBO recently announced it would produce a version of Disgraced. Akhtar is also working on a new play and pitching a new TV show to the network about a family business dealing with the pressures of globalization.

After his speech at TEDx, Akhtar hung out in the lobby. One woman came up to him and said how much she liked his presentation. Later he said he wasn’t particularly concerned about the reception. “All I can be is myself,” he said.

So far, his strategy is working.