Born in Mexico City near the former home of the celebrated artist Frida Kahlo, Adriana Zavala ’96 AM, ’01 PhD, moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, as an infant. Though her family visited Mexico often during her childhood, she hadn’t been back for about ten years when she made a trip in the summer of 1993. “I realized that this was my destiny,” she says.

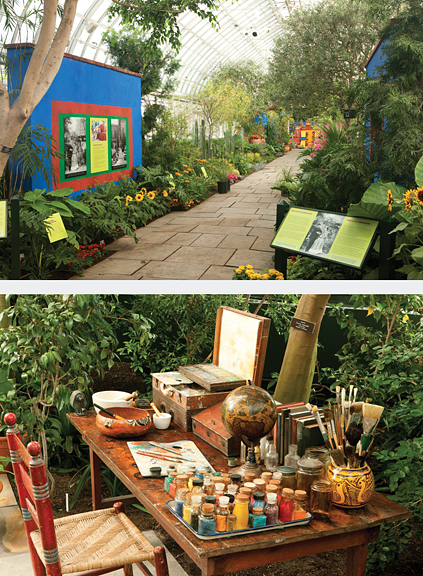

Installations in the Enid A. Haupt Conservatory are inspired by Casa Azul, Kahlo’s studio and garden in Mexico City’s Coyoacán neighborhood, which is now a museum. At the New York Botanical Garden, ceiling fans rotate high above a tree-filled greenhouse space bordered by walls painted in the Casa’s famous indigo blue. In the center of the greenhouse is a structure inspired by the four-sided pyramid on which Kahlo and her husband, Diego Rivera, placed pre-Columbian artifacts among cacti and other succulents.

A gallery in the nearby LuEsther T. Mertz Library displays paintings and drawings by Kahlo, including four remarkable still lifes, two stunning oils—the 1931 Portrait of Luther Burbank and the 1939 Two Nudes in the Forest—and the iconic image Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird of 1940, all of which illustrate the visual and symbolic importance for Kahlo of flowers, fruits, plants, roots, and trees. “She imbued plant imagery with cultural, spiritual, and personal meanings in unexpected ways,” Zavala notes.

A member of the Tufts faculty since 2001, Zavala sees herself as part of the first generation of scholars to offer a feminist critique of Mexican art history. Her dissertation, on images of indigenous women in twentieth-century Mexican art, won the Marie J. Langlois Prize for the outstanding dissertation in feminist studies.

“My life is about being an ambassador for the country where I was born,” Zavala says.

She first came to Brown to work in the Rockefeller Library’s bindery and collections-management department. When she entered the PhD program, Zavala was several years older than her fellow students. “I didn’t feel myself to be a natural fit at Brown,” she says. “They took a chance on me.”

Having earned her undergraduate degree from a large state school, the University of Cincinnati, she says she was “blown away” by the intellectual richness of the Brown community, where her mentors were the late art historian Kermit Champa and historian R. Douglas Cope.

Of her work in the Bronx, Zavala says, “I could not have dreamed up

a more interdisciplinary project, and that’s something I learned at

Brown.”